Blak Design Matters, an exhibition at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne’s Federation Square, will showcase the eclectic and often uncategorisable nature of Indigenous Australian design. Across a range of disciplines, the survey proves that blak design is a living tradition, merging technical innovation and 21st-century technology with historical themes and traditional narratives. Blak Design Matters has been curated by Jefa Greenaway, a Wailwan and Kamilaroi man, who told Barnaby Smith about the mission of the exhibition and how it came to be.

Barnaby Smith: Can you describe exactly what blak design is, as defined by what you selected for this exhibition?

Jefa Greenaway: Blak Design Matters is a snapshot in time of a range of different Indigenous design practitioners, from a range of disciplines, and their work. We’re talking things like architecture, interiors, furniture, fabrics, jewellery and landscapes, essentially to showcase the richness of Indigenous design thinking and to demonstrate that Indigenous people are engaged with a diverse range of professions and areas of cultural expression.

Design disciplines within the built environment have seldom been captured as key areas in which Indigenous people are involved.

Indigenous people are now active participants in shaping the places and spaces we work and live in, the seats we sit on, the clothes we wear, the brands we see and so on.

BS: I understand that the exhibition is the largest the Koorie Heritage Trust has yet hosted. Is that right, and how has it been working with the centre’s space?

JG: Yes it is one of the largest, and we’re looking at 16-18 design practitioners to be showcased. We’re taking over what had been two gallery spaces and combining them into one big open area, based on a purpose-built exhibition design to suit the space. There is also the prospect of it being a national touring exhibition, as it is collapsible and transportable.

What we’re endeavouring to do with the exhibition design is understand the importance of connection with country.

The exhibition design, by Sibling Architecture and myself, is inspired by place and the understanding that we are on Kulin Nation land, and at the same time by the fact that Indigenous country is diverse, and that Indigenous culture isn’t monolithic or homogenous.

BS: The exhibition is intended to challenge the preconceptions about Aboriginal design. For you, what are some of those preconceptions?

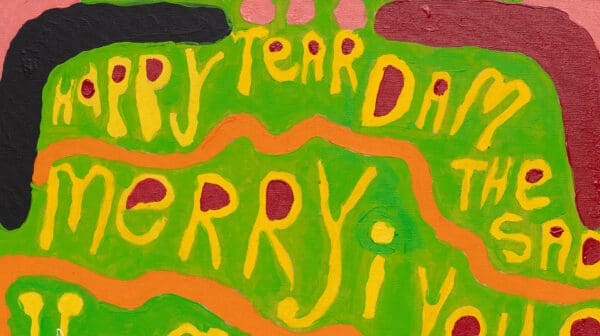

JG: There seems to be a stereotype that Indigenous cultural expression is dot paintings and that that is the only legitimate or authentic form of Indigenous design. The exhibition seeks to explore how there is such a range of design expression, and also that understanding your country is really important because that is often the design inspiration. You’re going to interface with Indigenous people from many different localities, and that will start to break down some of the clichés and stereotypes.

What you will see is also unashamedly contemporary.

People often think that Indigenous culture is somehow fixed in time, but you don’t exist on this vast continent for 67,000 years without the ability to adapt and evolve. Indigenous culture is a lived culture, and that’s something we wanted to clearly express.

BS: Can you tell the story of how you came to curate the exhibition?

JG: It startedwith a public conversation at the National Gallery of Victoria as part of Melbourne Design Week about 18 months ago. It was about unpacking what blak design is, if it matters, and how Indigenous voices are starting to shape our places. The moniker Blak Design Matters is about reclaiming language and acknowledging that Indigenous voices are key contributors to creative endeavours.

BS: An impossible question, I know, but can you identify any work or artist you are particularly excited about in the exhibition?

JG: Well, I have to say all of them, but there are a number of pieces I particularly enjoy seeing and a number of designers who probably fly under the radar. The jewellery design is a real highlight, in particular the work of Maree Clarke which is a really nice fusion between the contemporary technology of 3-D printing and a strong cultural sensitivity that draws on history.

I also particularly enjoy the multi-discipline work of Grace Lillian Lee – so colourful, vibrant, edgy, contemporary and playful. I also love the work of Paul Herzich, a landscape architect whose work is evolving into public art and communication design.

Then we’ve got the work of Dillon Kombumerri, one of the pioneers of Aboriginal architecture, and great work in interior design and furniture design by Nicole Monks and Francoise Lane.

BS: For the uninitiated, can you identify some of the most influential figures in Indigenous design over the last 100 years or so?

JG: One figure I think many people aren’t necessarily familiar with, but who is on our currency, is the Ngarrindjeri man David Unaipon, an industrial designer. He was born in the early 1870s and died in the late 1960s, and designed things like rotors and sheers. I would also name Balarinji as a key design firm, founded by Ros and John Moriarty. They started back in the early 1980s and are very significant designers in communication design and branding – you will have seen their work on the side of Qantas planes.

But we need to acknowledge that Indigenous designers have always existed.

For example, going back in time 7,000 years to before when the pyramids were built, the Gunditjmara people of southwest Victoria created a sophisticated agriculture system that harvested lava stone and used it to channel eels and fish and to create settlements. This debunks the myth that Indigenous people were always nomadic and demonstrates that there were sophisticated settlements and stone houses.

BS: In your opinion, how well do existing education institutions serve upcoming Indigenous architects?

JG: It’s a challenge. Probably fewer than 20 Indigenous people have ever graduated from national schools of architecture. There are fewer than five registered architects in private practice nationally. So the numbers are still fledgling, but what we are seeing now is an emerging number of students coming through universities – about 50 across Australia – studying different design disciplines. We’re well placed to actively become contributors in the design of key places and spaces, as there are a large number of infrastructure and cultural projects along the eastern seaboard of Australia.

BS: You have previously spoken about blak design in terms of “a tangible expression of identity in the built environment.” Can you expand on this by citing some particular examples of expression of Indigenous identity in architecture in Australia?

JG: One good example that I am intimately familiar with is the Koorie Heritage Trust itself. I was involved with its design and its move from the literal and figurative fringes of the city into the beating heart of the city at Federation Square, the cultural hub of Melbourne. The move was a key moment in that Indigenous culture was seen as being of equal value to the other cultural anchors in Melbourne.

With this particular project, we embedded a narrative that connected to country. It was a river narrative, a water story, infusing the architecture and design of the centre because it overlooks Birrarung Marr, or the Yarra River as its better known.

BS: Is it correct that you were the first Indigenous architect to be registered in Victoria? If so, how did that change your life and career?

JG: These things are always difficult to validate, but quite possibly. And with that comes responsibility – I have an acute sense that I need to give back. I spent a decade in tertiary education and I feel compelled to pass on knowledge and use the platform I’ve been uniquely given to demonstrate that this domain is important.

It’s critical to empower others and find means to allow more to contribute to this space.

BS: Can you distil what blak design means to you and summarise why it is such an inspiration in your professional and creative life?

JG: I think many people’s reference to Indigenous culture comes from a deficient discourse. Blak design to me is aspirational, something that raises it to a level that talks to success and opportunity, and is very positive. It allows us to draw on where we are, rather than applying a lens from somewhere else – the internationalisation of cultural expression. Drawing on connection to country is the starting point.

Blak Design Matters

Koorie Heritage Trust

21 July – 30 September