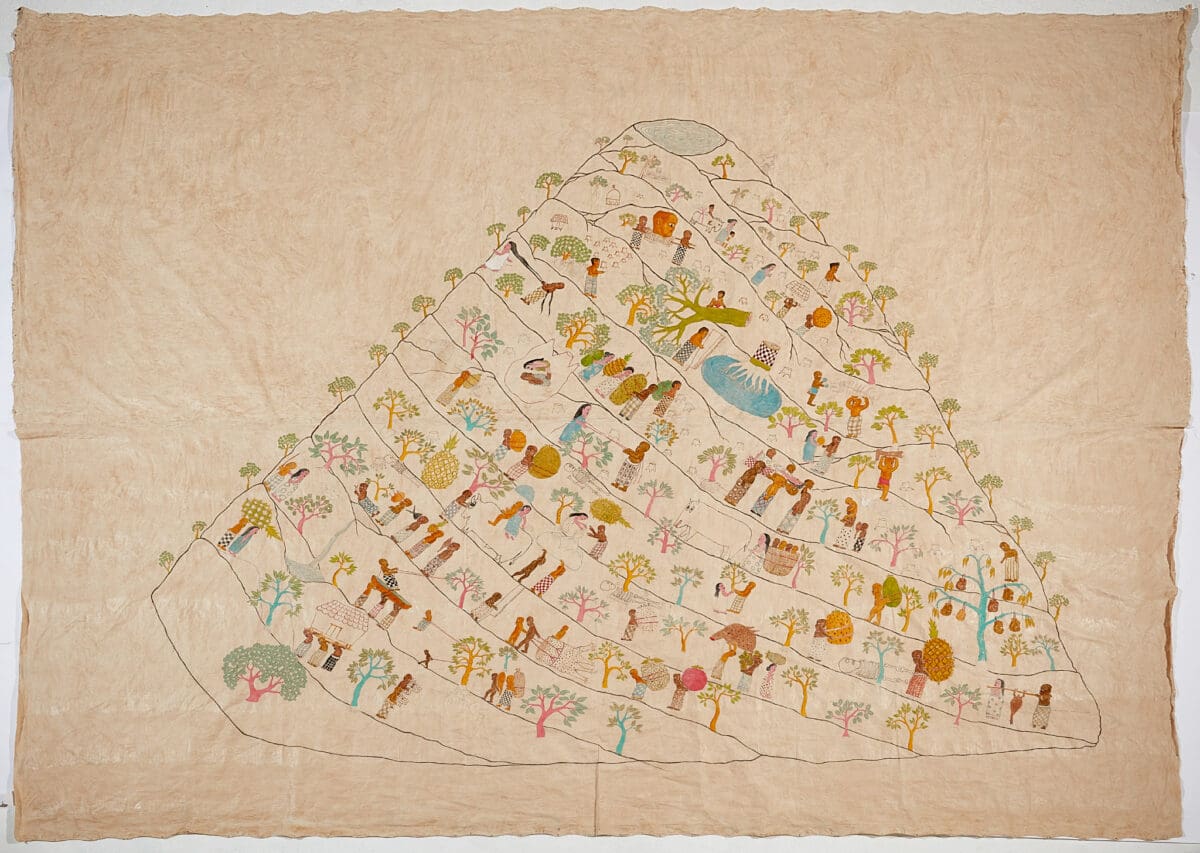

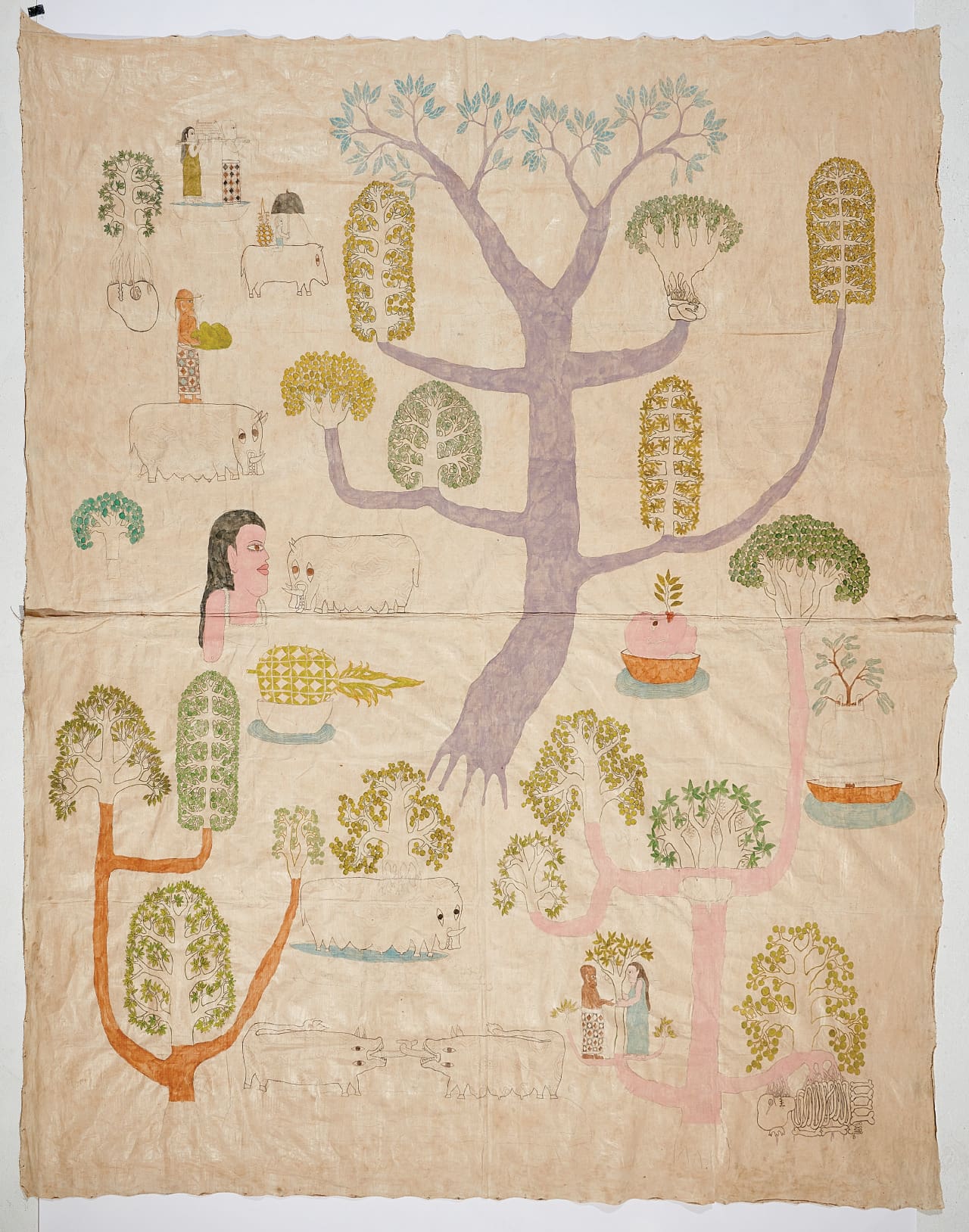

The artist Jumaadi paints and draws on the tough hide from water buffalo once used to plough rice fields. His art, which depicts Javanese folk culture, also encompasses cloth canvas, laboriously stretched and sealed in a large pond of rice glue, hand pressed like a silk screen.

The studio Jumaadi has kept in Imogiri in Yogyakarta for the past 11 years is surrounded by a beautiful dry landscape, contrasting with tropical expectations of Indonesia. It reminds him of his adopted second home in Australia, where he maintains a studio in the northern Sydney suburb of Brookvale. “That familiarity gave me that comfort of drying trees in the summer,” says the quietly spoken 51-year-old.

