Life Cycles with Betty Kuntiwa Pumani

The paintings of Betty Kuntiwa Pumani form a part of a larger, living archive on Antaṟa, her mother’s Country. More than maps, they speak to ancestral songlines, place and ceremony.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Ceiling Centre II (Blak), 2020, plaster, oxide, fibreglass and stain. 60 x 440mm dia. Photograph by Jim Cullen.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, From Bones and Bellies II, 2022, pigment print on backlit film, LED lightbox, 110 x 170 x 7.5 cm.

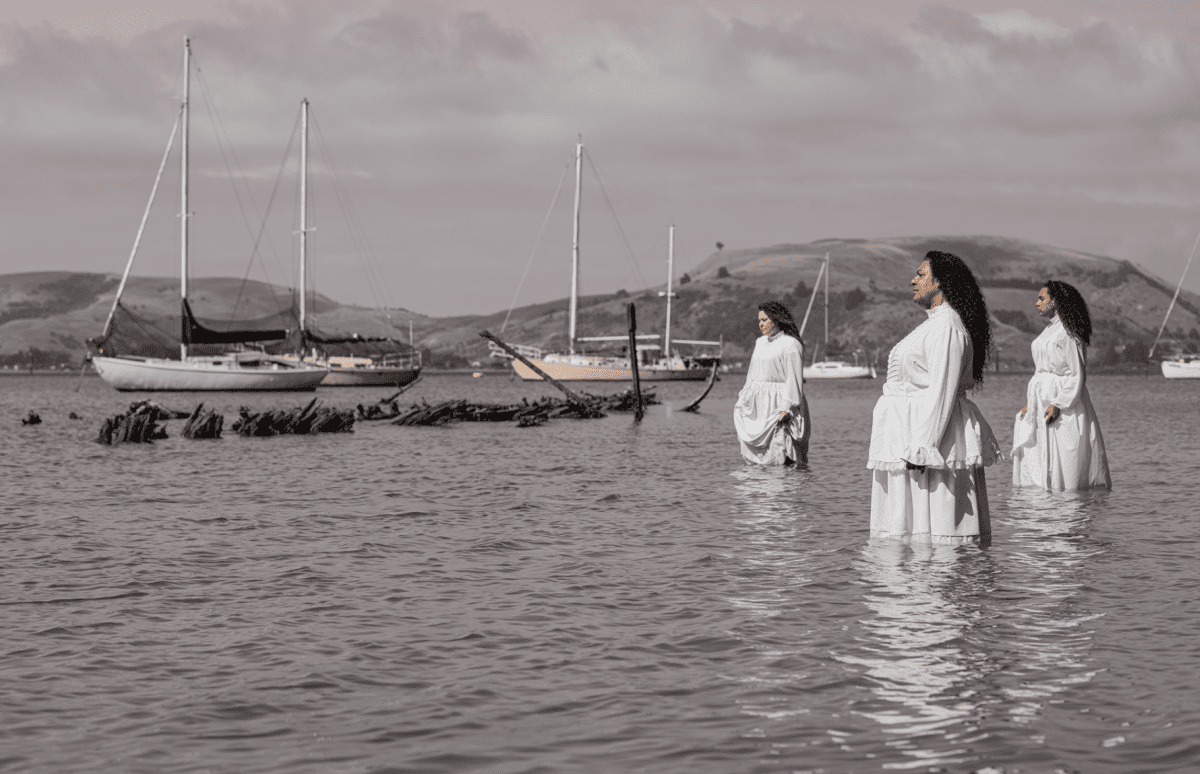

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Open City (In Suspension), 2022, mixed media, 2600 x 9600, in Declaration: A Pacific Feminist Agenda, Auckland Art Gallery Too o Tamaki, 2022. Photograph by Paul Chapman.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Open City (In Suspension), 2022, mixed media, 3600 x 9600mm, in Declaration: A Pacific Feminist Agenda, Auckland Art Gallery Too o Tamaki, 2022. Photograph by Paul Chapman.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Passage, 2022. crow wings, crow feathers, pexiglass, stained wood, mixed media. 1740 x 1020 x 320mm.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby, ‘Centre Flower no. 335’, 2020. Backlit film, aluminium lightbox 1250 x 1250 x 150mm. Photograph by Ryan McCauley.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby is a fourth-generation Australian South Sea Islander artist. Her great-great-grandparents were taken from Vanuatu as children during the Pacific slave trade and made to work in Australia. Togo-Brisby explores this dark history, and its present-day ramifications, through photography, filmmaking and sculpture. Ahead of her inclusion in Other Horizons at Fremantle Arts Centre, we asked Togo-Brisby 20 questions.

