In Janenne Eaton’s art lies an implicit critique of our over-reliance on digital technology, a musing on the collision of our physical and virtual worlds.

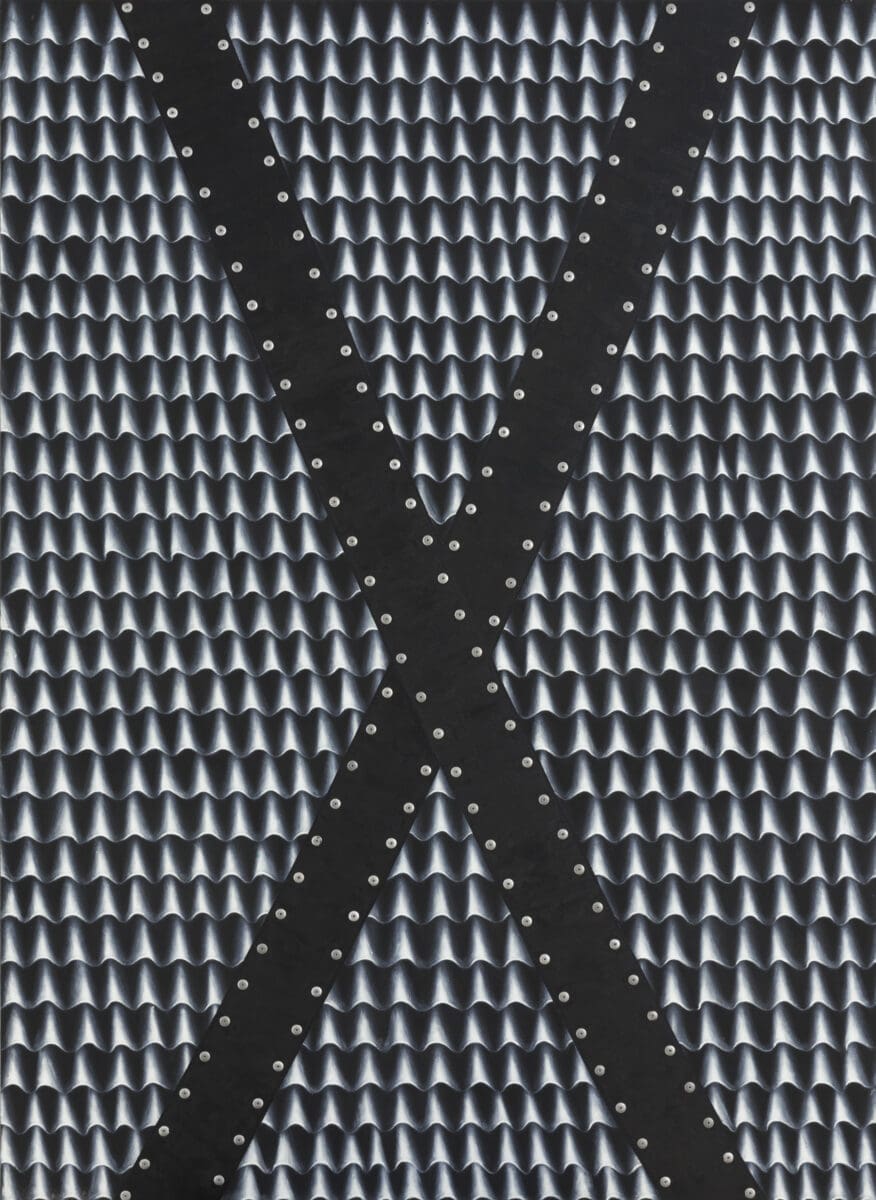

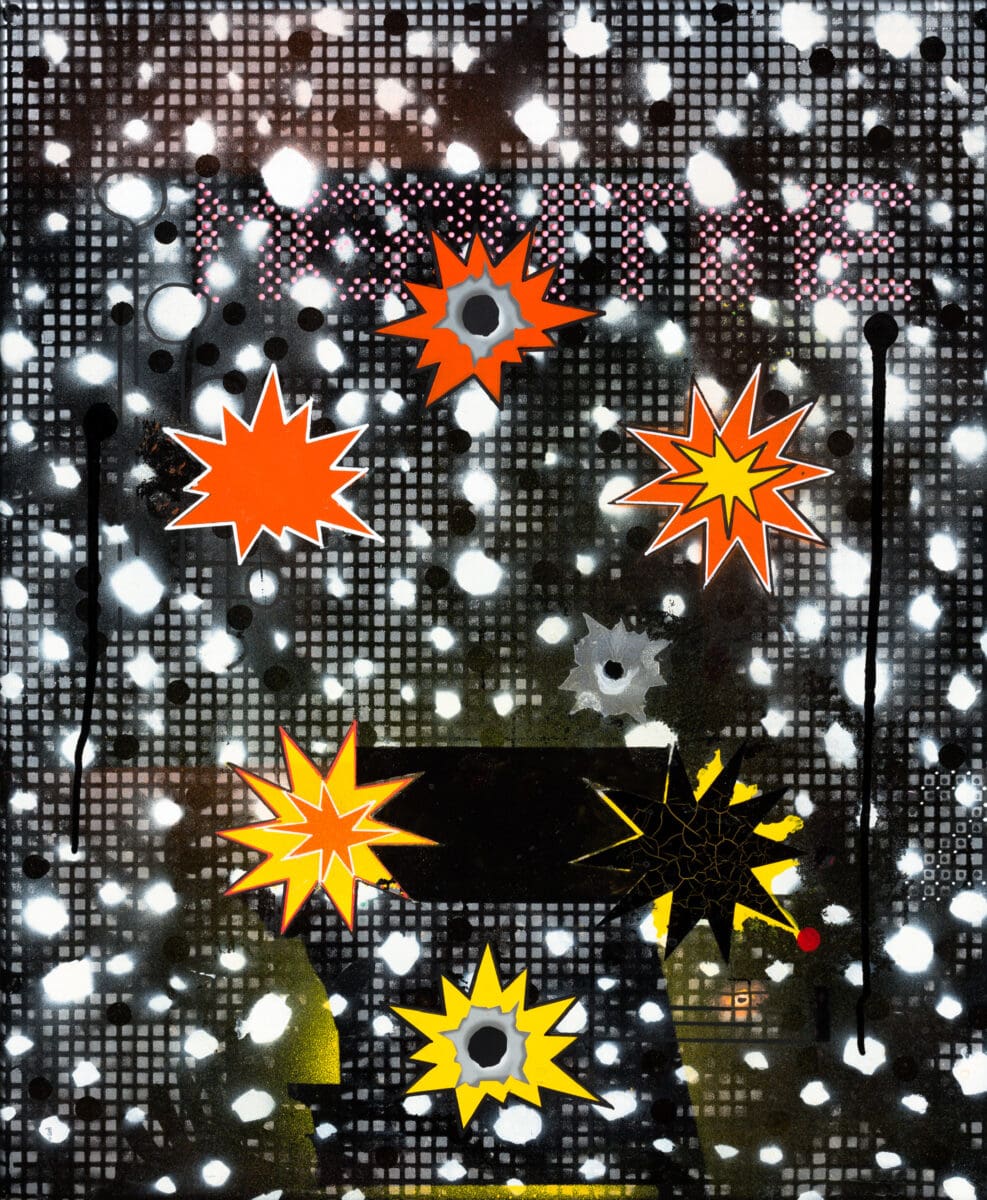

