Jennifer Mills is a collector of stories hiding in plain sight. For more than three decades, the Melbourne based artist has quietly explored the everyday, the intimate, and the forgotten. Known for her technical mastery of watercolour, Mills has built a body of work that is as emotionally resonant as it is formally exact. This year, in her first major survey exhibition at Melbourne’s Bunjil Place, Mills’ strange and tender world comes into full view.

Mills’ practice involves falling down a lot of narrative rabbit holes, she explains. “My work has accumulated into this one big, quite autobiographical story—a confluence of memory and experience. It’s like that detective’s wall with the red strings, connecting everything.”

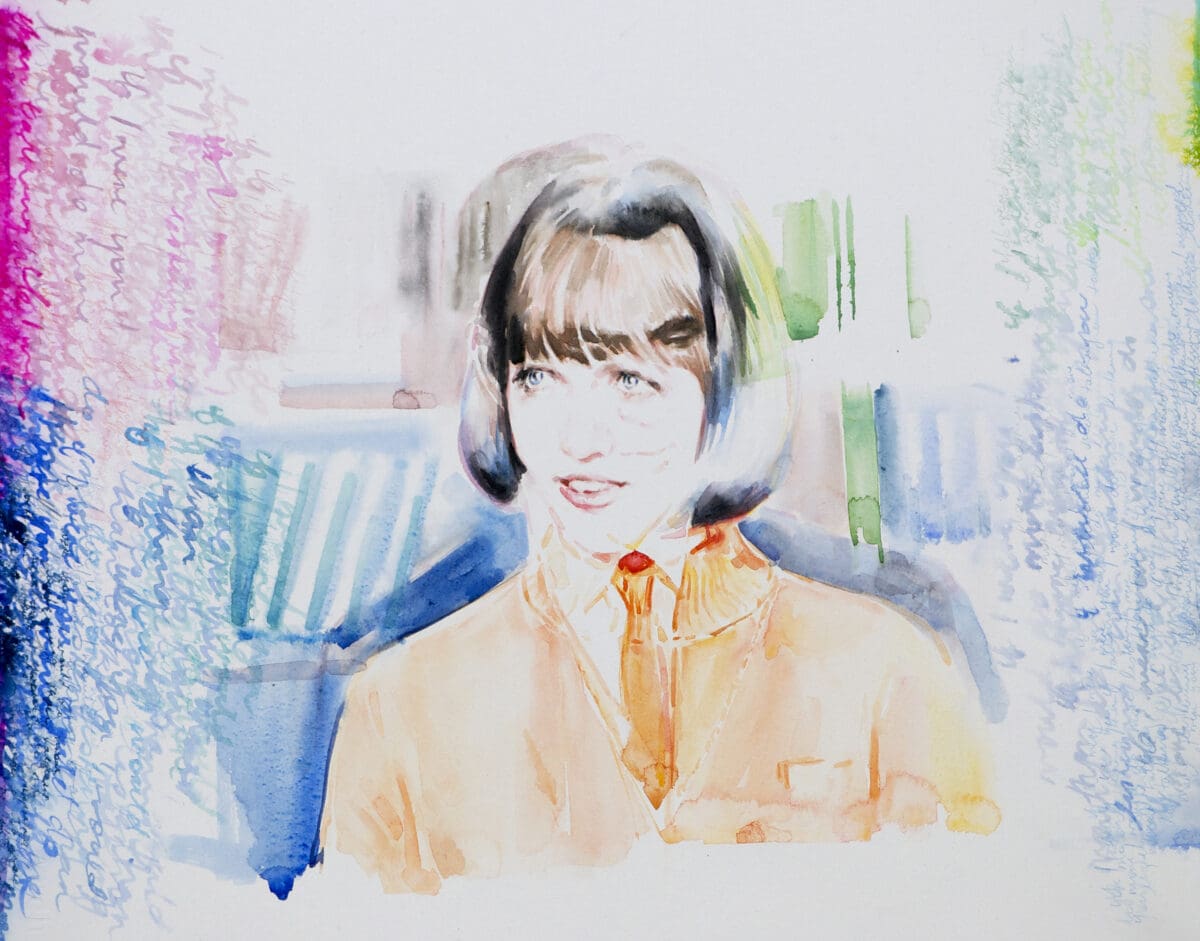

While her subjects vary widely—from birds and houses to internet-found strangers and school photos—her approach is consistently grounded in precision and tenderness. Watercolour, her medium of choice, demands both. “It’s a very light touch. You can’t erase it,” she says. “You have to embrace the mark you’ve made. That was transformative for me. As someone who likes control, watercolour taught me to let go.”

