Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

From early beginnings as a political protestor and art photographer in the 1970s, Julie Rrap has maintained a multi-disciplinary art practice with solid foundations in performance art, photography and video. Creating work with a focus on historical and feminist representations of the female body, throughout her career Rrap has exhibited extensively throughout Europe and Australia, with major survey exhibitions instigated by the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. Here Rrap speaks about revisiting a collection of images initially created in Paris in the 1980s and how they have inspired a new video work three decades later.

Briony Downes: What was your path to art?

Julie Rrap: My path to art was a bit unorthodox. I only went to Art School briefly but because I was often helping my brother Mike Parr with his performances, I really got introduced to art through that connection. During my time studying for a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Queensland I was also influenced by politics and feminism. I was there at the height of the Vietnam War between 1969 to 1971. Women’s liberation coincided with that political period before it later morphed into feminism. I was very active in the “rad” movement and constantly marching in demonstrations.

In the 1970s I joined a performance workshop at The Tin Sheds which was part of the University of Sydney School of Architecture. I also worked as a photographer running a business with a colleague. We specialised in photographing art works for books and magazines, so my photo skills were acquired through producing professional quality work for publication and my conceptual interests were developed through my association with other artists interested in pushing the boundaries of art.

BD: You often refer to yourself as a trickster or a thief when it comes to making art. How does this way of being relate to your work and the concepts behind it?

JR: I began using the term trickster after making the images for Thief’s Journal in the 1980s. In this work I used Jean Genet’s book of the same name in which he describes the appropriation of someone’s else’s space through the act of burglary. At this time in Australia and internationally, the appropriation movement in art was in full swing and because of the nature of what I was doing—re-enacting figures from famous European paintings—I was associated with the appropriation movement. I actually felt the idea of the thief was a much more radically critical stance for a woman artist to take because women artists had historically been so marginalised. Their relationship to European masters really needed to challenge that hierarchy. The trickster as a persona allowed me to slip through these gaps in art history and disturb the balance. The trickster character in art was also beautifully described by UK-based art critic Jean Fisher as a way to characterise those artists who use play and irony to disrupt our normal perceptions of the world and its representations. I really related to this proposition.

BD:Your current exhibition Drawn Out 1987/2022 is a combination of photographic and video work. How did this collection of work come to be?

