The 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art teamed Sydney-born artist Jason Phu with Hong Kong-born artist John Young Zerunge to take a fresh look at the 19th century riots on Australia’s goldfields, where resentment at Chinese miners boiled over.

Their show, titled The Burrangong Affray, makes connections with the racism that informed official immigration policy in Australia, but as Steve Dow discovered when he interviewed Jason Phu, these horrific historical events still resonate today.

Steve Dow: Lambing Flat, near Burrangong, was an earlier name for the NSW township of Young. What led to the infamous riots there in 1860 and 1861?

Jason Phu: A lot of people had been moving around and not finding gold. The mining was alluvial, and the European miners often worked alone, but the Chinese, because they were used to working communally as farmers and for long hours, they mined in these big teams, often under contract, sending money home.

There was a lot of resentment towards the Chinese, even though the Chinese were finding their gold through hard work.

The Chinese spoke differently, they looked and dressed differently. They had these pigtails. There were these ‘roll ups,’ involving marching bands to call European miners up to evict the Chinese.

European miners torched the Chinese miners’ tents, and kicked and beat them and ripped their pigtails off at the skin.

SD: The Burrangong Affray is an odd term for a show about violence against Chinese gold miners. Did white Australians use affray as a euphemism?

JP: The 4A curatorial team came up with the title for the show, and when I first saw the word I thought, “Oh, ye olde English.” Back then, the police would have used it.

In these no-holds-barred times when such strong words are being used all over social media and between our politicians, it’s the most appropriate way to approach a subject that’s delicate and still has repercussions. It eases the viewer into the history.

SD: I understand this violence against the Chinese, which had already occurred in the Victorian goldfields, led to crackdowns by the states on Chinese immigration. So the violence was then a precursor to the federal Immigration Restriction Act of 1901?

JP: The historian Karen Schamberger, who was on board for the whole project, told me that two of the European riot leaders ended up going into government, so they would have influenced things. So those acts came about, and became the White Australia Policy.

SD: You and fellow artist John Young Zerunge were brought together by the curators and undertook residencies in and around Young, NSW. What made you want to respond to this particular historical moment?

JP: It’s a lot of things. It’s me looking how I look as a Chinese Australian, and how people choose to react in a derogatory way. That’s happened since I was a child.

So there was that underlying feeling, but that’s quite a raw, angry, direct emotion, and I wanted the project to be viewed truthfully, to approach it with some distance.

I’m not from the same area as those Chinese miners, and that culture is quite different. They were mostly from Guangdong, which was Canton, the southern regions of China. My mum comes from Beijing and my dad is from Vietnam, although his family are originally from the most southern islands of China. I was born in Sydney.

A lot of these people who came to Australia weren’t just gold miners. There were market gardeners, furniture makers, everything. They were an integral part of the community.

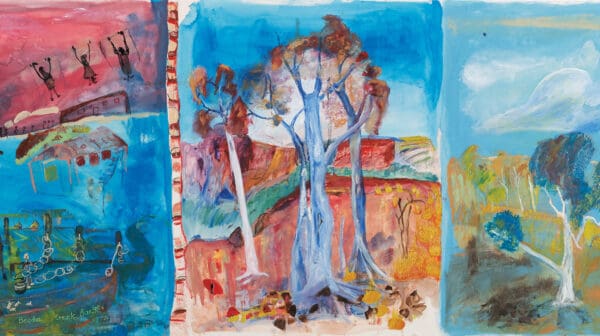

SD: Tell us about your works that will be going on display at 4A.

JP: I did a series of performances in Young that were filmed. For me it was about the journey of the Chinese. I’ve also done some paintings. John is exhibiting a video, photographs and some drawn works.

At Blackguard Gully, where a riot happened, I did an interpretive Chinese dance, which was filmed. I created my own lion costume, out of a tent. I liked the duality of the idea that during the riot there would have been this marching band, and noise, and fire that is traditionally supposed to bring in good luck actually brought this horrific incident.

I’m not a Buddhist monk or a shaman or anything, but the dance was intended to cleanse that history.

I did a burning on Currawong farm [where Chinese miners were given shelter] of the word queue. I got a giant rope and wrote the word queue out with it. Queue was a word used to describe the Chinese hairstyle with a pigtail. But to me it was also like the idea of queuing for immigration in Adelaide. A lot of the Chinese landed in Adelaide and walked all the way to the NSW goldfields, without maps or compasses, to try to avoid the restrictive taxes levied on the Chinese there.

SD: What stays with you from your residencies in the area?

JP: The most surprising thing I saw was the flag the European miners used, the infamous banner used during the last riot. It read, “Roll up, roll up, No Chinese”. It looks like the Eureka stockade flag, but it has been shifted a bit, so that it’s an X, rather than a cross.

SD: A bit like taking the Southern Cross constellation and using it as a white nationalistic symbol?

JP: Yeah. If you Google it you will be able to see it. It’s kept in a museum in Young.

I always come back to this idea of how the Lambing Flat riots weren’t even about the Chinese. They were about a bunch of drunken, down-on-their-luck racist arseholes. I feel like the 2005 Cronulla riot was just that same thing. How did that happen?

The Burrangong Affray

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

29 June – 12 August