Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Janet Dawson, The origin of the Milky Way, 1964. Photograph by Reg Ryan.

Anne Dangar, Un composition, pochoir, 1936, drawing in brush and gouache. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Purchased 2002.

Grace Crowley, Painting,1951, oil on composition board. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Purchased 1969.

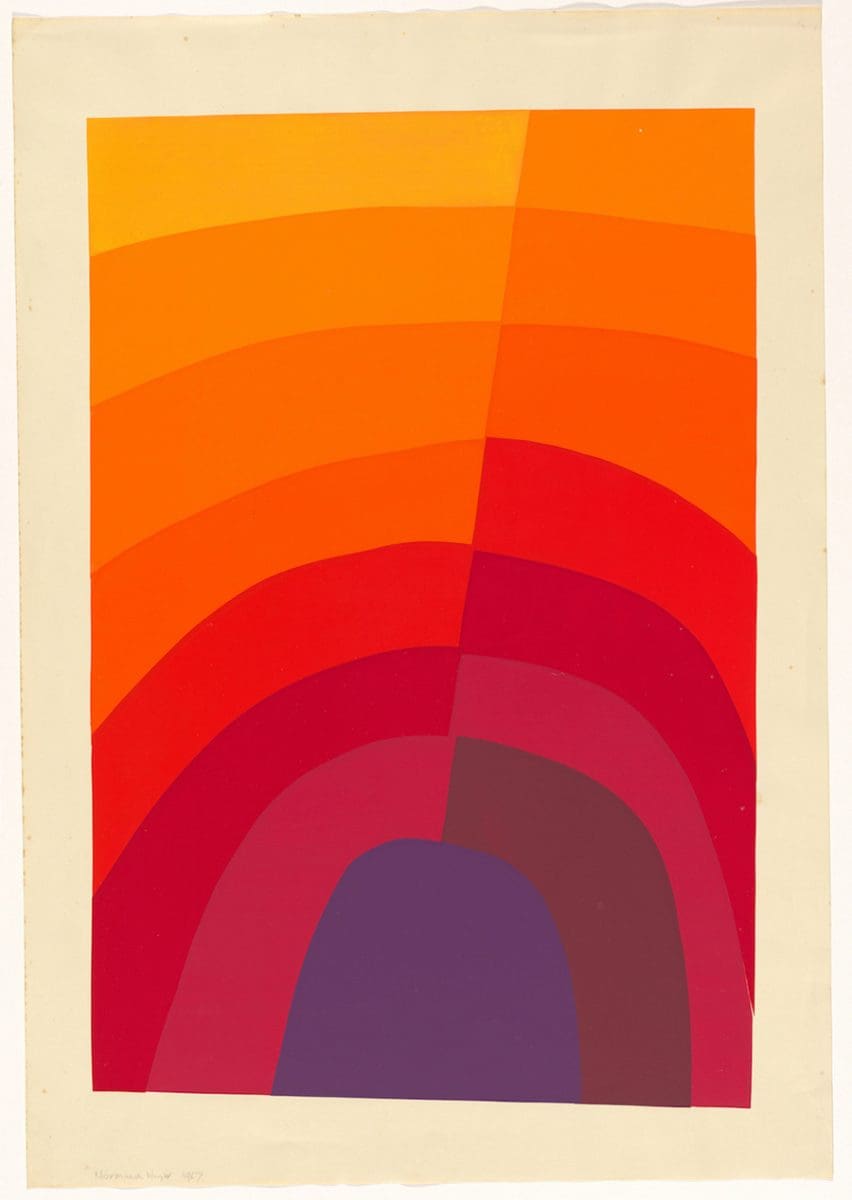

Normana Wight, Untitled – purple to yellow diagonal, 1967, screenprint, printed in colour inks, from multiple stencils. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Gift of the artist 2013. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program.

Senior Australian artist Janet Dawson is one of 38 artists included in the exhibition, Abstraction: celebrating Australian women abstract artists. Drawn from the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia, this survey is a long overdue antidote to a male-dominated history of abstract art. Dawson was one of only three women to show in the influential 1968 exhibition The Field, which will be restaged in 2018 at the National Gallery of Victoria for its 50th anniversary. Rebecca Gallo spoke with Dawson about her impressions of these major shows, her experience in a male-dominated art world, and the beauty and pleasure of good abstract art.

Rebecca Gallo: Your work Study for lighthouse, 1968, which is featured in Abstraction: celebrating Australian women abstract artists, was wrapped in a blanket for over 40 years after its initial showing. Can you tell me a bit about this work?

