Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

While developing Japan Supernatural, Melanie Eastburn, senior curator of Asian Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), did not experience any paranormal phenomena. She has, however, lived in a haunted house. “It was a house where you could always hear someone’s footsteps above you when no one was home,” she recalls. “I could hear light switches going on and off, but no lights came on. Everyone who had ever lived in that house had some experience of this strangeness.”

With a lifelong love of Japanese folklore, Eastburn is not afraid of ghosts and monsters. For Japan Supernatural, she has combined historical and contemporary pieces from the AGNSW vaults with works drawn from international collections to illustrate the prevalence of the supernatural in Japanese art and culture. Part of the Sydney International Art Series, the exhibition contains over 180 items. The works range from tiny netsuke (miniature carvings), delicate Edo period (1603–1868) woodblock prints and manga, to textiles, photography, video and sculpture by contemporary Japanese artists.

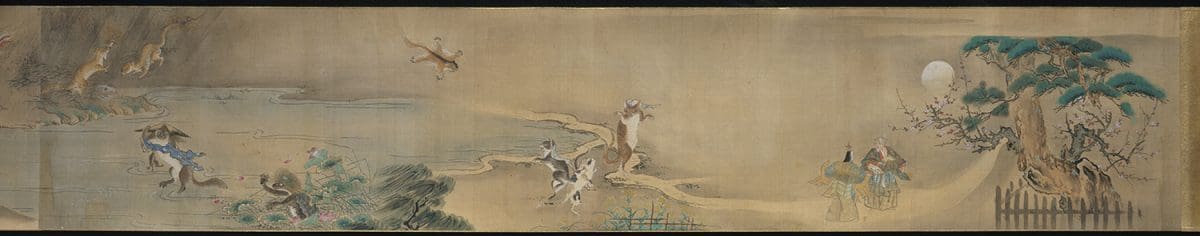

Going deeper into the Japanese spirit world – the miasmic realm of fantasy existing just beyond reality – reveals a similar array of legendary beasts populating the dark recesses of nature and the underworld. In these magical realms humans become shapeshifters with the ability to cross over into the animal world, while creatures like the kitsune (a white female fox) and kappa (a water dwelling humanoid fond of cucumbers) are the protagonists of moral tales – warning of danger, encouraging good behaviour or acting as talismans of protection.

“It’s interesting to me that once you start looking for these beings from the supernatural realm, they turn up everywhere – hiding as tiny objects in the lining of people’s clothing or a ghost painting hanging in someone’s house,” says Eastburn. “The supernatural was so much a part of everyday life.”

