Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

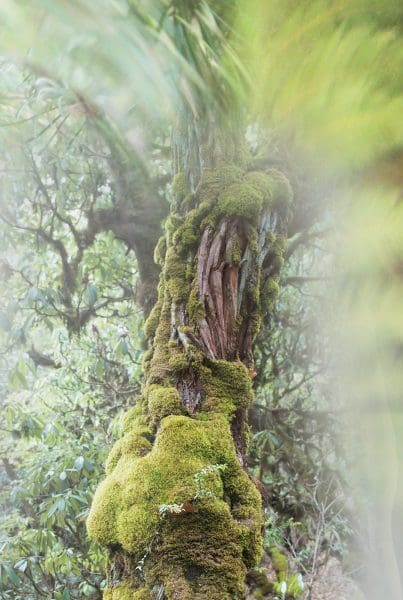

For three decades Janet Laurence has been lauded for her simultaneously conceptual but also emotive approach to nature. In our interview she talks about being a female artist dealing with nature, and what it means to create ecological art in a time of great environmental threat.

Tiarney Miekus: Have you always seen art as a response to the natural world, or did your initial interest in art start from a different place?

Janet Laurence: They both began individually but they came together quite quickly, funnily enough. In my early art training, I was living in Europe and it made me really consider our relationship to the land and the elements of nature in both Europe and Australia, and the incredible difference of being in Europe with the environment. It made me want to explore the nature of a particular place, so [nature] entered into my art in this way. Initially my art had evolved through an interest in elemental matter and alchemy. There were a whole lot of reasons for that; one was a feminist reason, another was a love of the process of things evolving and changing in time, and the being of matter and its transformation. I wanted to have this more conceptual overview of looking at how we dealt with our environment, nature and landscape. Somehow, that made me want to look inside the landscape rather than at the landscape in a picturesque way.

TM: I noticed your first solo show was in 1981 when you were in your early thirties. It made me wonder if there was something else you were doing in your twenties, or was being an artist the only goal?

JL: I was doing art on the side of other things like studying medicine, and then going and living overseas and doing a lot of different jobs. I went to art school in Italy when I was quite young and was then living in the country there [in Italy] in a very hand-to-mouth way, growing all my vegetables. Somehow, we never worried about time in those days, nor careers!

I always wanted to make art, but I really wasn’t attached to any art world. My making of art was very much attached to my way of life, and that allowed me to delve into a lot of ideas.

TM: Were your family artistically minded?

JL: No, not at all. And that’s why they never let me study art. In those days there were very few women artists you could look to in Australia, and it was assumed if you were studying art you’d be doing commercial art. It was by being in Europe that I explored much more of an art world, and I realised the difference of being in Australia with our young country that’s still trying to find its way on this land, as compared to the Europeans who are so embedded in the history of being on that place. It led me, when I came home to Australia, to get a job with the Flying Arts School, and flying around northern New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory to do art classes. It was connected to a university in Brisbane, but was for people who were very isolated and wanted to study art.

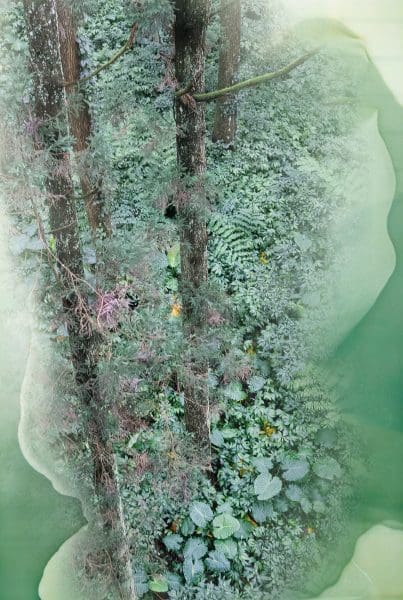

The extraordinary thing was most of them were landscape painters, but they weren’t really engaging with that landscape, nor were the farmers listening to the land. It was the whole story of how we colonised this place and how our art followed the same pattern. We just attached other ideas onto art dealing with the Australian landscape. That made want to look inside the being of the Australian landscape as compared to just making images that look like a European painting of it.

TM: That’s interesting, because the artists and writers that you often cite as being influential, people like Robert Smithson, Joseph Beuys, Gaston Bachelard and W. G. Sebald, are all concerned with nature, but how nature is subjective, historical, conceptual and psychological. It feels like a method you follow.