Describe your practice in seven words?

Unapologetically Australian South Sea Islander all day.

Your first art love?

Adrian Piper.

Why do you think you were drawn to art making?

I’ve loved creating ever since I can remember. Growing up we didn’t have much, so me and my three big sisters were always using our imaginations to keep ourselves occupied. One of my favourite things as a child was to rearrange the furniture in our house. I was intrigued by the way I could manipulate and transform spaces just by shifting things around. It drove my mother crazy; she’d often come home from work late at night and trip over my new layout in the dark.

That process of playing with space is part of my practice today. So, I think it was my natural ability and passion combined with wanting to say something to the world. It’s said that your first memories of looking at South Sea archives is how your interest in photography began.

What are those first memories?

It probably started earlier than that. My first memories of photography and South Sea archives are my family’s archive. I remember sitting at Nan’s, Auntie’s and Uncle’s houses with old biscuit tins holding our most treasured possessions, all piled on the kitchen table, with photographs handed around. There’s something quite special and almost ritualistic about those moments, learning who we are and where we come from.

The institutional archives provide a different experience: when we are in that space, we are usually researching family history, using photographs and documentation to retrace vital missing links of our ancestors’ stories and their journeys to Australia.

Your research examines ‘blackbirding’, a colloquialism for the Pacific slave trade where between 1847 and 1904 over 62,000 Indigenous peoples across the Pacific were displaced and enslaved on sugar plantations in Queensland. How did this become central to your work?

It’s central to who I am and the reason why I became an artist. Our ancestors were forced to migrate to Australia and their experience is what created our culture as a uniquely Australian Pacific slave diaspora. Our history and contemporary culture is still relatively unknown—I like to look at my practice as away of creating South Sea spaces of belonging. It was after I had my daughter Eden in 2006 that I decided to pursue studies and a career in the arts, attempting to make change the only way I know how. I wanted Eden’s experience as a South Sea Islander to be easier.

Your art not only centres on past injustices of slavery, but also the very real and present-day effects, even as lived by yourself—how did you come to that focus?

It’s all around us, but many people don’t look at the world that way. It’s often not questioned how and why things are valued and preserved, or how wealth is built. It’s always been in my work, but I started to be more overt with this concept when my Auntie gave me a pivotal piece of evidence which links my great-great-grandparents to the family who enslaved them. Due to that family’s wealth and status, I was able to research them, their business and their travels extensively. I spent months online and in research rooms, hoping to find further hints of my own family.

That time spent trawling archives was incredibly emotional and heart breaking for me. It became evident that the treatment of mundane business documents was given more value than our ancestors’ bodies, who were often not recorded or were recorded incorrectly. So, through my work I’m looking at that disparity between preserving the public legacy of slave owners and the invisibility of the Pacific slave trade.

The former prime minster Scott Morrison erroneously, and terribly, declared in 2020 that there had been “no slavery” in Australia. Do remarks like that have ramifications for your art?

Not particularly. I wish I could say I was surprised to hear his comments, but I’ve heard it all before. That type of ignorance just reaffirms why I do this in the first place.

Your works often feature black, white, grey and sepia tones—is there a reason for these colours in particular?

It just happened. Working with materials like sugar, paper sugar bags and ambrotypes solidified that pallet. I don’t force a colour upon a work: during experimentation stages I obviously try different colours, but the materials always resist if it isn’t right.