Janet Dawson: I did a series of panels called Lighthouse, and this particular one I was very fond of. The thing about a lighthouse is that it sends out light into the world, but the lighthouse itself is dark. So I represented the lighthouse by a central dark square, and one ray of light spreads out and actually distorts that end of the panel. I had it wrapped up in my store in Binalong, NSW, where I lived with my husband for 40 odd years, and occasionally I’d have a look at it and see if it was alright, and I’d think, ‘that’s rather a good work really!’

RG: What was it like to bring it out of storage?

JD: A lot of paintings go to sleep and get very miserable in storage. You bring them out, and they really look, oddly enough, miserable and dull for some days. And then they start to come alive again; if it’s a good painting.

Storage is actually a good way to get an objective view of a work, and having had so many works in store all these years, I find that some keep their freshness, and some don’t. It’s like a little treasure trove.

RG: What was your experience of being included in The Field in 1968?

JD: I had been working at Gallery A [in Melbourne]…one of the few galleries that was showing non-objective, modernist and colour field work. We were right in the middle of it all. The Field was a very narrow choice: colour field, very severely abstract work. There were a lot of young, talented and ambitious people around, all trying to extend the range of modernism in all sorts of ways. Some stayed with colour field, which was eligible for The Field, and others were pushing into different areas. I just slid in with my work that was a tonally modulated surface. It probably looked a bit different from the others.

RG: What do you think about The Field Revisited, scheduled for the 50th anniversary next year?

JD: I think both Abstraction: celebrating Australian women abstract artists and the remake of The Field are going to be very strong presences in the art world, and cause quite a lot of excitement.

Over the last few years, there has been a fashion for very gloppy, sludgy sort of paintwork, and I’ve found it very depressing. I think this will be a very fine corrective which says, ‘Here is the most beautiful thing you can work with: space, colour and light.’ Now, what else do you want, really?

I think the public will love it too, because they are now more used to modernism and to colour than they were when The Field first came out. And I think women are particularly good at colour. I don’t wish to make distinctions in this way, but I think there is a general theme of good colourists in women’s art.

RG: What has been your experience of working in a male-dominated art world, particularly in the 1960s?

JD: I’ve always been very lucky and I’ve had very little discrimination because of my gender. But there was certainly discrimination. It must be difficult to keep going if one feels there is this ignorance or push against one’s work because of gender. I think it’s very wrong. I’ve been lucky enough not to suffer from it, but other women I know definitely have.

Of course there were only three women in The Field: myself, Wendy Paramor who died shortly after, and Normana Wight, who has had to remake her work, which is probably going to be a very pleasing thing for her. Her painting from The Field was so enormous in her studio that finally she just cut it up. It’s a magnificent work, and I’m really looking forward to seeing it again.

RG: What are you most looking forward to seeing in Abstraction: celebrating Australian women abstract artists?

JD: When the curator Lara Nicholls gave me the images for the works in this show, I was very deeply moved, particularly by the early work by the women artists of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s.

Their work has a classical beauty and formal, constructive power which sets the standard for the exhibition. Works by artists like Dorrit Black and Grace Crowley were based on a very solid knowledge of Cubism, and they could work through it to create very powerful and beautiful paintings. They had such a strong grasp of their subject, they really knew what they were doing, and created very strong constructivist paintings. This show will bring all these artists back into the public eye again.

RG: You are well known for both your abstract and figurative work. How do you move between the two?

JD: I have an animistic turn of mind, so I’m always seeing faces in the shadows and all that sort of thing. I fell back in love with the world when I went and did scientific drawing, and I thought my calling was to really examine the natural world.

So my work has been what I call adulterated abstraction, because there is nearly always a figure or an animistic image behind what I do. I can’t help that, it’s just my nature. After struggling a bit in the days of hard abstraction, I thought, this is not me, really.

RG: What can abstract art do that figuration can’t?

JD: A good abstract work is a great joy. The feeling you have when you are looking at a cloud, and your mind starts to attach itself to the image, and your whole self comes out and sort of sits there between you and the cloud. There is this enormously simple and healing sort of rapport, and I think that happens with good abstract painting too. If you can empty your mind of chatter, and just live with the work for a few minutes, you find this enormous release into a mode of thought that is beyond speech.

I had a conversation with gallerist Charles Nodrum about abstraction, and he was saying that a really good non-objective painting can settle the mind and heart in a way that other paintings can’t. You live with it and you think, that’s right. If you can get that rightness, then the work will just sing, always.

Abstraction: celebrating Australian women abstract artists

Geelong Gallery

25 February – 7 May

Newcastle Art Gallery

21 May – 23 July

Cairns Regional Gallery

15 September – 24 November

Tweed Regional Gallery

2 March – 27 May 2018

QUT Art Museum

1 June –26 August 2018

The Field Revisited

National Gallery of Victoria

May 2018