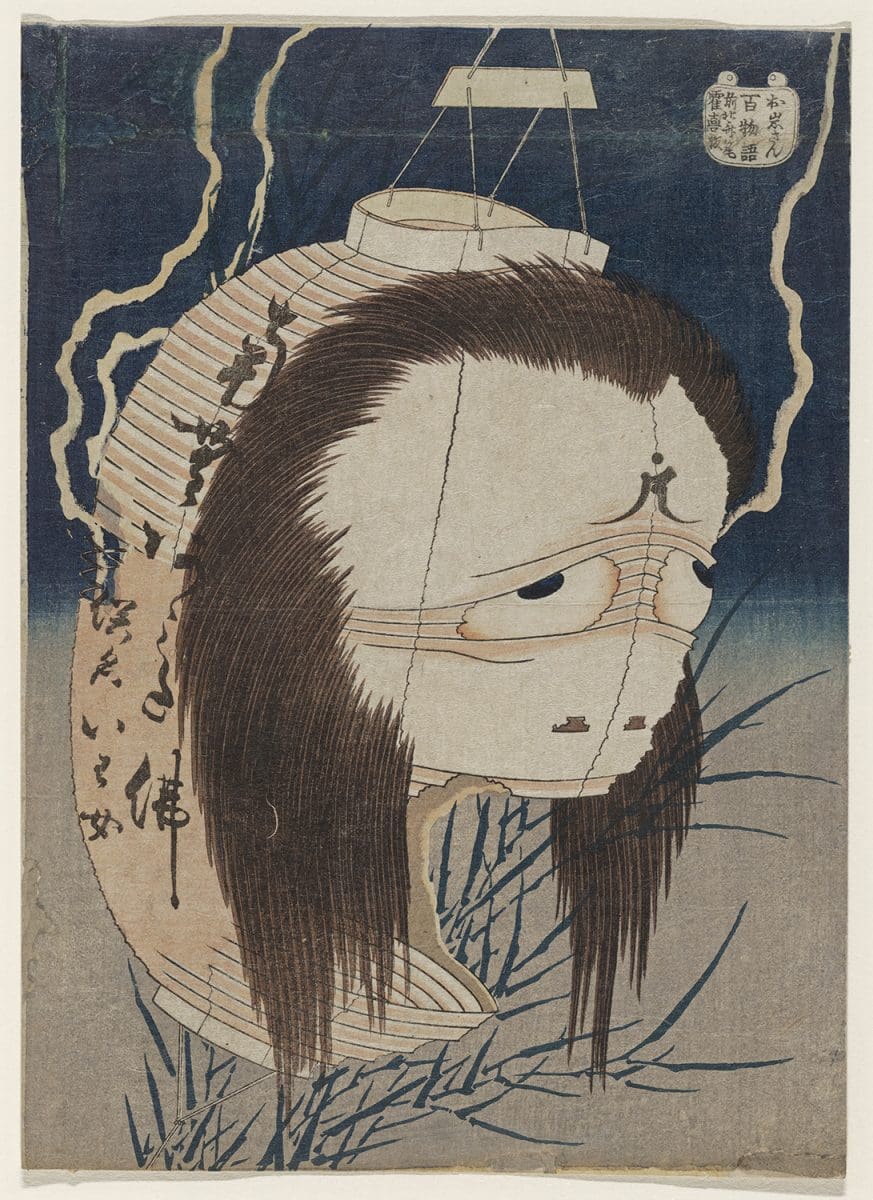

This melding of the supernatural and everyday life became increasingly evident in Japanese culture with the introduction of affordable printing technology in the 17th century. The accessible and easily disseminated ukiyo-e print was a popular form of woodblock printing in Edo (now Tokyo) and often depicted theatrical scenes of wide-mouthed reptiles, dancing cats, writhing dragons and dismembered figures. Examples of this style in Japan Supernatural include Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Mitsukuni defies the skeleton spectre conjured up by Princess Takiyasha, 1845–46, where a giant skeleton heralds impending doom, and Toriyama Sekien’s Night procession of the hundred demons (Hyakki yakō zu), c1772–81, a humorous, sprawling tale of intermingling spirits and humans.

In addition to the ukiyo-e print, ghost paintings were also a popular art form, with many residents of Edo hanging them in the entrance of their homes as a way to scare off unwanted intruders. For Japan Supernatural, Fuyuko Matsui recreates ghost paintings in a contemporary context using the technique of nihonga, a traditional form of brush painting on paper or silk.

Focusing on female figures, Matsui views her intricate and violently graceful paintings as visual embodiments of trauma, loss and physical pain. “Matsui is influenced by medieval Buddhist paintings, old style ghost paintings and artists like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (also in Japan Supernatural), but she gives her own perspective, expressing her experiences as a woman currently living in Japan,” explains Eastburn. “She describes it beautifully as ‘the multitude of tiny pains that make up a life.’ It’s a very personal and feminist perspective.”

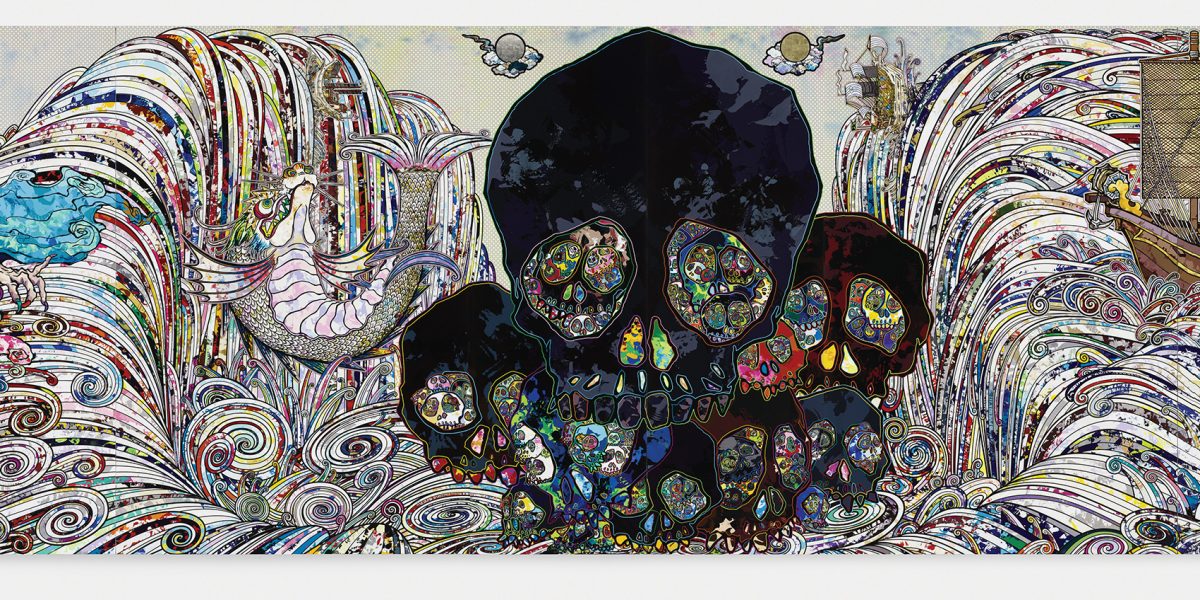

With bright colours, shiny surfaces and intense detail, contemporary artist Takashi Murakami blends the supernatural with real world events. Known for his frequent collaborations with fashion houses and high-profile musicians, Murakami’s monumental painting, In the land of the dead stepping on the tail of a rainbow, 2014 is a major component of Japan Supernatural. In order to accommodate its 25-metre width, the AGNSW have removed several walls to allow the painting’s swirling waves, dragons, ships and wrinkled spirits to be viewed uninterrupted.

Relating to the catastrophic effects of earthquakes and tsunamis in Japan, Murakami’s painting is so overwhelming with churning details, you can almost hear the roar of moving water.

More broadly, Japan Supernatural also explores Japonism and European fairytales, tracing how these influences have morphed into Japanese art, literature and film. Eastburn confirms that despite their ghoulish facades and otherworldly powers, monsters and ghosts will still continue to hold our fascination far into the future. “A hundred years ago, it was said humankind’s greatest invention was monsters. I believe this still rings true. This is how we tell our stories, this is how we work out who we are, how we work out what is good and bad – it’s all through monsters. They are a way to explain strange things.”

Japan Supernatural

Art Gallery of New South Wales

2 November — 8 March 2020

This article was originally published in the November/December 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.