Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

When Indigenous artists collaborated inland from the New South Wales south coast on making an enormous architectural gunyah (or gunya, meaning house or hut, according to Sydney language linguist Jakelin Troy), their initial wish to fell gum trees to make the installation raised “interesting schisms” and a “cultural tussle” about managing Country, says Wiradyuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones.

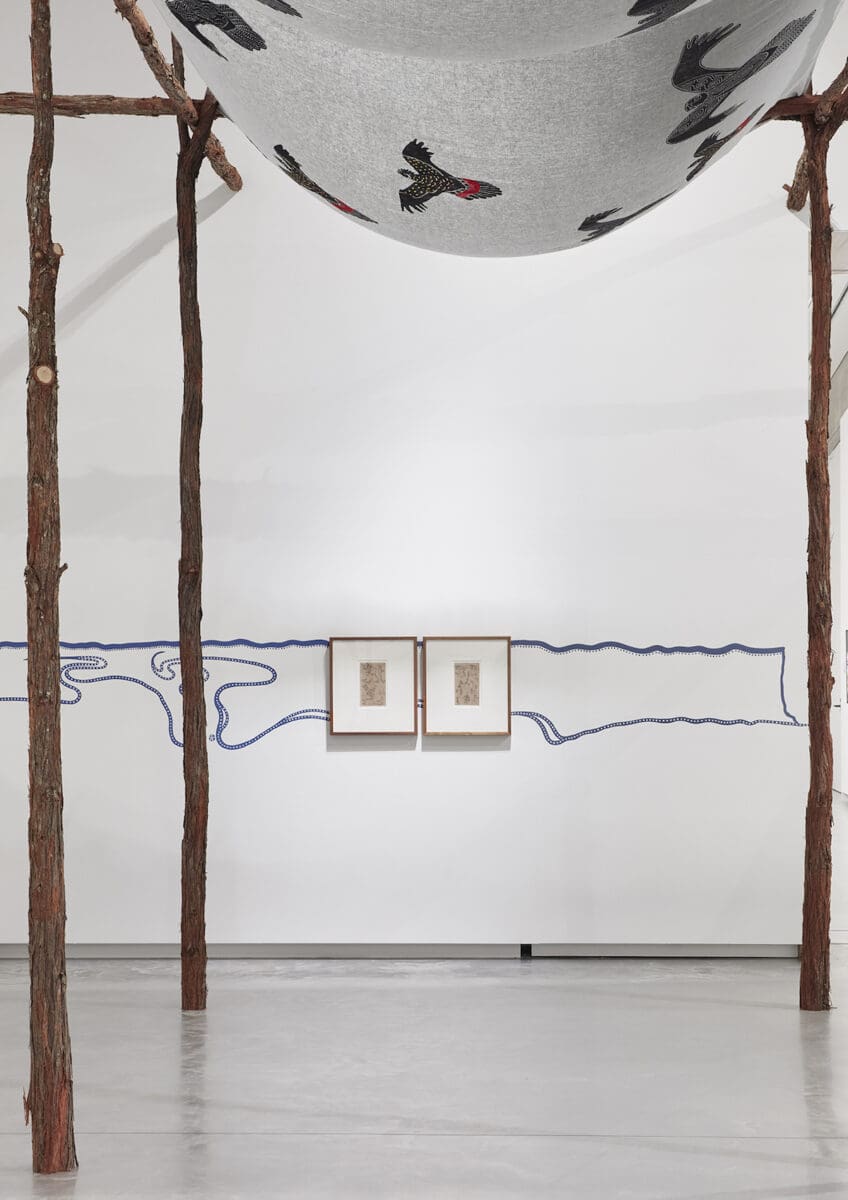

The gunyah was eventually made of 80 turpentine trees, not gums, harvested from around the Bundanon Art Museum site, says Jones, curator of the new exhibition bagan bariwariganyan: echoes of country, who also argues native logging bans are “really strange”. Aboriginal people have been “highly active in managing Country, through burns and making sure eucalyptus forests were kept in check, and we prefer trying to maintain grasslands, so there was a bit of a cultural tussle”, he recalls of the art-making process.

“There was still this clash between Western and Aboriginal science. Working with the local Aboriginal community, fire rangers and Elders, everyone was saying: ‘Yes, just take any of those gum trees, there’s too many’, but of course when you work with the scientists, they were like, ‘No, we’re trying to save those gum trees, they’re very important’. So, we just harvested the turpentine trees from around the buildings, and that was obviously a fire mitigation process, and part of that is managing Country, but [the process] did bring up some interesting schisms in the ways people think.”

Suspended from the gunyah’s tree poles are screen-printed skyscapes by Walbunja/Ngarigo artist Aunty Cheryl Davison, depicting a creation story situated on Cambewarra Mountain. The story goes that the mountain was a burning coal seam, and the curious local white cockatoos came too close, flying through the fire, turning them into glossy black cockatoos (which today are endangered). Aunty Cheryl also presents an installation of new weaving and textile works, building on her research into local Burrawang palm seeds, a traditional food source.

