Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

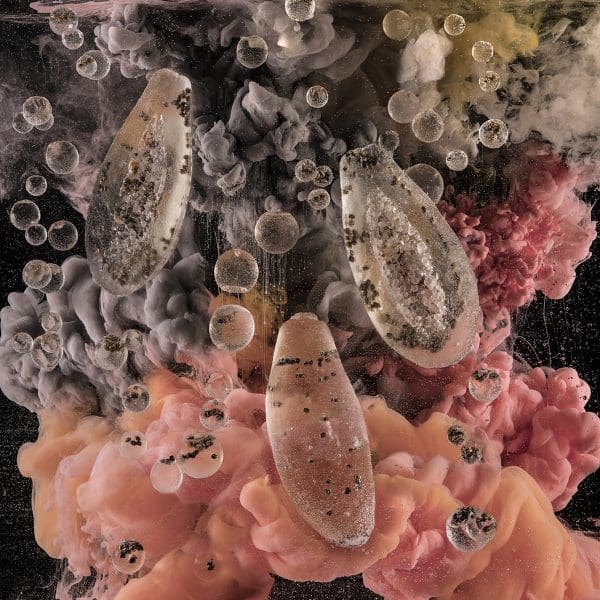

Janet Tavener, Sharp Velvet, 2018, ChromaLuxe on aluminium, edition of 10, 91 x 91 cm. Courtesy of the artist and MAY SPACE, Sydney.

Janet Tavener, Connovers Colossal, 2018, ChromaLuxe on aluminium, edition of 10, 91 x 91 cm. Courtesy of the artist and MAY SPACE, Sydney.

Janet Tavener, Preludio, 2018, ChromaLuxe on aluminium, edition of 10, 91 x 91 cm. Courtesy of the artist and MAY SPACE, Sydney.

Images are powerful. In 1972 a photograph taken by astronauts on the Apollo 17 mission, now known as The Blue Marble, altered forever the way we see our planet. Seen in the vast reaches of space, Earth suddenly appeared insignificantly small, fragile and vulnerable. The artificiality of political borders was revealed and the planet could be seen as a whole. This single image had a significant impact on burgeoning environmental awareness. As Ursula K. Heise put it in her 2008 book Sense of Place and Sense of Planet, “Set against a black background like a precious jewel in a case of velvet, the planet here appears as a single entity, united, limited, and delicately beautiful.” The lush photographic compositions in Sydney-based artist Janet Tavener’s solo show The Last Seed can trace their lineage to this stunning image.

But while the Apollo 17 astronauts rendered the macro small – Earth transformed into a perfect spherical gem – Tavener’s works achieve the opposite effect. In her striking artworks the micro is made massive, but no less beautiful. In The Last Seed frozen fruit and vegetables float alongside tiny seeds encased in balls of ice; together they resemble celestial bodies suspended in the infinite inky blackness of space. In fact, from a distance Tavener’s artworks resemble some of the more dramatic images captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope; all roiling clouds of coloured gas punctuated by pinprick stars. But Tavener’s subject matter couldn’t be more terrestrial: the bounty we reap from the dirt, when conditions are right.

It flooded in late May 2017; a casualty of what The Guardian newspaper reported was “the hottest ever recorded year”. Apparently the permafrost of the Arctic Circle is not so permanent after all. Less than a fortnight later, American President Donald Trump withdrew the US from the Paris climate accord, a UN initiative designed to mitigate the effects of greenhouse gas emissions. Mimicking the proverbial ostrich, Trump may hope that ignoring the climate crisis will make it go away. But for artists like Tavener putting your head in the sand is not an option.

Her jewel-like artworks serve to highlight just how precious and precarious life on earth is. It is not just the seeds stored in Norway that are vulnerable: all seeds, all plants and all animals worldwide are threatened by manmade climate change. If The Blue Marble asked us to look at the planet and see it differently – not as a resource to be exploited but as a gift to be treasured – Janet Tavener’s images in The Last Seed ask us to take a long hard look at ourselves and what we value.

Janet Tavener: The Last Seed was at May Space, Waterloo, Sydney from 27 June to 21 July.