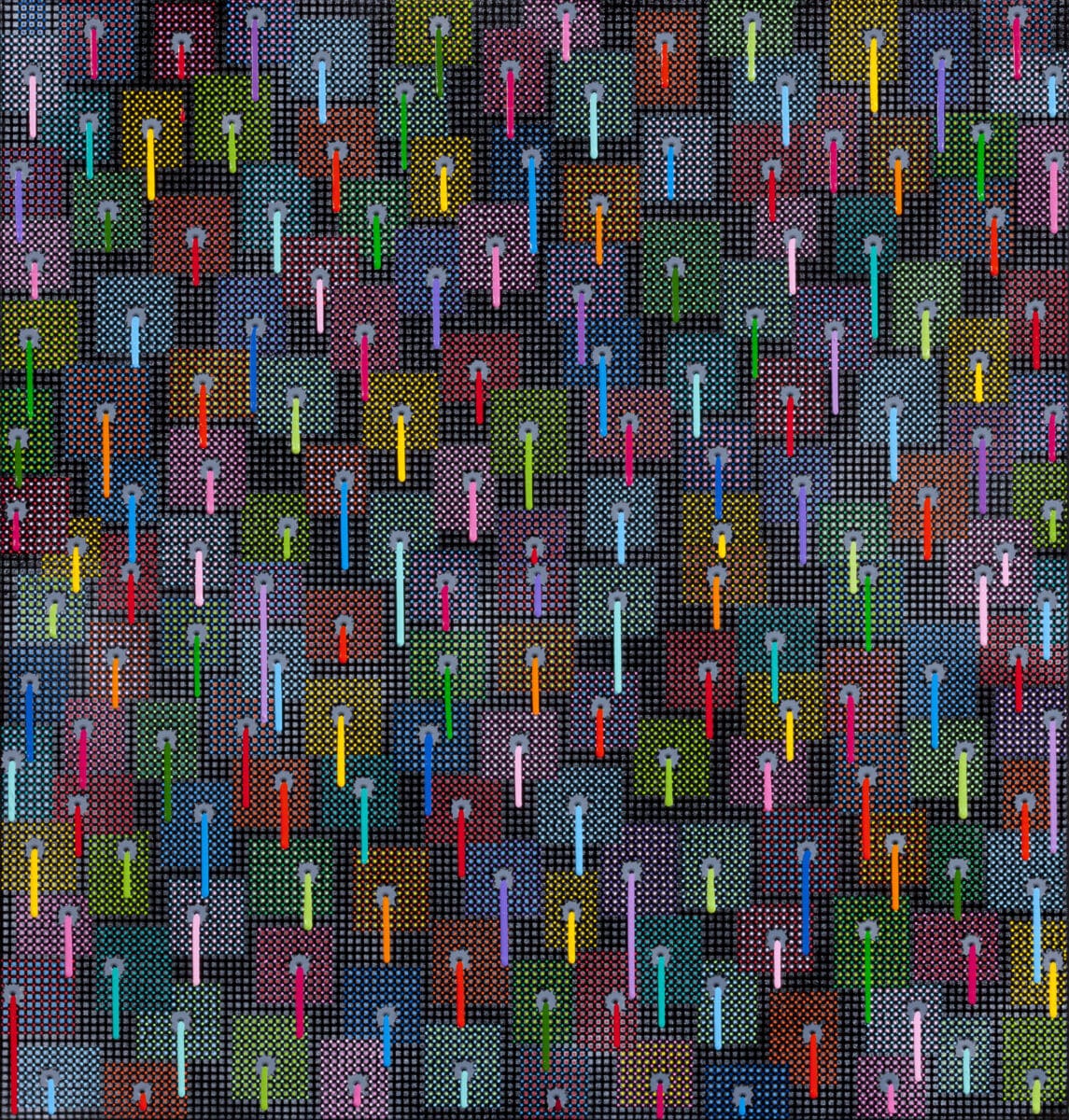

Using a fine grid structure to represent our ubiquitous LED screens, her paintings and installations feature kinetic points of light that give a sense of flux to her often cosmos-like deep black surface plane.

Having used traditional canvas for most of her career, a decade ago the now 74-year-old Melbourne artist began also using high-impact polystyrene (HIPS) to reflect the viewer back to them, implicating her audiences in the bigger picture of this global surveillance society.

