When Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello gathers molten glass from the furnace, she is thinking about Country. Specifically, the exquisite desert plains surrounding Hookeys Waterhole near Oodnadatta in South Australia, where her father was born. “That Country is Stone Country,” she says. “Red and purple and brown pebbles crunch underfoot, the soil is fine and dusty, and the horizons go on forever.”

Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form. Her multidisciplinary career—spanning sculpture, drawing, writing, teaching and cultural advocacy—is rooted in deep cultural knowledge and lived experience. Now based in Kamberri/Canberra, she is widely recognised for her blown glass works that reimagine traditional woven forms like fish traps and dilly bags. These pieces are physically and conceptually layered, drawing from her Arrernte, Chinese, and Anglo-Celtic heritage, and from the stories and places that have shaped her.

As a child, Martiniello visited museums with her dad. These early encounters with the “hideous” museum panoramas that misrepresented Aboriginal cultures as relics of the past left a lasting impact. “My aunties were weavers. It was a living practice,” she recalls. “I knew that. And I wanted to show it.” This sparked a decades-long dialogue between fibre and glass, fragility and strength, past and future. It also instilled a reverence for the economy of design. “Woven objects are such a testament to how sustainably you can live with your environment,” she says. “You make what you need from what the land gives you, and when its life is over, it returns to the land.” Her fascination with glass began through collecting vintage objects and enamelling her own designs, eventually leading her to hands-on training at the Canberra Glassworks. “Glasswork is rigorous and exacting,” she says. “But it’s also addictive. Glass reflects light just as crystal refracts it. It’s a fascinating and extraordinary medium.”

This year, Martiniello has been named a finalist in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAAs), Australia’s most prestigious and longest-running First Nations art prize. Now in its 42nd year, the NATSIAAs celebrate cultural continuity and an unbroken connection to Country. For Martiniello, who won the prize in 2013, the recognition remains meaningful. “It’s amazing to be honoured by these awards again,” she says. “They’ve changed the careers of so many artists. I want to acknowledge the awards, Telstra and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory for providing this platform.”

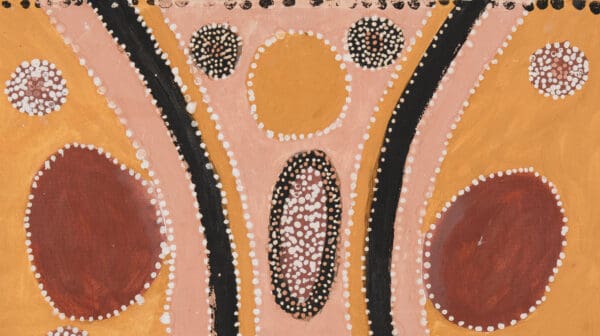

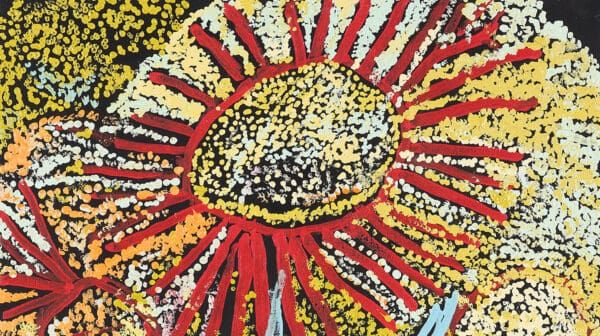

Her finalist work, Painted Desert Continuous Creation Story (2024), marks a departure from her better-known woven forms. The series of six luminous glass ovoids—what she terms “Rainbow Serpent Eggs”—draws inspiration from the Painted Desert, an ancient inland seabed whose songlines pass through her grandmother’s Lower Southern Arrernte Country.

“That landscape is fragile, always changing,” she says. “The colours—white, yellow, orange, red, purple, brown, black—shift constantly. The transitions of colour, the forms, and what I call the paleo scars (or the thaw marks) from the last ice age—they’re all part of the story.”

Through repeated sequences of melting, layering, marvering and heating, Martiniello replicates the land’s markings and colours in thick, translucent glass. Each egg is roughly hand-sized—ranging from 16 to 22 centimetres—but carries a remarkable visual (and physical) weight. “They’re very heavy, because glass is heavy,” she says with a laugh. “But they’re also full of promise. The Rainbow Serpent moved through the land, shaping it, creating sacred places, and left its eggs as a promise of continuing creation.”

Alongside her artmaking, Martiniello is a teacher, writer and community leader who has long championed urban First Nations artists. She has helped establish residencies, mentorships and collaborations that connect independent First Nations artists with mainstream institutions. “A lot of urban-based First Nations artists are out there doing things in isolation,” she says. “They don’t have the networks and support that Art Centres in remote communities offer. So, we’ve worked to create that—starting with a seed, nurturing it, and letting it grow.”

Martiniello sees her art practice as operating on two levels. “I want people to understand that this work can’t exist without the tens of thousands of years of living practice behind it,” she says. “I hope it fosters a deeper understanding of First Nations people, our cultural knowledge and our ways of living sustainably with the environment.” At the same time, she wants viewers to appreciate her pieces as rigorous, materially complex objects of contemporary art. “There are two aesthetics going on,” she says. “There’s First Nations culture, and there’s the language of studio glass. Hopefully, they’re working together.”

Across many years of making, Martiniello has used the delicate strength of glass to hold stories of Country, culture and connection. In glass, as in Country, creation is always ongoing—layer upon layer, catching the light.

2025 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

(Darwin/Larrakia Country NT)

Until 26 January 2026

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.