JL: Exactly. That was a way of entering into the landscape. That’s why alchemy was amazing knowledge to have as a process for entering nature: to watch the transformation of things and to think about that transformation, and then to give that meaning. When I was in art school in America, I gravitated to the more conceptual artists too, and I still am so engaged by that practice, but I seem to have ended up a little away from that—and I think it’s the nature of being here in Australia, too, and not living such an intense dialogue like that.

TM: An interviewer once asked you, “Your works do set out to communicate something, don’t they?” And you said yes, but you didn’t say what those things are.

JL: What I’m trying to communicate is not necessarily one thing, but more a wonder of nature. A lot of the work is dealing with fragility and loss, particularly more recently, and so I’m also often wanting to communicate care and empathy.

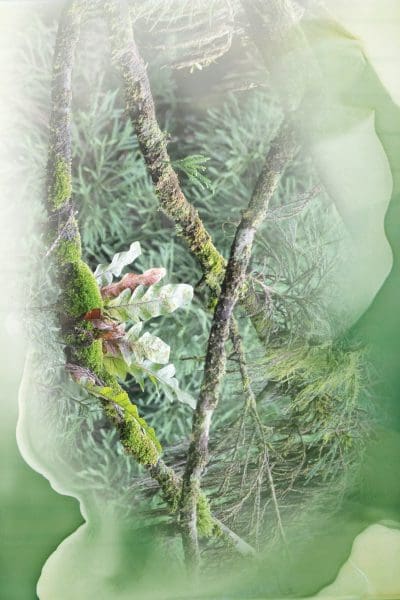

TM: Do you think it’s interesting that we’re so largely disconnected from nature that we go to places like art galleries to get that experience of the natural world?

JL: It’s funny that we do that, isn’t it? It’s such a shame. But I hope that by going to a gallery to get that experience, it can open you up to the real world. The gallery can give you a focus and a lens to look through, and maybe even understand something, and can bring it to your attention. Often in the bigger world, people aren’t looking. When you make an inquiry into a gallery or museum, you close up the whole world, in a way. You enter into that space, and having complete focus like that can heighten your senses.

TM: I’m curious about the experience of being a female artist and creating works that deal with nature, especially when men have often been seen as quite heroic in this field. Has gender affected how you’ve been received as an artist?

JL: Yes. I think it’s true that women painters were relegated to doing still lifes, while the main painters recording the landscape, or so-called recording the landscape, were men. But I also think there is another approach where women will look sideways and inside, perhaps more than the men who are still looking through the tradition of the more heroic image. I felt very free as a woman to work sideways, and I often thought of alchemy as the side thing from the true science and true chemistry of the world—a kind of meta-science.

The funniest thing is that my first review ever, which I’ve never forgotten, said, “Janet Laurence deals with nature and the dark side of life, and this is not a place where women should be.” What were women meant to be doing? Painting domestic life? And still, funnily enough, being a woman going through the 80s and feminism at that time, there were very few women who were engaging with the natural world. There were people like Bonita Ely and Rosalie Gascoigne, and they were heroes to me because so many women were talking about their constructed feminist lives—and if you look at the history of feminist art, that was all to do with identifying as a woman— but I just side-stepped that. I’m very removed from my work in some ways. I’m there, but I’m removed. I never consciously introduce myself into it, which so many feminists did.

TM: Does it feel strange that as your success increases, the very subject matter of your art becomes more endangered and fraught?

JL: Yes, it’s funny. People say of my work, “Oh, it’s so timely.” And you feel like saying, “Well, I’ve been doing it for 30 years!” But I think the field of art is a little conservative in its approach to these things. Climate change has taken a long time to enter art. And one of the reasons is—let’s face it—look who’s backed the art world. It’s a lot of fossil fuel money. It’s very difficult, but I think it makes me more passionate about doing stuff because I think, “God, we really got to this terrible state of emergency.”

TM: Do you ever have moments of crisis where you wonder what art can do for environmental threat?

JL: Yes, of course. I think, “How much are we heard?” But it’s not going to stop me because I think it’s better to act than to feel resigned and give up. I also feel that my art is partnered much more with actions, like climate change actions. But I don’t really want my art to be protest art. I just feel we have to choose whatever means we have to speak and act. And I think in doing that, it gives you a space for hope, you know? Small responses are often really important.

Tree Story

Monash University Museum of Art

6 February—10 April

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now

National Gallery of Australia

14 November 2020—4 July

This article was originally published in the March/April 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.