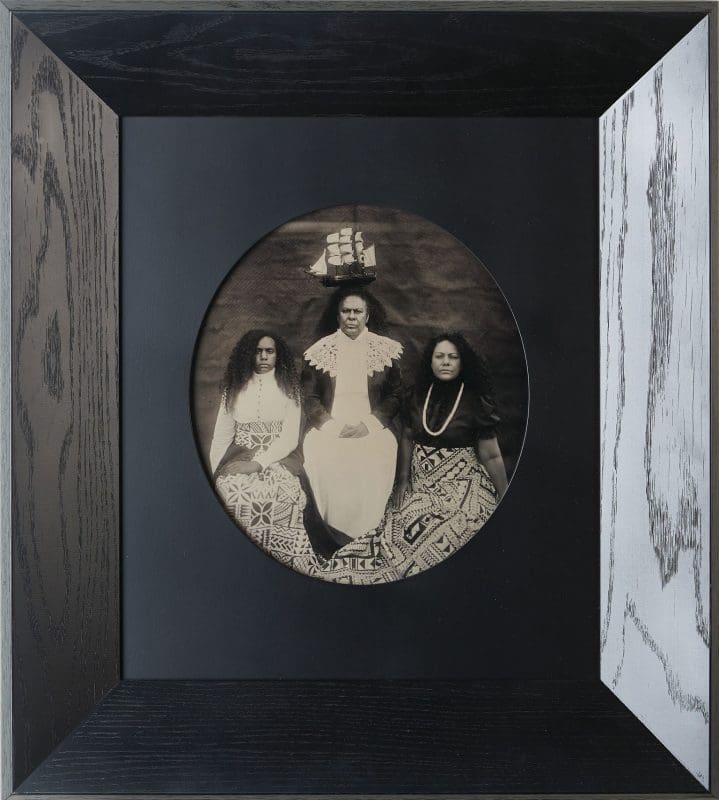

Among painting and sculpture, your practice also involves working with early photographic techniques. What techniques are these, and why have you chosen them?

My research guides my practice. Between 2015 and 2018 I was quite deep into South Sea archival image research. I was spending a lot of time online and also in Queensland State Archives where I could be with our images physically: this made me consider the space in which our ancestors’ images live and how they are available to the public and used by anyone writing on our history. I was thinking of other ways we could be represented and decided to create a counter archive. That’s when I attended workshops to learn how to produce wetplace/ambrotype (collodion process) photographs, a medium which was frequently used by historical photographers capturing South Sea imagery.

What does a normal day look like for you?

It depends what I’m working on. When preparing for photoshoots much time is spent making costumes, test shoots and compositions, as opposed to what I’m working on now which involves full days of mould making and casting. Alongside making, the days have handfuls of emails, calls and meetings, plus tending to our new puppy Peanut and running my daughter Eden around. I try to leave the studio by 6pm, then I usually go back or spend time in the office for a few hours once Eden and Peanut are asleep.

If you could collaborate with any artist, dead or alive, who would it be?

I don’t think I’d be any good at collaborating! I’ve tried in the past but I’m too focused on outcomes. Although it would be cool to hang out with Carrie Mae Weems.

Quick advice for young artists?

Know who you are and what you stand for; always follow your own north star.

Best time of day to create?

First thing in the morning at 5am. Everything is quiet, nobody is calling or emailing, and my brain is fully fuelled. It doesn’t get any better than working in my pyjamas.

Are you a good cook? Any signature dishes?

I’m told that I am: I get asked to make my coconut fried scones and my slow cooked pork.

The most interesting thing someone has said to you about your work?

There’ve been quite a few stories over the years but in the interest of keeping it short: “I can hear them.”

How do you decide what medium to create with for any given work?

While it’s all intertwined, I will usually decide on the medium first, selecting it for conceptual reasons. I’m often thinking of materials that our South Sea community would be able to see themselves within and/or resonate with, at other times I’m speaking directly from my family’s story.

As political as your art is, I also find it very exquisite. Do you find there’s a balance between apolitical work and a beautiful one?

I don’t see my work as very political: it’s more that identifying as South Sea Islander is inherently political. I enjoy the challenge of making beautiful work because this subject matter could quite easily be grotesque. I love that point where beauty meets disturbing, and how it’s jarring for the viewer. I consider my approach as subverting ‘blackbirding’. My ancestors were lured onto ships with trinkets and beautiful things, mirrors shining in their eyes from the ships, for example. I like to think that I use a similar tactic to lure the viewer in. An art experience that’s stuck with you? One is visiting Plantation Voices: Contemporary Conversations with Australian South Sea Islanders at the State Library of Queensland. I was living in Aotearoa, New Zealand, at the time and the day I visited a big group of South Sea Elders walked through the door: they had spent the day travelling to see the show. It was a special moment to be in that space with them, connect through our families, and talk about the archives and art.

Best advice you’ve been given about making art?

The advice that I didn’t take: “Tone it down a little, you’ll scare people off!” This was early in my art journey and it’s great advice because it made me think about who I was and what I was doing—and if I wasn’t going to give it everything then there was no point in making art.

What will you be showing in Other Horizons?

A selection of works created over the last four years, including a suite of ambrotypes from my Adrift, 2018-19, series, a selection of sculptures created from crow wings and crow feathers, some plaster ceiling rosettes, and a moving image work.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby is currently showing at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane.

It Is Not a Place

Jasmine Togo-Brisby

Institute of Modern Art

On now—16 June