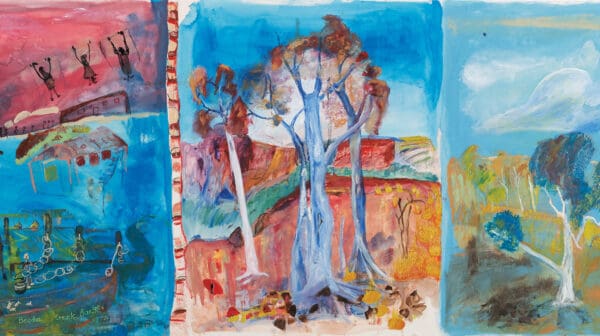

We are talking outside Bundanon Art Museum, inland from the New South Wales south coast, where Jumaadi recently completed a four-week residency in verdant, hilly countryside by the Shoalhaven River, with fellow artists, kangaroos and wombats as companions.

He is performing a shadow puppetry work here, The Sea is Still A Mystery, as part of the exhibition Tales of Land and Sea. With the sounds of sweet folk music and a soundscape of splashing, human calls and bird songs, he projects onto the wall a diptych of his paper cut-outs. These relay images of fishermen, sea creatures, an Arabian ship that sank east of Sumatra in the 9th century, and the fallout from later Portuguese and Dutch colonisation, including the salvaging of severed body parts. It’s the “colonial body in relation to violence”, as he puts it.

Jumaadi’s name comes from “two different thresholds of words, so different origin all together, but melded in Java”. Juma is Arabic, meaning Friday, the day he was born, and “adi” is Sanskrit, meaning good: his father wanted him to become a good person.

In the 1950s and early 60s, Jumaadi says, most of the arts in Indonesia were associated with the communists. Somehow, his father—a dancer— survived the massive slaughter wrought across the country by a military coup in 1965. Jumaadi’s father witnessed the violent disbandment of the largest non-ruling communist party in the world, the Partai Komunis Indonesia.

During this time, artists would be constantly questioned about their art making. “Art is dangerous,” they would be warned. Jumaadi laughs, ruefully: “You were in danger.”

The artist was born in 1973 in the densely populated city of Sidoarjo in East Java, where he still maintains a studio because he has many family members there, some 350 kilometres north-east of tranquil Imogiri. Growing up, he gradually pieced together the displacement that had brought his family to Sidoarjo: his grandmother’s village had been bombed during the civil war of the late 1940s, before Indonesian nationalist forces finally pushed past Dutch colonial rule in 1949.

Earlier traumas, such as the mass jailings in the 1920s following the communist-led revolt, likewise figure in Juamaadi’s art, but these moments also suggest universal suffering: “The history in the 20th century, especially that conflict of the colonial and the communist movement, in a lot of my work, history plays a big part as a starting point—then as a reflection, a reference, it helps me objectively to investigate the human condition,” he says.

“Personally, I don’t compare [others’] suffering with mine, but then I guess [the art] gets closer to the origin of suffering: spirituality. It is more investigating than suggesting conclusions.”

Jumaadi came to Sydney in 1997 because his then-girlfriend was Australian. After a year of photography training, with an eye to a career in photojournalism, he discovered photographic and visual art, which he then studied at the National School of Art at the former colonial Darlinghurst jail.