Surrounding the gunyah is a 75-metre mural by Gweagal/Wandiwandian artist Aunty Julie Freeman, illustrating culturally significant bays, beaches, mountains and rivers. Aunty Julie’s first solo exhibition is also part of the season, sharing matrilineal stories of the plants, animals and weather patterns of her Country.

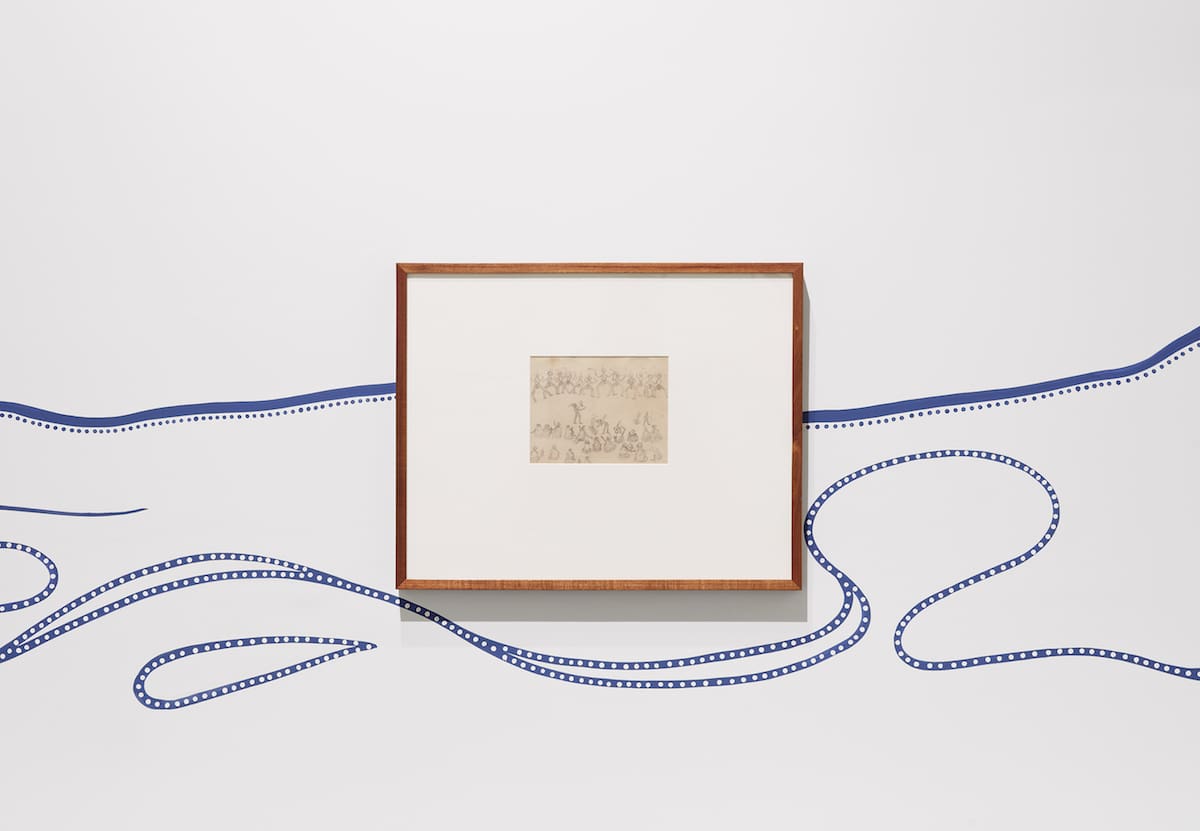

The exhibition also includes fragile 19th century drawings by Yuin artist Mickey of Ulladulla, who was born on the south coast, loaned from the National Library of Australia, the National Gallery of Australia and the State Library of NSW. There are similarities with the contemporary work presented here, particularly the depiction of dancing, ceremonial objects and culturally significant animals.

Mickey’s inclusion is significant in underheralded ways, notes Jones. “To be a contemporary artist in NSW, you’re often labelled as urban,” he says. “Which is strange, because in the southeast we have some of the oldest Aboriginal art movements: for example, the La Perouse Aboriginal art movement.

“Then you go and look at somebody like Mickey of Ulladulla, Tommy McRae, William Barak—men who were painting years before Papunya [in the Northern Territory], years before Albert Namatjira, years before the bark painting movement—but for some reason we’re not seen as authentic, yet we have this extraordinary canon of cultural work happening from this region, which people are just so keen to ignore. “Putting Mickey in there was significant to say that Aunty Julie and Aunty Cheryl are part of a trajectory of extraordinary artists from this region who are building and gathering cultural knowledge and strength through their work.”

There are soundscapes throughout the exhibition, anchoring these visual stories: in the main room, the naming of places and the sounds of cockatoos; in another room, with Aunty Julie’s work, the artist can be heard naming her ancestor women she has painted.

“People have been going to the south coast for generations, having family holidays in summer, thinking about fish and chips and catching waves, which is brilliant,” says Jones. “What we’re hoping is people who come to the show see there’s a lot more to the south coast, this extraordinary cultural narrative sitting underneath the surface there, opening their eyes to what is in their backyard.”

bagan bariwariganyan: echoes of country

Bundanon

Until 9 February 2025