Life Cycles with Betty Kuntiwa Pumani

The paintings of Betty Kuntiwa Pumani form a part of a larger, living archive on Antaṟa, her mother’s Country. More than maps, they speak to ancestral songlines, place and ceremony.

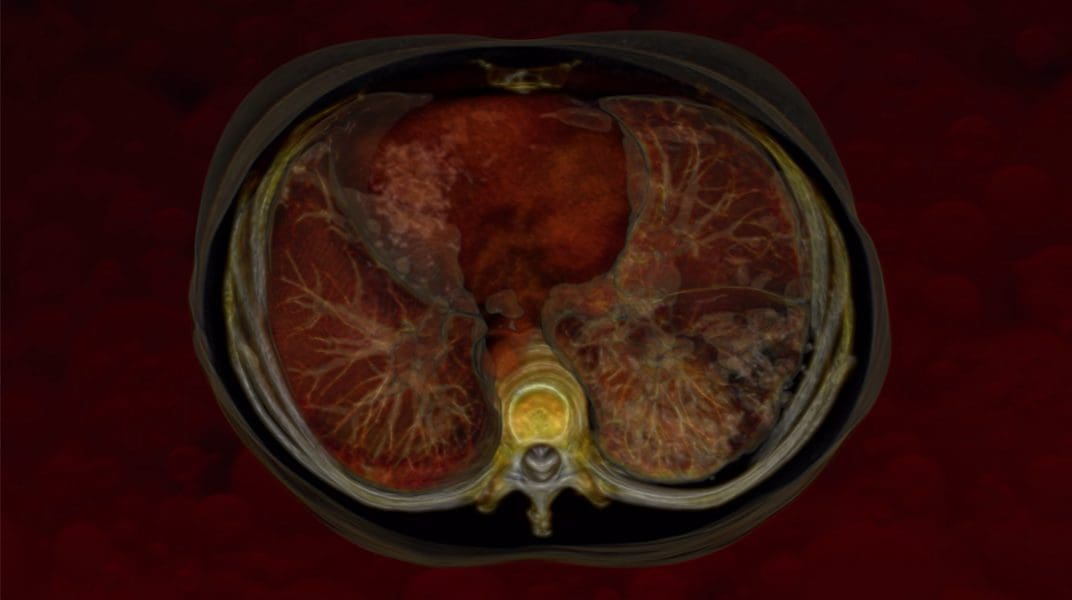

Karen Casey, Transplanted, video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Karen Casey, Transplanted, video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Karen Casey, Transmutation. Image courtesy of the artist.

Amy Karle, Bringing Bones to Life, 2016, video.

Patricia Piccinini, Teenage Metamorphosis, 2017, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, found objects.

Pia Interlandi, Living Death Mask, 2012. Photograph by Devika Bilimoria.

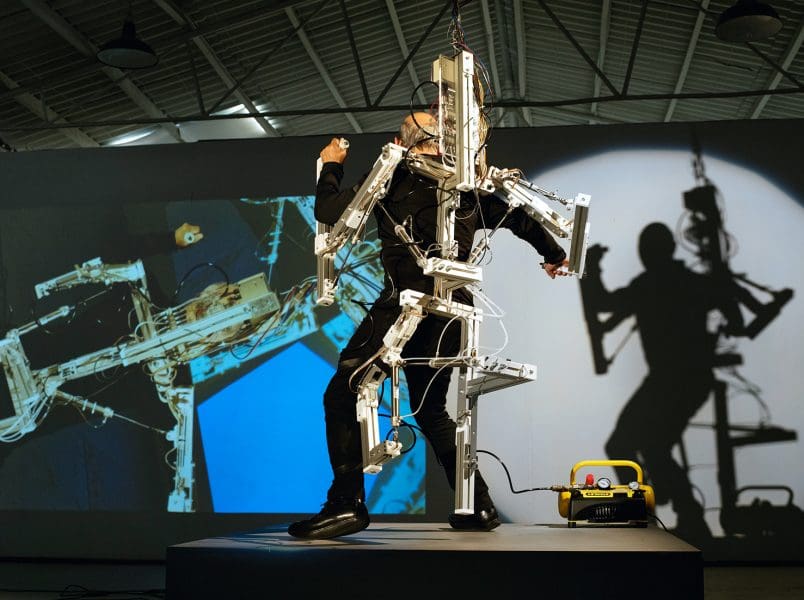

Stelarc, StickMan, 2017, aluminium, pneumatics, electronics. Photo Toni Wilkinson.

