Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Black, white and red dominate the art of Jenna Lee, an artist who is a Gulumerridjin (Larrakia), Wardaman and Karrajarri Saltwater woman with mixed Japanese, Chinese, Filipino and Anglo-Australian ancestry. Lee’s work explores these overlapping identities, while also interrogating museum and historical archives, alongside deconstructing colonial objects—most pertinently settler-colonial texts.

Working across multiple mediums including sculpture, installation, photography and body adornment, Lee was the 2019 winner of the Wandjuk Marika 3D Memorial Award at the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award (NATSIAA), and has been a finalist in numerous prizes, exhibiting widely. And while her work explores difficult, sometimes violent, colonial histories, Lee is also concerned with creating art of beauty, too.

Here, the artist reflects on five of her recent works.

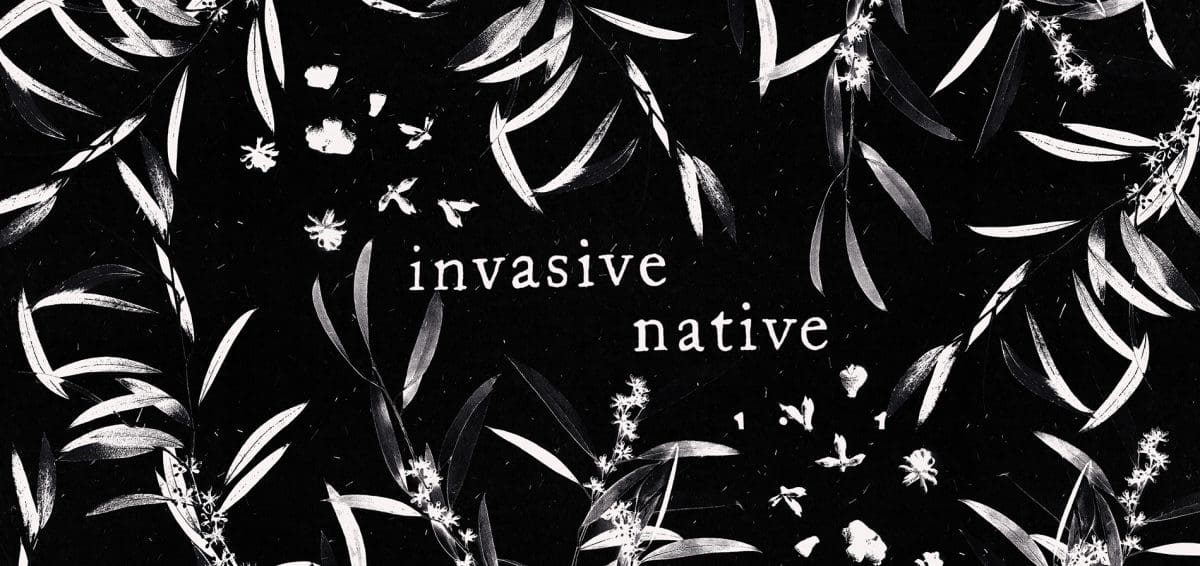

Jenna Lee: This digital print is the last iteration of a series that has evolved over years. The first time it was shown was for a public art exhibition in Brisbane, when I was living in London. I was homesick and I went to Kew Gardens and I was walking around on my own—and then I found four gumtrees. And I thought, “They can’t be Australian gumtrees.” But they were, and they were flowering, even though they’re invasive. I thought, “If those trees can do it, if they’re not meant to be here, then I can be here too. I can do it.”

The gum leaves in the images are collected fallen leaves and branches from Kew Gardens, and I took them—kind of smuggled them—back to the studio in London and photographed them. And this [above] iteration is black and white, because I was thinking about light and dark in museum collections and how through access, we can bring light to these often dark spaces. But also, plants need to survive: this series has always been about homesickness and about surviving in unfamiliar spaces, whether that’s in London, or also surviving in the museum archive.