In her St Kilda studio, flanked by community vegetable and flower gardens, Eaton has just finished one such work about technology occupying outer space, again creating on this lightweight thermoplastic material.

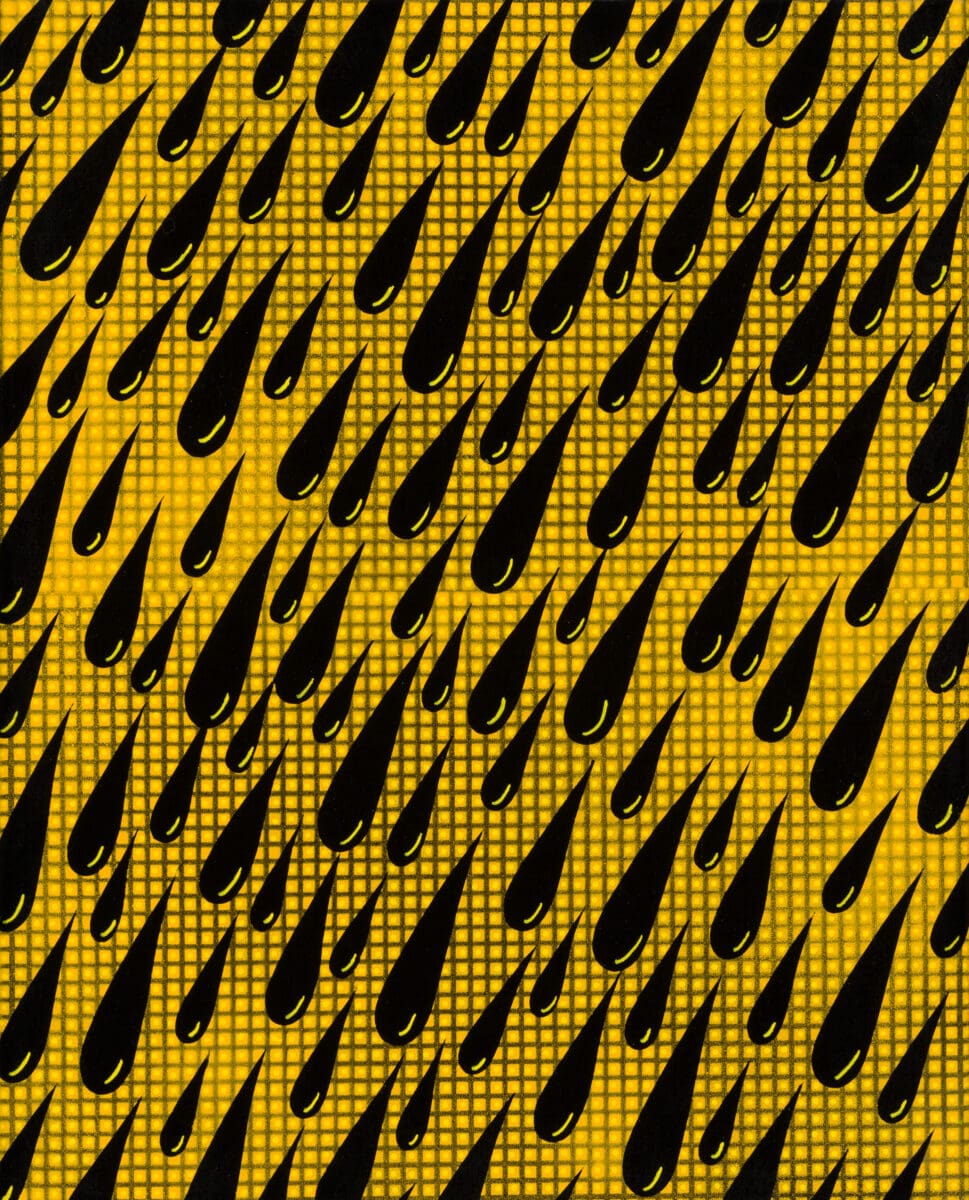

This new piece, Billabong, building on an earlier work of that name, references drones and planetary explosions, and is designed to complement the curved walls of a particular room at the Geelong Gallery for her upcoming career survey.