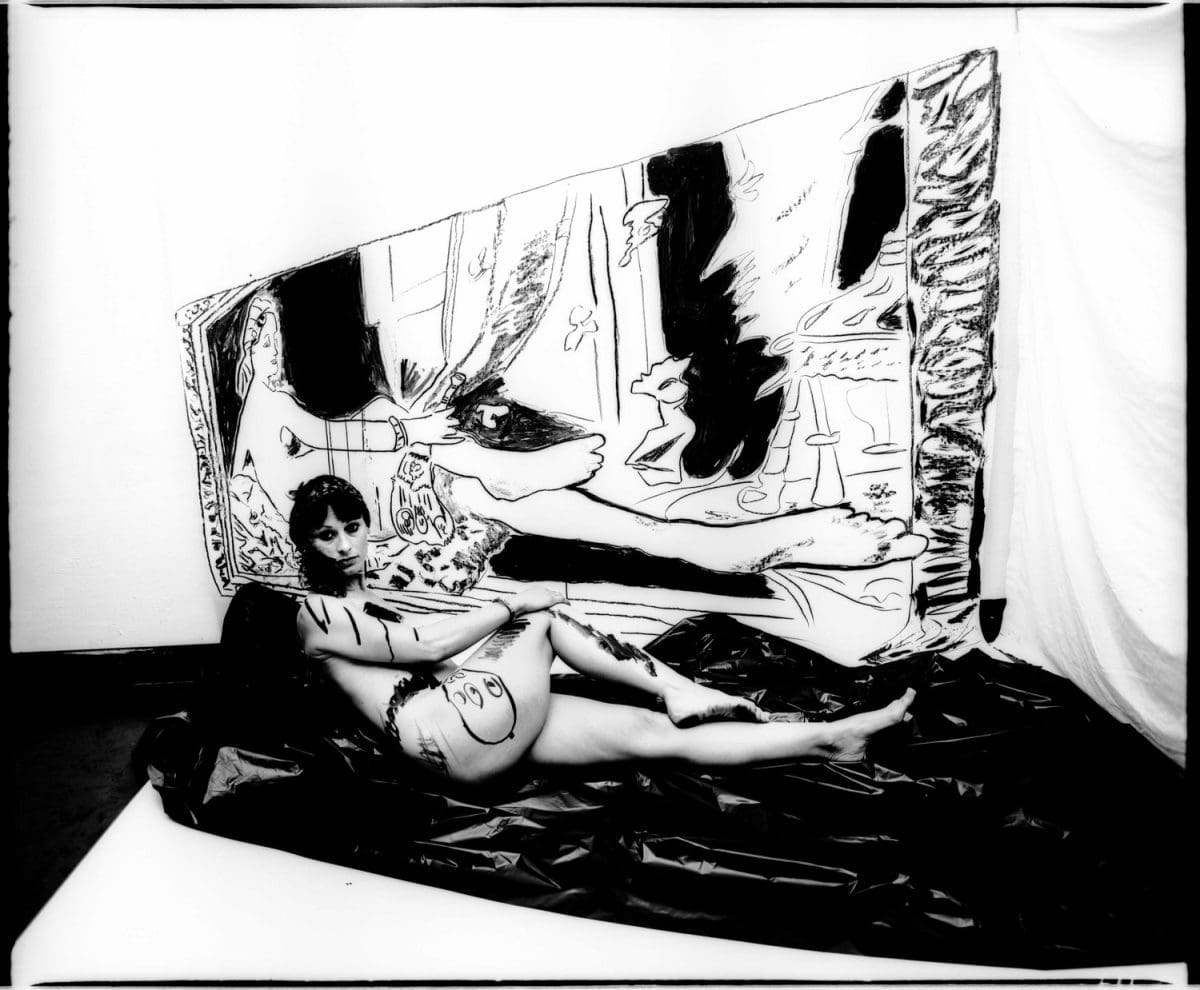

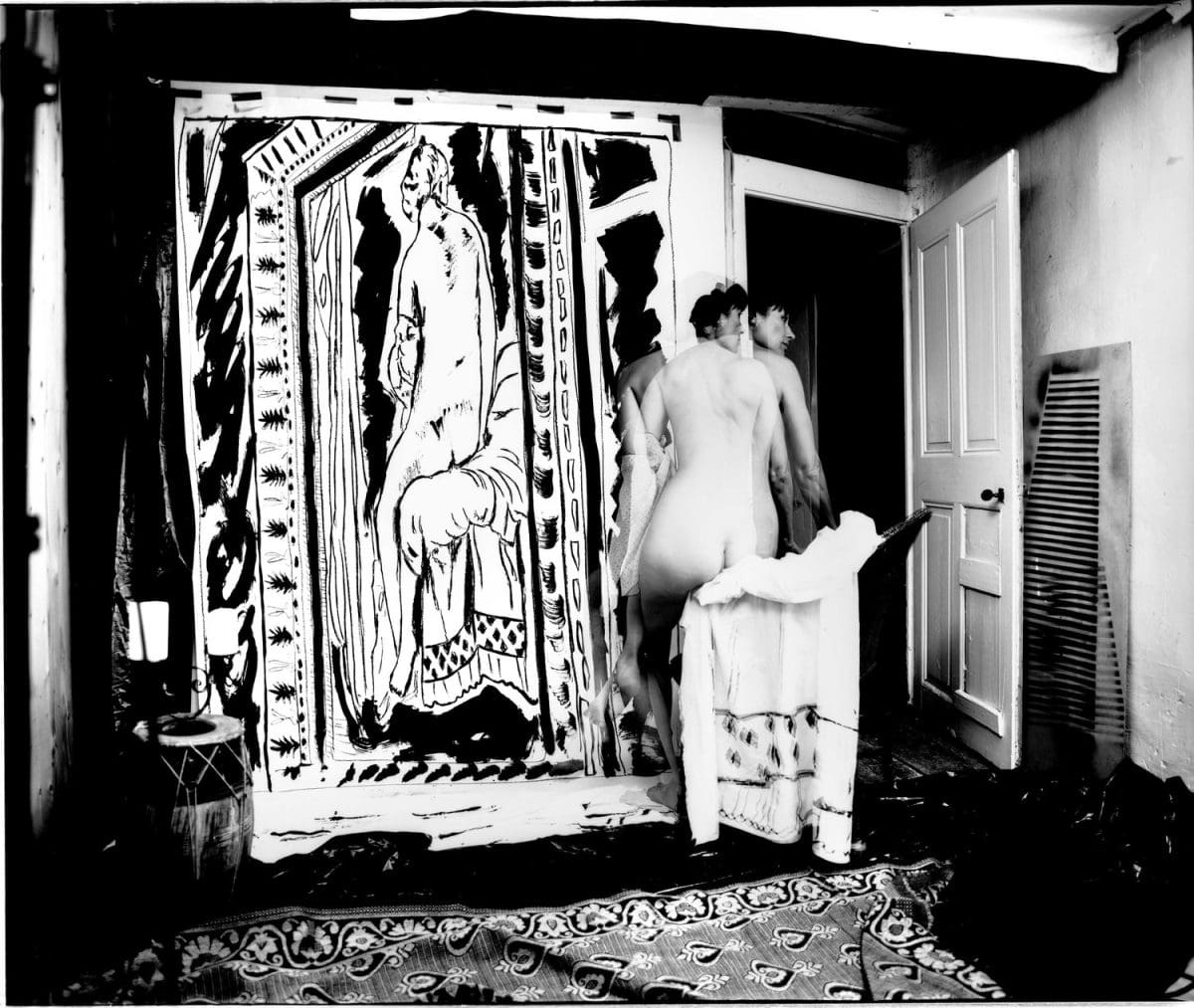

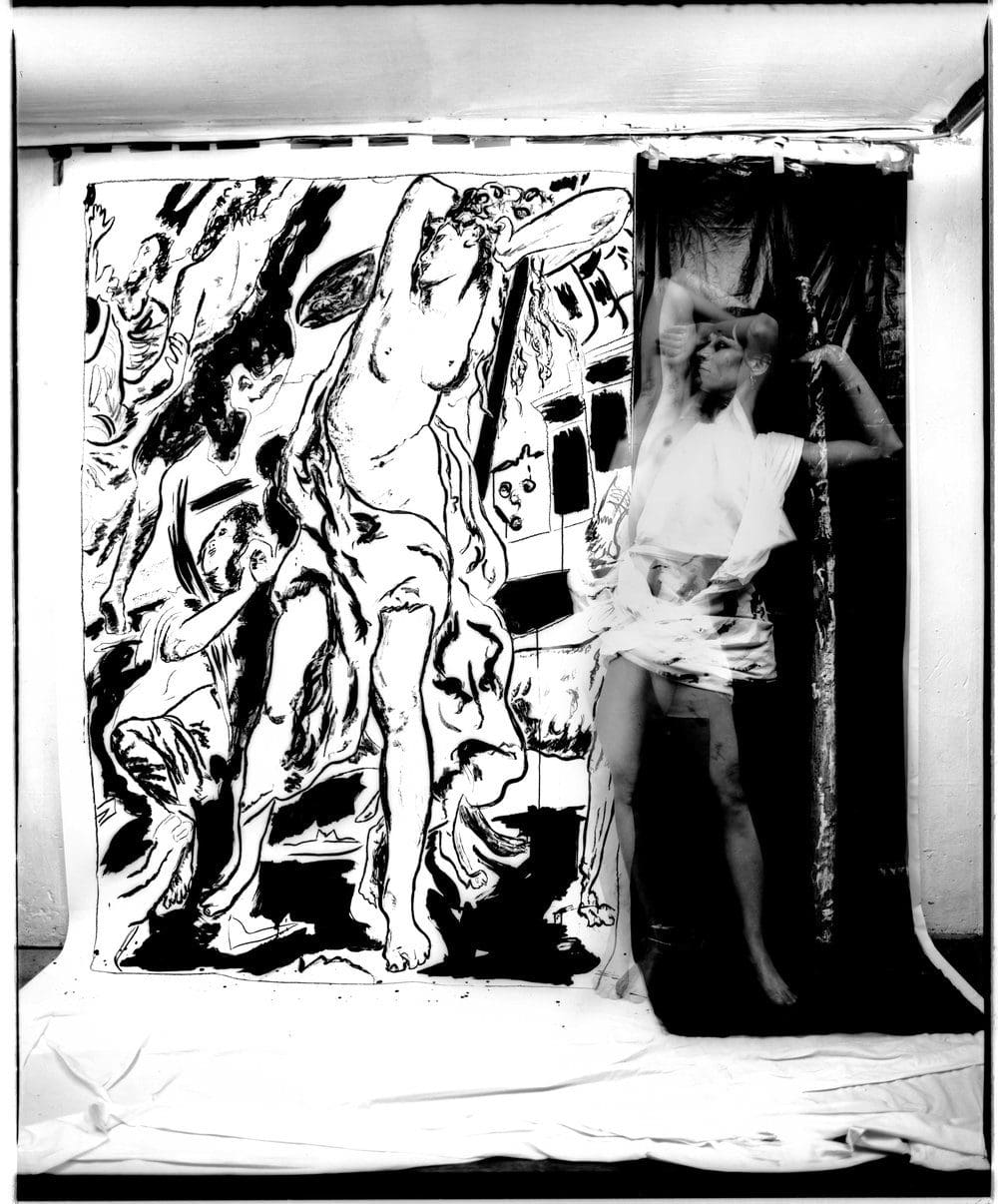

JR: Secret Strategies, Ideal Spaces, 1987 [a collection of images] was initially created while I was living in Paris in one of the Cité des Arts studios. Getting to see all the historical artwork I had previously used in my work but until then had only seen in books, was fascinating. I decided to enter the museums of Paris like a tourist and take quite badly composed pictures and details of these great works, which often contained depictions of women. The slides of these were then projected onto a backdrop so I could make rather crude black and white drawings from them. I performed with these drawings and echoed the poses of the women in the images. The ‘secret strategy’ was the deconstruction of the original works and breaking the ideal space of the museum by infiltrating it with works created by a woman artist. Seems naïve now, but the images carry a sort of innocence in their desire to break down walls and play mischief with history.