Jenna Lee: These are experiments with body adornment as an extension of a series I did while living in London and working with ancestral objects. I was in London for research, and I became interested in language and labelling, especially for people who have shifting and overlapping identities. I’m Queer and Aboriginal and Asian, but when I was younger, I felt like I wasn’t enough of any of them to be part of a group. So that’s where the blank label comes in: to talk about self-identifying.

The book I used to weave was an Australian Aboriginal word dictionary. I dissected the book quickly by cutting all the pages away from the spine, and what I really like about that process is that they [the dissected pages and strips] resemble the traditional grasses that my ancestors worked with. And the red Chinese string—the colour red has a lot of significance for my Chinese, Japanese and Aboriginal ancestry, and looking at the red as resembling blood ties—is something that I use a lot in my work. The adornments are also pinned in entomology display boxes, and I got all the materials from an entomology supplies specialist, as I was wanting to interrogate the ways in which we label by also looking at museum collections. I used to work at a museum and the labelling on objects can be open to interpretation: the way objects are categorised can be up to the bias of the labeller. And then there’s an idea of adornment as being how we present ourselves to others, and the way we self-exhibit.

Jenna Lee: I’m interested in the act of deconstructing and reconstructing. It’s a transformative process, and I see books as being constructions of paper, ink and glue and colour. It’s quite elemental. I should say I’m a book designer—I love books and have a good understanding of book anatomy. But I got really interested in thinking about how nature does this transformation best: it’s the ultimate recycler. Fire will happen, and that will create nourishment for the ground to regrow, and grass trees need this act of deconstruction to regenerate. Grass trees grow on my country around Darwin, and I was thinking about the structure of grass trees. I’ve done five in total, and people seem to think they’re very special.

These books in particular [used to create the grass tress] are Aboriginal language dictionaries—but there’s no such thing as ‘Aboriginal language’. There are hundreds of languages. The dictionary just presents words, with no reference to where they came from. It was specifically published by collating compendiums from the 1920s, 30s and 40s, with the purpose to give [non-Indigenous] people pleasant sounding Aboriginal words to name children, houses and boats. And yet the first things that were taken from us was our language, children, land and water. And the reason our words were so widely written down was because [white Australians] were trying to eradicate us. They thought we were going extinct. The deeper you get into it, the darker it gets. But the purpose of my work is to take those horrible things and cast them as something beautiful.

Jenna Lee: This is a collaborative work with my sibling Mackenzie. I took the photos and Mackenzie wrote poems about them. It was made for the Hyphenated Biennial, and this work was for the digital launch during lockdown. I’m not a photographer, but I’m interested in object memory, and objects that have a history. These objects [in this series] relate to the pearl diving industry in the late 1800s in Broome and Northern Australia, where a shell was discovered as containing the largest mother of pearl species in the world.

At this time mother of pearl was the strongest material for buttons. This was before plastic was invented—then the industry collapsed because we have plastic buttons now. So the English button industry was why the pearling industry happened, which is why my Asian ancestry, both Chinese and Japanese, came to Australia.

This photo series is me documenting the objects that inspired the work I present [in the physical Biennial], based on red silk thread, buttons and mother of pearl shells. I wanted the photographs to be very simple. They’re just on black velvet. It’s a luxurious presentation of something precious, but they’re just common objects.