It is no exaggeration to say that Future U at RMIT Gallery addresses one of the most pivotal questions of our tumultuous present day. The intersection of humanity with technology is an incendiary subject that will, surely, only become more complex and perilous as history unfolds, particularly in the wake of such existential threats as the climate crisis and Covid-19. And as the works in Future U show, this technological acceleration is as frightening as it is exciting.

Curators Professor Jonathon Duckworth and Dr Evelyn Tsitas have assembled a selection of works, crossing multiple formats and mediums, that playfully, poetically and sometimes disturbingly explore how technology might affect our identity as humans, and indeed what constitutes being human. Artists include those with a global profile such as Patricia Piccinini, Stelarc and Bettina von Arnim, as well as some of Australia’s most innovative contemporary artists who deal with such topics, including Alexi Freeman, Jack Elwes, Amy Karle and Karen Casey, among others.

Some works examine how artificial intelligence (AI), machines and robotics have fundamentally altered how we define what it is to be human; others explore how technology has affected our relationship with environment and place; others still grapple with how the physical form of the human body can be augmented and recalibrated by machines – and the ethical implications of this.

An artist whose work might fit the latter category is Hobart-born, Melbourne-based Casey. Among her contributions to Future U is the remarkable video work Transplanted, 2021, created with medical imaging software. This animation converts scans of Casey’s body, taken for her own organ transplant, into hypnotising imagery that ‘maps’ the landscape of the artist’s organs, muscles, sinews and skeleton. And landscape is an appropriate word: this otherworldly video piece presents patterns that resemble river deltas or topography. At other times it resembles a Rorschach blot, or ink spill.

“I requested all my medical image files from the hospital and discovered by accident that I could open the software program and with some experimentation, transform my CT and MRI files into artworks,” says Casey. An earlier version of Transplanted was shown as part of Unhallowed Arts in Perth in 2018, which celebrated the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein. “Seeing as I carried someone else’s body part, that seemed somehow fitting.”

Transplanted also features an evocative soundscape designed by Nick Livingston, which, Casey explains, “contributes to the visual narrative through audio effects, created mostly from manipulated hospital and medical equipment sounds. The voice-over contextualises the work in relation to the physical and psychological challenges I experienced during that period.”

Casey, whose career as an artist began in the 1980s, says that Transplanted marks a certain departure from the rest of her oeuvre to date in its intense personal focus. However, the nature of much of her practice and output over the years makes her a good fit for the Future U exhibition. “I have been working within the liminal space between art, science and technology on-and-off for close to two decades now,” she says. Casey is also the founder and artistic director of Global Mind Project, an initiative that has created and presented art and performances based on neuroscience and brainwaves. Another of Casey’s works in Future U, Transmutation, 2021 is a Duratran print created from a CT scan of Casey’s head, and “represents a transitioning, of sorts, from human to cyborg.”

It should be noted that while many works in Future U consider the potentially dystopian and destructive ways that technology might transform humanity, for Casey it is very much a double-edged sword. While on one hand she acknowledges that her work “to some extent touches on moral and ethical issues,” the fact is that medical technology has ensured her survival and health. “The work is in a sense an homage to my donor and the amazing liver transplant team at Austin Hospital,” she says.

The creation of Transplanted was also, perhaps above all else, a process of coming to terms with the physical and emotional challenges of an organ transplant.

“It was purely curiosity that led me to more closely examine my own body and I think, like most artists, when presented with a large amount of potential creative material one tends to get inspired. The decision to take it further was perhaps driven by the realisation that it was necessary in order to close a chapter on a difficult and traumatic period of my life.

“It was actually quite confronting looking at some of those images and observing first-hand the degree of physical damage and trauma inflicted on my body … It has taken some time and courage to get beyond my personal discomfort at publicly displaying my damaged and distended body, and to be able to look at this work as just art.”

Future U

RMIT Gallery

29 July – 23 October