BD: What made you decide to create a contemporary response to Secret Strategies, Ideal Spaces?

JR: When Fran Clark, Director of ARC ONE, discussed the possibility of re-printing and re-showing the works from 1987, I felt it was the perfect opportunity to bounce Secret Strategies, Ideal Spaces off an idea I had been thinking about for a while; which was to draw myself in charcoal as a performance work for video. I imagined it as a playful gesture where the traditional nude female life model draws herself. Now, seeing Secret Strategies, Ideal Spaces together with Drawn Out, I think there is a fantastic conversation across time; not only because my body is 35 years older but because it has liberated me from having to perform historical works. Now I am simply drawing for myself. The active quality of the video also animates the stillness of the early photographs.

BD: As a constant observer of society, how would you say images of women have changed (or not changed) over the course of your career?

JR: I think change comes in waves and sometimes those waves overlap. The tide can ebb and flow. If we think of the suffragettes in the early twentieth century and the extreme position they took by marching on the streets and often being brutally treated as a result, contemporary activism like the #MeToo movement doesn’t seem that radical. In my youth, there were the women’s liberation marches and women were publicly dismissed by the focus on their bra burning, or that they wore overalls etc. It was a way to diminish the significance of what women were attempting to expose. All these examples simply demonstrate progress is not necessarily ever fully achieved, or that it can be maintained. All these actions do need to continue and there needs to be continual vigilance by all generations to maintain our freedoms. This is true not only of women’s issues but of democracies generally.

Drawn Out 1987/2022

Julie Rrap

ARC ONE Gallery

15 February—19 March