Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Jan Senbergs, Altered Parliament House, 1976, oil and screenprint on canvas, 182.5 x 243.5 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. © Jan Sensbergs.

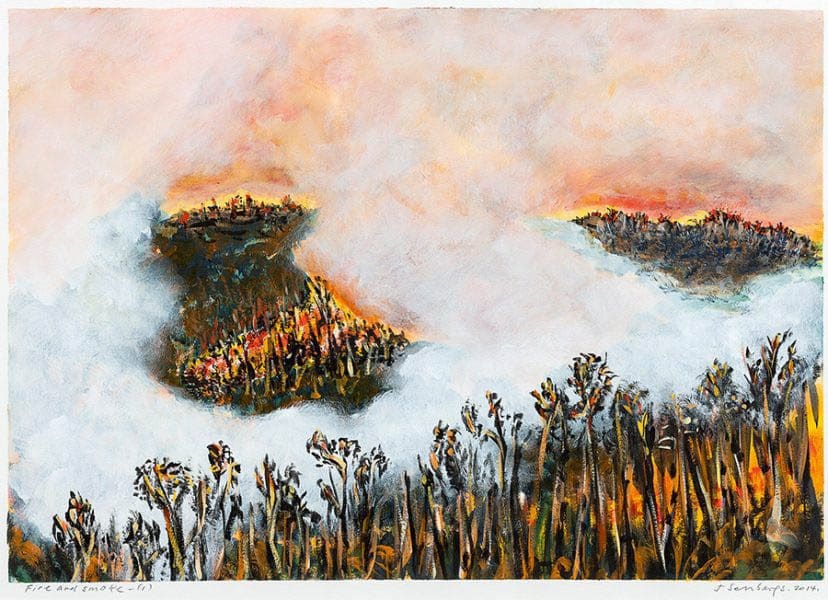

Jan Senbergs, born Latvia 1939, arrived Australia 1950, Fire and smoke 1, 2014, synthetic polymer paint on paper, 48.0 x 70.0 cm (sheet). Private collection, Melbourne, © Jan Senbergs. Image courtesy Niagara Galleries, Melbourne

Jan Senbergs, born Latvia 1939, arrived Australia 1950, Head, 1963, colour screenprint on paper, artist’s proof, edition of 10, 42.4 x 35.2 cm (image and sheet). Courtesy of the artist and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne. © Jan Senbergs.

Jan Senbergs, born Latvia 1939, arrived Australia 1950, Landfall, 1990, 1994, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 198.0 x 244.0 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne. © Jan Senbergs.

Jan Senbergs, born Latvia 1939, arrived Australia 1950, The whipper, 1961, enamel paint on composition board, 183.0 x 122.0 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, © Jan Senbergs.

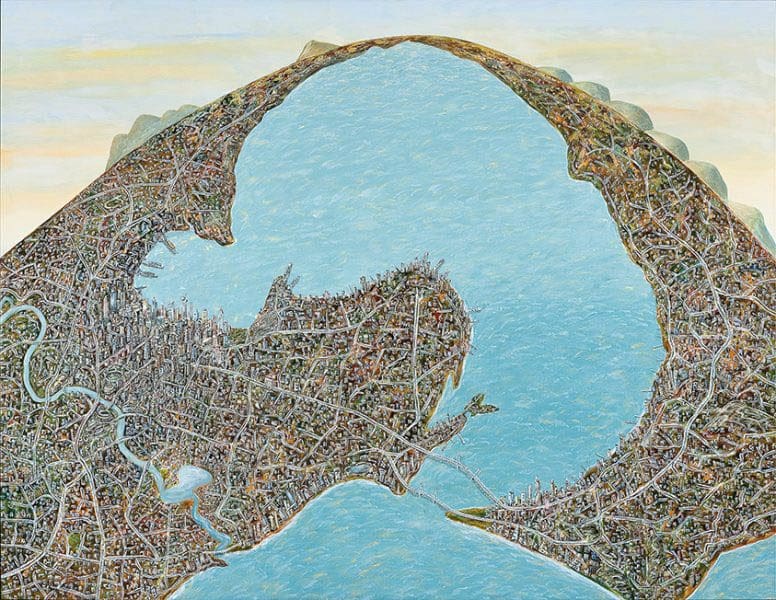

Jan Senbergs, born Latvia 1939, arrived Australia 1950, Geelong Capriccio (if Geelong were settled instead of Melbourne), 2010, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 197.0 x 255.0 cm. Deakin University Art Collection, © Jan Senbergs. Image courtesy Niagara Galleries, Melbourne.

