Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

Trawlwoolway artist Julie Gough spends much time researching her ancestry and the histories of Aboriginal people in Tasmania. Working tirelessly to weave together threads of information found in museums and national archives, Gough seeks to fill in the gaps of documented history by unearthing lost knowledge and encouraging viewers to question the meaning behind historical objects.

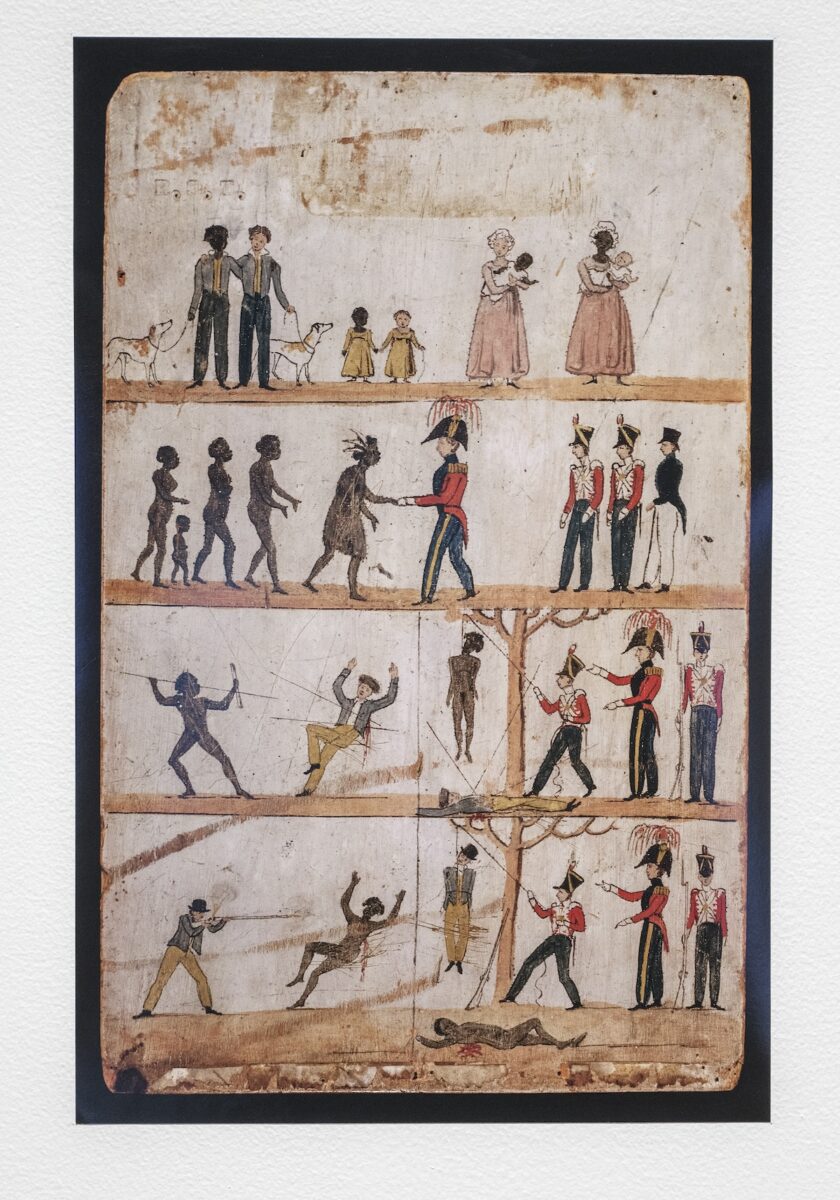

Collected objects are integral to Gough’s work and throughout her career she has utilised items like shoes, cuttlefish bones, soap, shells and tea tree sticks to construct a narrative embracing both her personal history and the colonial history of Tasmania. In GHOSTLAND, Gough returns to a visual reference repeatedly seen in her work—Governor Arthur’s 1828-1830 Proclamation to the Aborigines. Originally printed on board to publicly illustrate how acts of violence would be punished in the same way for Aboriginal people and European settlers, the board used hand-drawn images to present a false declaration of equality.

Together with elements of sound and film, in GHOSTLAND, Gough has reproduced the proclamation board images and brought them into the three-dimensional world. Around the gallery, 31 life size cut-outs of Aboriginal people and British settlers are attached to robot vacuum cleaners, allowing the figures to move around in physical space and cast their shadows on the walls. “The real thing I wanted was mobility of the proclamation panel in order to activate it,” says Gough. “GHOSTLAND is like a Danse Macabre [Dance of Death], the whole feeling of watching the figures move in that jerky way. It does seem a little apocalyptic.”

The culmination of a residency at the Australian National University in Canberra as a 2022 H.C. Coombs Indigenous Creative Arts Fellow, the development process for GHOSTLAND enabled Gough to explore the possibilities of movement. “I’ve never really veered far from wanting to give an audience a way to re-look at something that’s static and reconsider where things might have gone instead of how they went,” she says. “In terms of inhabiting a space and thinking about that, I realised this being a university gallery, I probably had a bit more space for play, possibility and experimentation. And the possibility of more interaction with students and staff than usual.”

In addition to the moving cut-outs, four of Gough’s earlier video works are set up on large screens on the outer walls. “I decided in the end to have the walls encase and stage the figures where they come in and out of the central ground, but they can move behind the panels as well,” Gough explains. Projected within the darkened space is Driving Black Home, 2009, Gough’s first video work focusing on the thousands of land grants given out in Tasmania between 1804 and 1832. To convey how much land was taken by British settlers, Gough filmed all the counties of Tasmania listed in the land grants from a car window, resulting in an almost endless stream of stolen land.

Crime Scene, 2019, is centred around the traumatic experiences of Gough’s ancestor, Dalrymple Briggs, during the time she lived with the Mountgarrett family in the northern Tasmanian town of Latrobe. Elsewhere, The Wait, 2022 is based on archived records documenting the intent of then Director of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Alexander Morton, to exhume the body of a female Aboriginal woman from Latrobe, most likely Briggs. No further correspondence detailing the outcome of this action has been found. And so, Gough waits for history to reveal the truth, knowing it may never come. “I use art to test ideas and look for avenues I know exist but haven’t yet been found, to try to locate more information about what is unfound. When making a work, the worst thing is if you don’t know if something even exists.”

With so much knowledge lost in the decimation of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people combined with the poorly-kept records of the colonial 1800s, a complete picture of the events that transpired during this time seems impossible. The final video work, Invoke | Inverse, 2023, draws upon interactions between the Governor and the remaining people of Oyster Bay and Big River who boarded boats to Wybalenna on Flinders Island under the false pretenses they would eventually be returned to their Country. “That’s kind of the last stand—they waited, made their walk to Hobart and then were exiled to Flinders Island, which they did willingly, very much supporting the notion a treaty was made. It’s just that we haven’t yet found it in written form, which is a haunting problem.”

GHOSTLAND

Julie Gough

ANU School of Art and Design Gallery

25 September—25 October