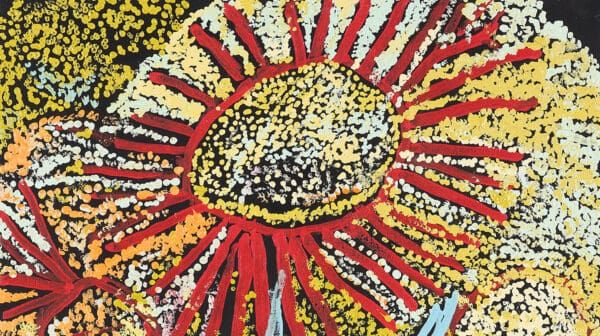

This idea of letting go recurs throughout Mills’ work, perhaps most poignantly in her collaborations with her son, Darcy Luker, who lives with disability. In recent years, Mills has handed her meticulously finished watercolours over to Luker, inviting his spontaneous, unfiltered additions. “He’s deliciously disrespectful,” Mills laughs. “He just sort of bumps me out of the way. But there’s a clarity and confidence in how he sees the world, that I find incredible. Our marks coexist, creating a new energy and a new narrative together.”

This interplay is beautifully explored in Family of Freaks, a series shown at Sydney’s Darren Knight Gallery in May this year. Here, Mills renders Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in classic portrait style, leaving the faces of surrounding family members blank for Darcy to complete. “When I found that photo, I knew I had to work with it,” says Mills. “There was this tension present—a happy family with one member, the black sheep, so often excluded from society but no less wanting or deserving of love. That felt very close to our family experience of living with disability.”

Themes of disruption and reframing ripple through Mills’ work. Her process often involves working from found photographs—everyday images scavenged over decades from op shops, flea markets, and online. In her hands, these small moments become luminous, transformed into watercolours or altered directly with scissors or oil pastel, to subtly rewrite the original narrative. “I’m interested in the micro moments of people’s lives,” she says. “The everyday, the banal, but also the poignancy and relatability in that. Everyone can bring their own stories and meanings to the work.”

The exhibition at Bunjil Place draws together the many threads of Mills’ richly textured practice. “Since opening eight years ago, Bunjil Place Gallery has celebrated contemporary Australian women artists through solo exhibitions and new work commissions,” says gallery curator Penny Teale. “This will be the first exhibition to survey the work of Jennifer Mills and the first solo exhibition of Jennifer’s work in a Victorian public gallery context.”

Curated in close collaboration with the artist, the survey manifests as a constellation of narratives spanning her 30-year practice. Many of the works were initially shown with Darren Knight, who the artist describes as “the true champion of my practice”. The Bunjil Place show includes early watercolour works, selections from the long-running In the Echo Chamber series (2013–present), and recent works co-created with Luker.

“There is a democracy to the subjects and materials that Jennifer works with,” notes Teale. “Her work surrounds narratives that are familiar and personal—family, memory, suburbia, television characters and disability. Working in a domestic scale with materials and processes that are relatable and accessible is also something we know will resonate with our audiences.”

At the survey’s heart is Ron, an ongoing project that began with a bag of discarded family photos bought off eBay. Mills didn’t open the bag for two years. When she finally did, a quiet narrative began to unfold—the life of a boy named Ron, captured in snapshots from the 1950s to the 1970s. As Mills pieced together his story, noting the progression of a physical disability and the compassion and affection that so clearly surrounded him, she was struck by the parallels to her own life. “It’s the story of a regular family, documenting their son’s life with love and care,” Mills says. “I’ve become very personally attached to Ron. And it obviously reflects my relationship to my own child.”

Ron stands as a testament to the resilience of families that often remain invisible in mainstream culture. “Disability is still largely hidden,” Mills notes. “I wanted to bring this story into the light—it’s one we don’t see enough of.”

In this way, Mills’ work acts as both record and reinvention, preserving moments while nudging them lightly toward new interpretations. Her watercolours don’t clamour for attention. Instead, they invite us to pause, consider, and return with a renewed sense of care. Under Mills’ gentle guidance, quiet revelations can speak volumes, if we can just stop a moment to listen.

In the echo chamber

Jennifer Mills

Bunjil Place Gallery

(Melbourne/Naarm VIC)

9 August—16 November

This article was originally published in the July/August 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.