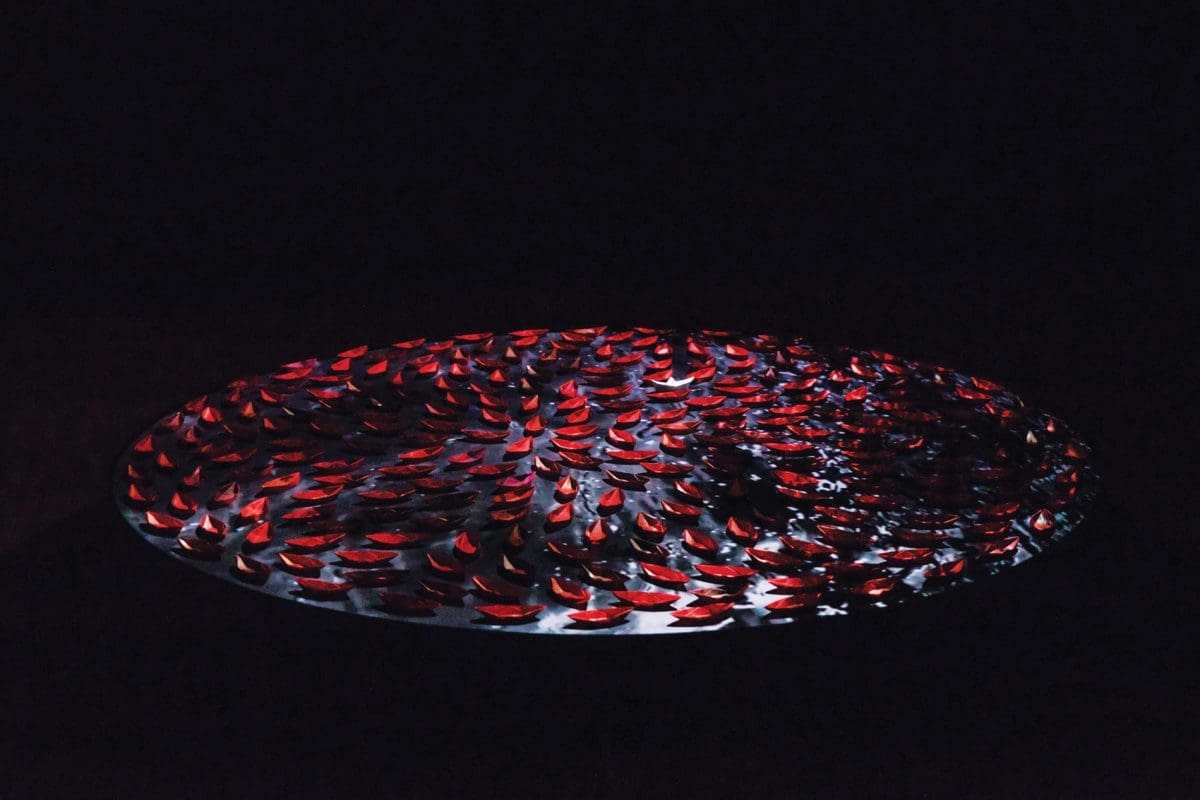

Jenna Lee: I am re-showing this work for Melbourne Art Fair, which I made for the QUT Art Museum show Rite of Passage. It was talking to the 2020 anniversary of Captain Cook’s first arrival. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve ever made, and a huge part of the work is the projection—it’s in a darkened room, and it looks like the boats are moving. It’s 251 paper boats made from The Voyages of Captain Cook, which is a historical book. I was interested in how Australia has this history of boats visiting it: like the Dutch of course, but also trading vessels right through Indonesia and China, all before Cook arrived. I was like, “Why this boat? Why Cook’s boat?” And obviously I know it’s because it started what is now Australia.

Australia has this identity where we think of Cook as being an Australian icon. He wasn’t. He never thought of himself as Australian, and didn’t even really like Australia. So, I wanted to have 250 red paper boats that are in a canoe fold; they’ve got no sail. They’re to talk about all the other boats, canoes, vessels and trading ships that we’ve had as a part of Australia’s history. And there’s this one boat, which is a classic boat fold, and it’s white. It’s there to question why this boat, and to have conversations around Australia’s identity and what we choose to be proud of.

Melbourne Art Fair

MARS Gallery

17 February—20 February

identity, adornment, transformation

Pride Gallery — Victorian Pride Centre

Until late January 2022

Hyphenated Biennial

Various venues in Melbourne’s West

26 November 2021—9 April

Blak Jewellery – Finding Past Linking Present

Koorie Heritage Trust

4 September 2021—27 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.