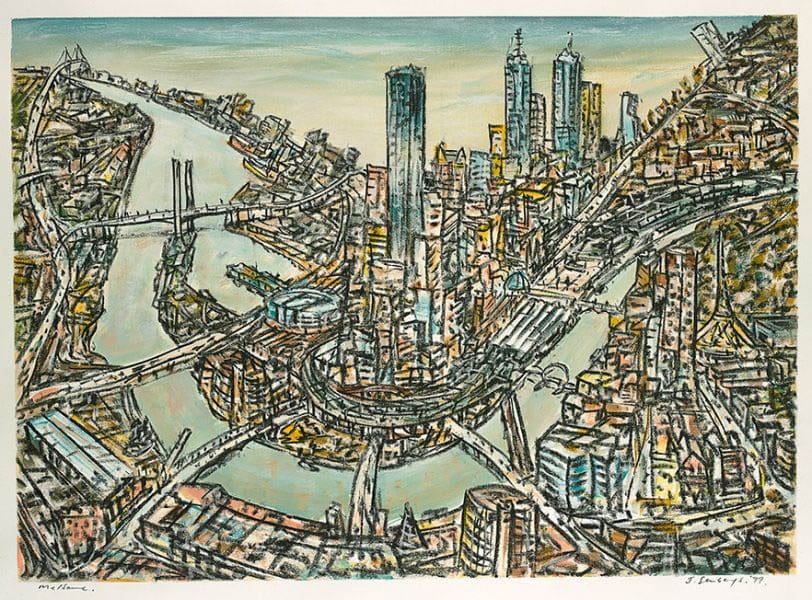

Jan Senbergs, born Latvia 1939, arrived Australia 1950, Melbourne 1998–99, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 183.0 x 274.0 cm, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of the Gualtiero Vaccari Foundation in recognition of services provided by the State Library to the Italian Community; 1999 © Jan Senbergs.

There’s a wall in Jan Senberg’s studio that’s covered in hundreds of images, all neatly arrayed in a salon-style grid, affixed in place by round white pins. Any sense of order ends there.

Clippings of quotes, photographs of animals, aerial maps, cartoons and a ‘Greetings from Dandenong’ postcard abut important works of art. One photograph inexplicably depicts Tsar Nicholas II, Karl Marx and the two Vladimirs – Lenin and Putin – setting their differences aside to pose with a tourist. They’re wax models, he explains.

Senbergs calls this his Indulgence Wall, though to say it’s an indulgence is ungenerous. If anything, it’s an example of Senberg’s wide range of interests and diversions, all of which goes to explain the consistent inconsistency of his practice.

From his first exhibition in 1960 to now, Senberg’s career has been marked by many shifts of style and medium, borne of anything from a trip overseas to an interesting book he happened to read.

Through it all, he has displayed a refusal to bend to the wax and wane of artistic trends and movements. This is neither stubbornness nor restlessness; more than anything, it’s risk-taking.

“It’s just like being a gambler,” he says. “You have your good moments, you have your bad moments. That’s the way it goes.”

All in all, it seems Senbergs placed a good set of bets. In March, the National Gallery of Victoria is hosting a retrospective of the artist’s career. At the same time, Niagara Galleries will be presenting a solo show of Senberg’s drawings – a central part in his practice now, but at its inception yet another gamble.

“I didn’t think I could draw,” says Senbergs. Born in Latvia in 1939, he arrived in Australia at the age of 10 having fled the horrors of the Second World War. He completed an apprenticeship in silk-screen printing – a second choice. “I tried to get into the art school at that time, but I couldn’t. I didn’t qualify.”

“Not having come straight out of the art school was certainly at first rather intimidating, because when you saw the characters who came out of art school they seemed to be much more self-assured than I was.”

This didn’t hold him back. In 1996 Senbergs was awarded the Helena Rubinstein Travelling Art Scholarship and and by 1973 he was representing Australia at the Sao Paulo Biennale in Brazil. His large mural for the High Court of Australia building, commissioned for its opening in 1980, remains there to this day.

“The thing about confidence is, you gain confidence after a while as you go along in your painting and your ability and your techniques and so on. But there’s always still a thing of starting something new, working out an idea, working out how a painting has to first of all be a painting.”

Just as it’s hard to find an organising principle underlying his so-called Indulgence Wall, it’s similarly difficult to distill his practice into a single, overarching pursuit. A more useful approach would involve considering the pursuit itself and the energy Senbergs pours into it.

“When I begin a series,” he explains, “I always go to great lengths to read a lot and try to find out as much as I can about the history of a place. Once you start reading that you have a better understanding of the place and then you start to paint the place and then you paint from what you know about it rather than what you see in front of you directly in one hit.”

In this light, the snappy title of his NGV show, Observation–Imagination, is a telling choice. Though both observation and imagination play a role in his practice, Senbergs never wholly relies on either on its own. His surrealist sensibility, while strong, isn’t an unmoored wandering, guided as it is by extensive research and a mental Indulgence Wall of various interests.

On another wall in his studio, Senbergs has pasted a piece of paper with a serendipitously found quote scribbled on it. Attributed to artist Thornton Dial, it reads “Art ain’t about paint – it ain’t about canvas – it’s about ideas. I have found how to get ideas out and I won’t stop – I got ten thousand left.”

At the time of writing, Senbergs is still trying to work out with the NGV a way to display the quote, a favourite, in the exhibition. “They might use my handwriting and then blow it up [on a wall],” he suggests. If not, that leaves another 9,999 ideas to try.

Observation–Imagination

National Gallery of Victoria

18 March – June

Drawings

Niagara Galleries

1 March – 2 April