Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

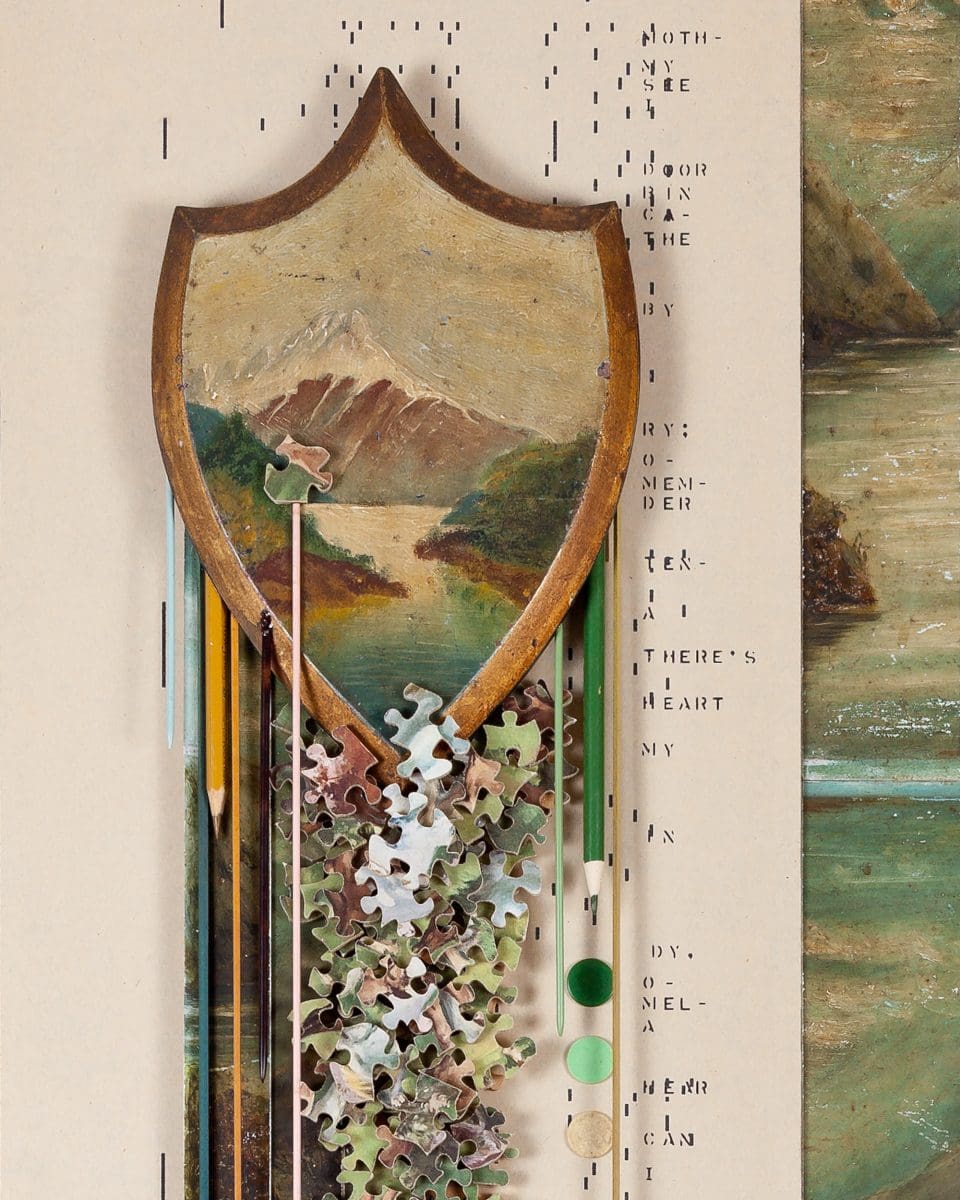

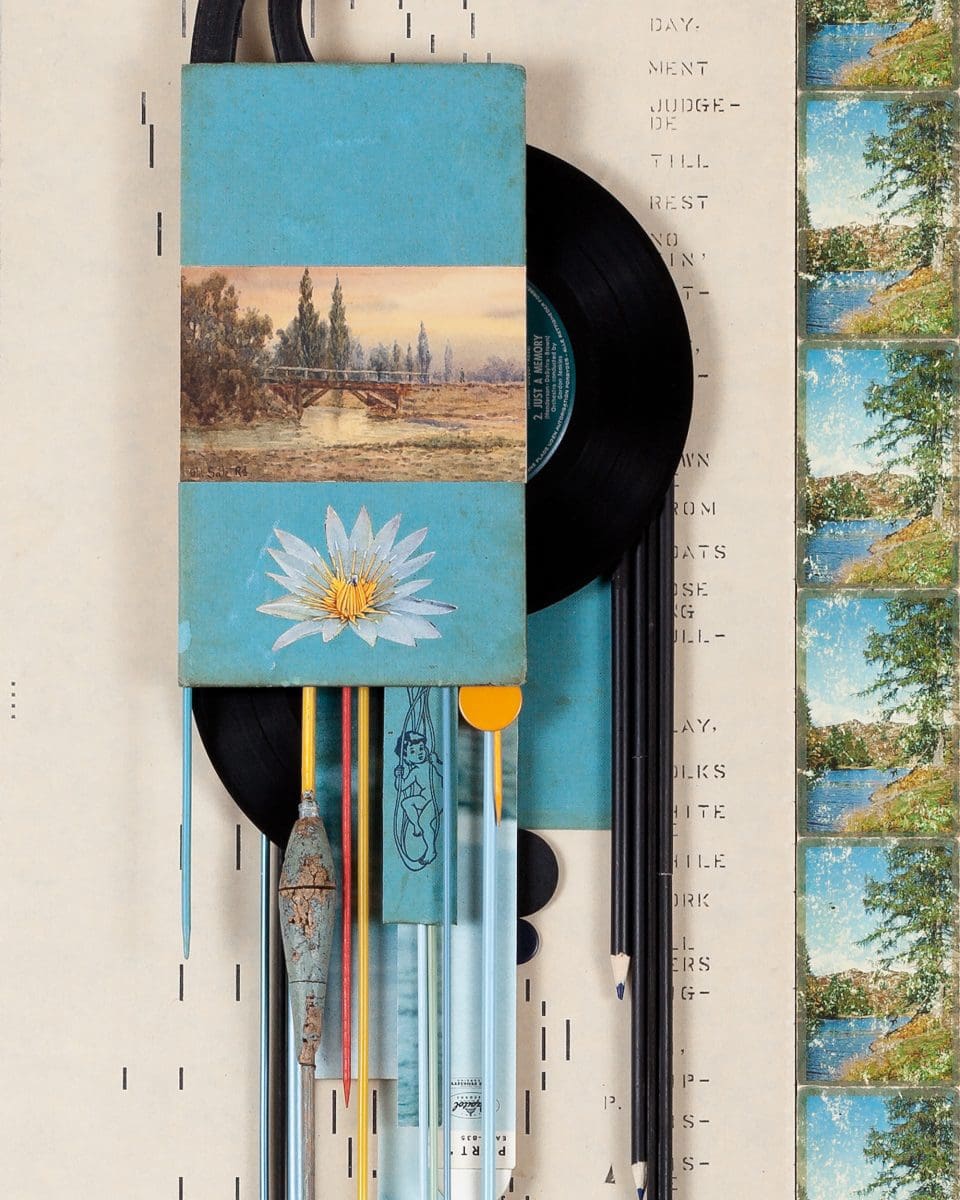

James Powditch’s new exhibition Codakhrome explores the fragility of memory. In his slender mixed-media assemblage My room, 2019, flowers fragment into pencils and toys that trail away like a comet. In another, a landscape breaks into jigsaw pieces. “I wanted it, in a three-dimensional sense, to dissolve,” he says.