Is she creating a place to contemplate the state of civilisation? “That’s exactly right, yes. It’s a very dynamic and vivid and complex and disturbing space,” she laughs.

While Eaton is critiquing the way humans mediate so much of their lives though screens, she has long been fascinated by how “disembodied” humans interface with the cosmos, “being online across the globe, in contrast to our physical and material world, everything we know and touch and breathe.”

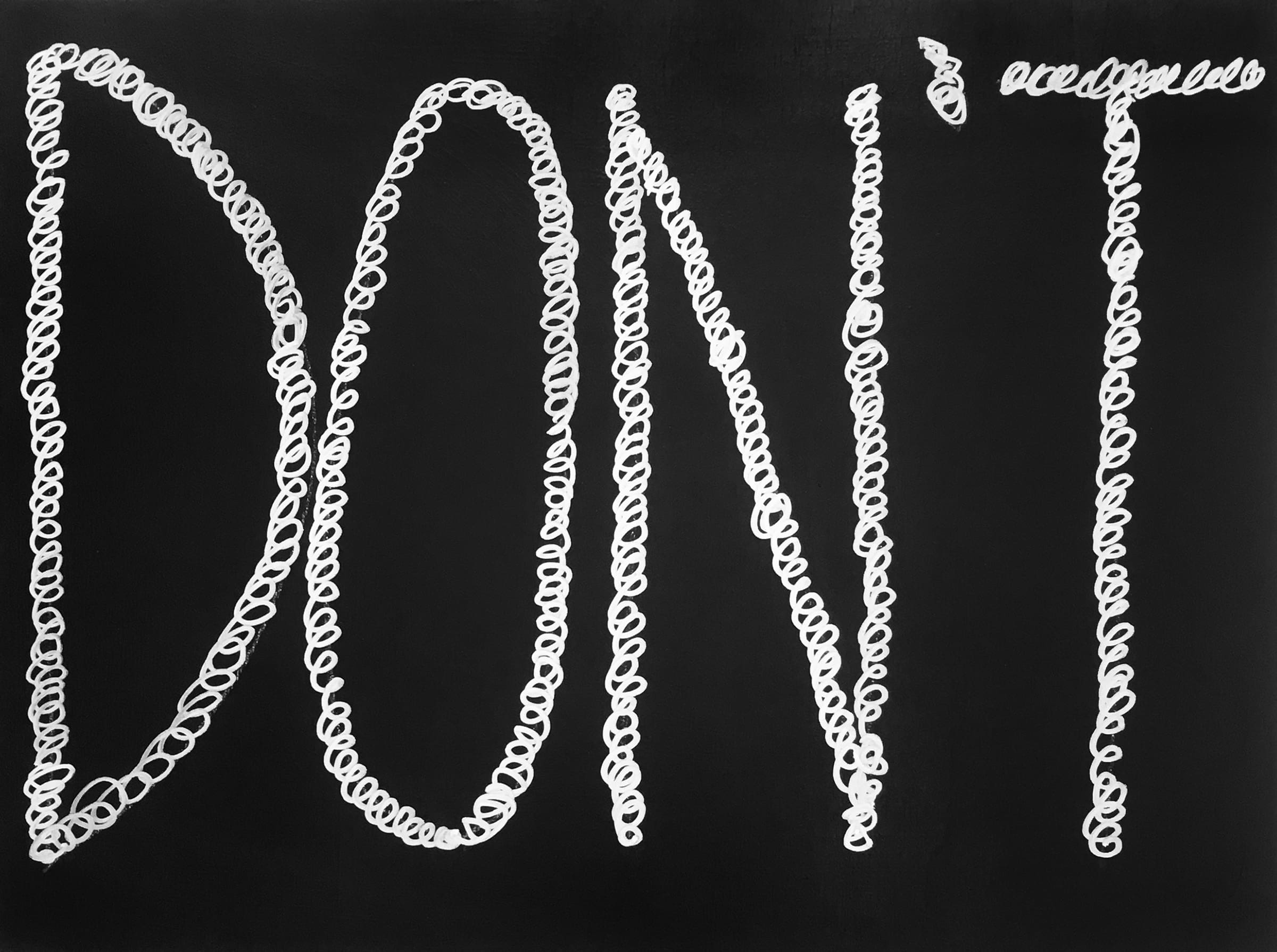

Her text in large letters in oils and enamel are foreboding about the future, as though dredged from the dreams of a fitful sleep: Don’t, Pause, and Keep Clear. At the heart of her works is a deep-seated critique of how the present Anthropocene and consumerism have impacted the climate and the environment.

Eaton dates these concerns to her childhood and teenage years in the 1950s and 60s, growing up in Springvale South, south-east of Melbourne, where her carpenter father built their home among the gum trees, long before the area became a densely populated suburb.

Deep sand pits were soon dug directly opposite the family home in Clarke Road to supply the house building boom, destroying market gardens, an environmental extraction that would have a big impact on Eaton’s artistic preoccupations. Later, the site became a huge rubbish tip (although the 47-hectare landfill area has since been rehabilitated and is now earmarked for a renewable energy hub, including a solar farm).

Eaton has always seen herself as a landscape painter, but she gained profound inspiration from archaeology between earning her Diploma in Art & Design from Caulfield Institute of Technology in 1970 and becoming head of the painting program at the Victorian College of the Arts from 1999 to 2011.