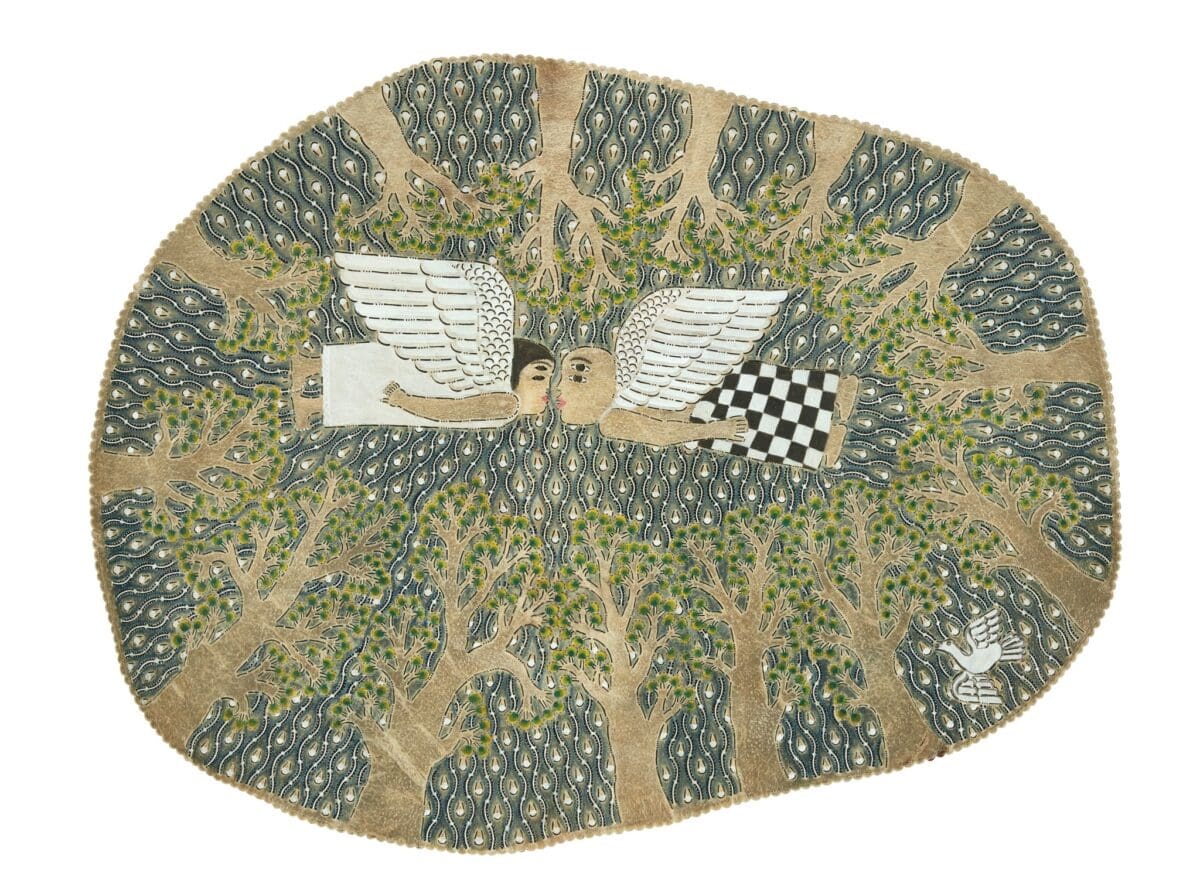

His work often depicts dual human figures, perhaps saying hello or goodbye, as well as motifs of wedding dresses and babies, “two different things posed together to create different meanings”, he says. “This is about birth, and death, and in-between. The nuances coming out of it are much more involved than what is present. So, I am not conscious to the message.”

Yet some works displayed at Bundanon strike this viewer as specific, such as his cloth painting work Flying artist from 2021, for example. One questions: is that Jumaadi himself flying beneath the wing over an archipelago of volcano islands, and are those migrants we can see through the plane’s windows?

Jumaadi says he was thinking of the “danger of dogma” when painting that work, of poor people selling land to make the annual Muslim pilgrimage, the Hajj to Mecca.

“The artist is actually outside the aeroplane, and carrying the aeroplane, but who is carrying who is always my interest,” he reflects. “You’re usually inside the world, rather than the world inside you—but mythology can be inside you.”

Tales of Land and Sea

Bundanon Art Museum (Shoalhaven/Jerrinja and Wandi Wandian Country NSW)

On now—16 June

This article was originally published in the May/June 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.