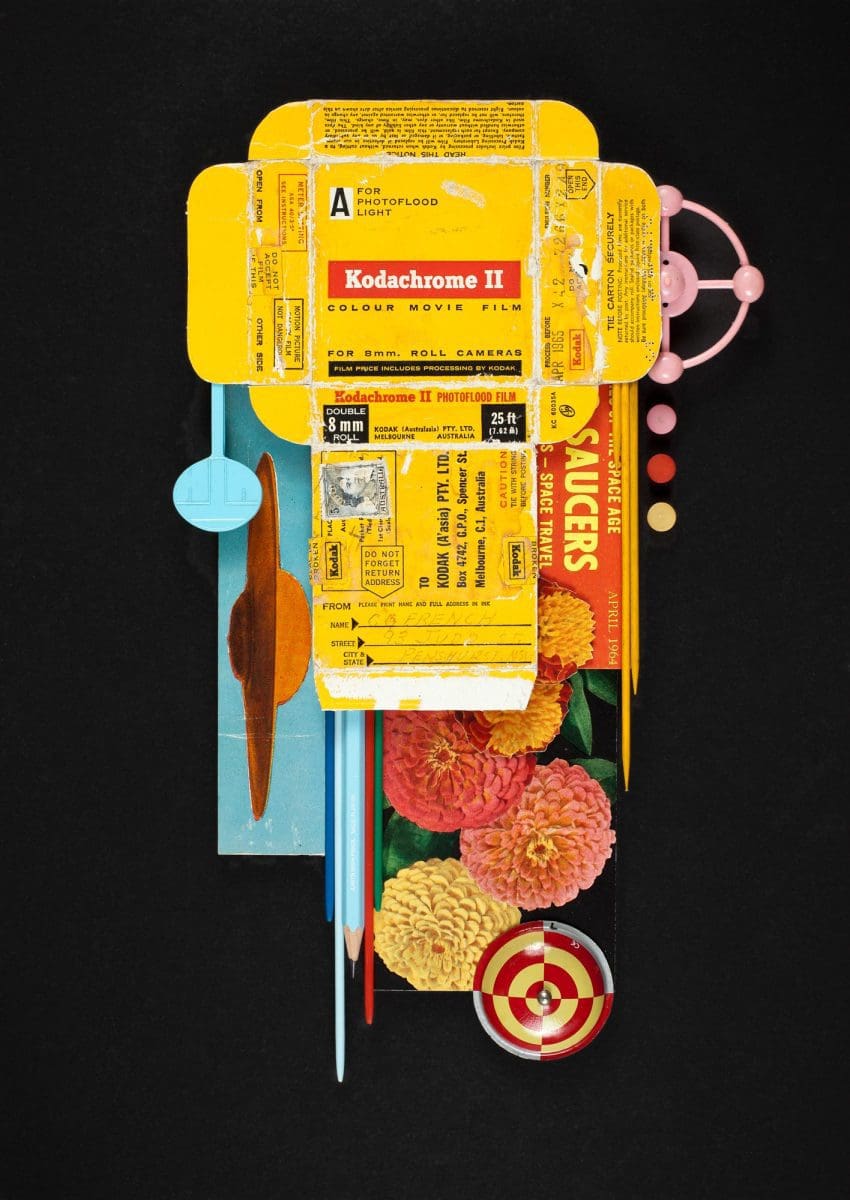

Powditch uses flowers throughout Codakhrome to suggest romance and youth, but also decay. These images, cut from botanical books from the 1950s, set the colour palette for each work. “That was a very conscious decision. I wanted each piece to have its own individual emotional feel,” he explains.

The flowers frame memory in terms of rich sensory experiences, but Powditch also uses elements that are a little flatter. The exhibition title is a misspelling of Kodachrome, a technicolour film that “recorded our entire history throughout the 20th century. It basically dominated,” he says. “I like the fact that it’s an obsolete technology that recorded everything.”

Powditch understands this impulse to transfer memories to photos and other objects. He has been a collector all his life. But not a hoarder, he says. He’s too “orderly and tidy” for that. He says an unsettled childhood might have had something to do with it. “It was a way to hold my life together, so I kept things. I’d move to a different bedroom and put the same posters up.”

But if memories can be held in objects they can also be manipulated. One series of smaller assemblages uses the famous red and yellow Kodak packaging. “They’re somebody else’s films and memories from the early 1960s,” he says. “I really liked the idea of taking somebody else’s boxes of memories and inserting mine into them.”

The emotional subject meant a new way of working for Powditch. Past exhibitions have dealt with more literal themes, such as politics, the environment and movies. “Normally, I would start a work, finish it in a week or two weeks, and move it off the bench, never to be touched again,” he says. Codakhrome demanded more time and patience. He worked on multiple pieces at a time and moved between them. “There was far more trial and error,” he says. “It also afforded me the time to go out and find other pieces.”

The works in Codakhrome use objects like coloured pencils, records, knitting needles and toys, but also film strips, sample cards, and landscapes taken from a ‘how to paint’ book. Pianola rolls, printed with back-to-front lyrics, suggest the passage of time. Another larger piece, Rosebud, 2019, incorporates pages from Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, a sci-fi story that asks whether memory makes us human. Powditch is clearly fascinated by similar questions. In Codakhrome, memory is fallible but so are the tools we use to record it.

These days, Powditch, like the rest of us, has a massive library of digital images. He shrugs. “It’s never looked at.”

Codakhrome

James Powditch

Arthouse Gallery

2 – 18 May