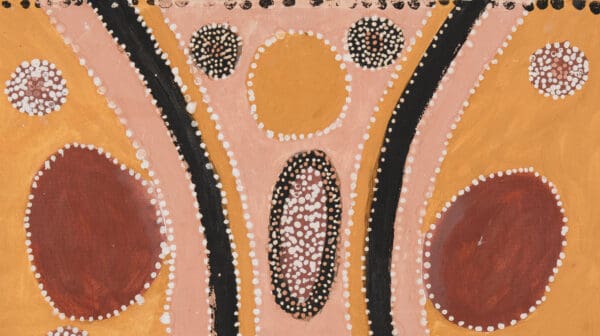

In the 1970s and 80s, Eaton would accompany her archaeologist partner, William Ferguson, on archaeology digs, beginning with the famous Devil’s Lair dig on Noongar Country in the south-west of Western Australia. In this cave, thousands of artefacts were found, including bone points and bone beads and animal and plant remains.

“I have always been interested in the way humans adapt and what they leave behind,” she says. “I used to draw the artefacts for various publications, I learnt to draw [those] from Charles Dortch, the archaeologist who was the central figure in the Devil’s Lair excavations.”

Eaton and Ferguson moved to Canberra, where Eaton began studying art history and philosophy at the Australian National University, but she hated the latter, so she swapped to art history and archaeology. She went to more archaeological digs, now on Australia’s east coast.

Yet it was the night sky during those first digs, particularly in Western Australia, that would influence Eaton the most during those occasions. “We did some trips up into the desert regions, up around Meekatharra and Murchison [in the mid-west], and one of the most marvellous experiences was the nights,” she recalls.

“You’d think it would just be filled with stars, and often it wasn’t. Often, the black just seemed completely empty and there wasn’t a sound, not even of an insect out there. The power of that experience, the swallowing quality of that black, engulfing, endless vision, was just beautiful, and very effecting, really. I think it did influence my work, but it’s all osmotic—all these experiences, they sort of seep in.”

Janenne Eaton: Lines of Sight—Frame and Horizon

Geelong Gallery

24 May—17 August