James Brett is the founder of The Museum of Everything, a collection of 2000 works by some 200 people who mostly don’t call themselves artists. Brett has a background in film, photography, architecture and design. Steve Dow met him at Mona (Museum of Old and New Art) to discuss the show and the line between insider and outsider art.

Steve Dow: The people in The Museum of Everything make art, not for us, but for themselves. Are you trying to break down the barrier between insider and outsider art?

James Brett: There is no such thing as outsider art. There are no outsiders. There is no such thing as disability; there is only ability. We create the distinctions, but art, as a concept, was also created by us, and it existed a long time before the word.

SD: Do academics then compartmentalise what you do?

JB: Oh yes, they always have, but that doesn’t hurt. If there were more academic studies of this field, it would be better understood. I’m here to show a platform of 200 artists, and wherever they’re from geographically, whatever their complicated life stories, each becomes representative of another 1000 artists all around the world.

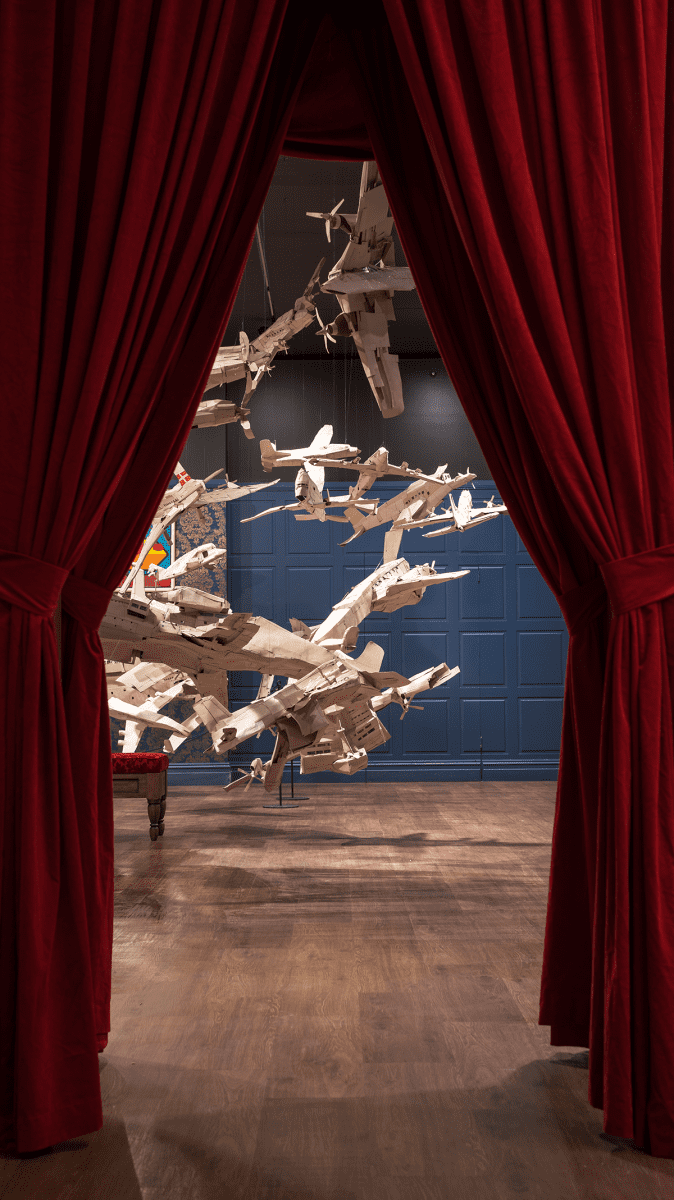

SD: The Museum of Everything started as a temporary exhibition in a former recording studio in London, in 2009. You’ve said that the 30 rooms at Mona are set up like a posh house gone to seed. How many places has it been seen?

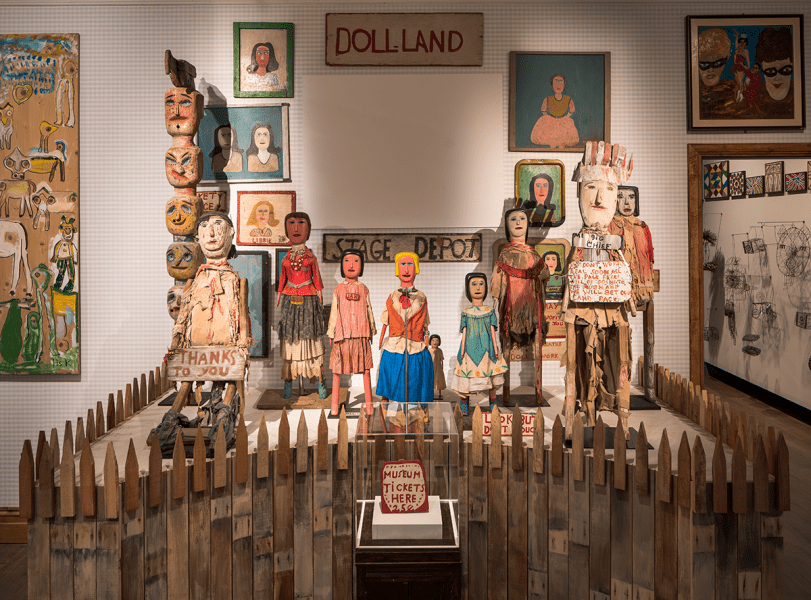

JB: I’ve lost count. We’ve done, like, a dozen exhibitions. The show at Mona is certainly the most coherent evolution. We’ve really tried to create something that tells a more specific narrative. I like the idea of created worlds.

SD: You and Mona founder David Walsh both have art collections based on individual idiosyncratic taste, so do you have a simpatico relationship?

JB: Absolutely. David sometimes looks at some of the work and cocks his head like a spaniel that’s not sure what’s coming for lunch, but at the same time, he’s been very embracing. We’re both humanists, and we’re both interested in bums on seats. Neither of us are interested in the sort of art bullshit of making the kind of show that five people see and 10 people understand the jargon on the walls. I’m not interested in jargon. I’m interested in language. Each artist has a language.

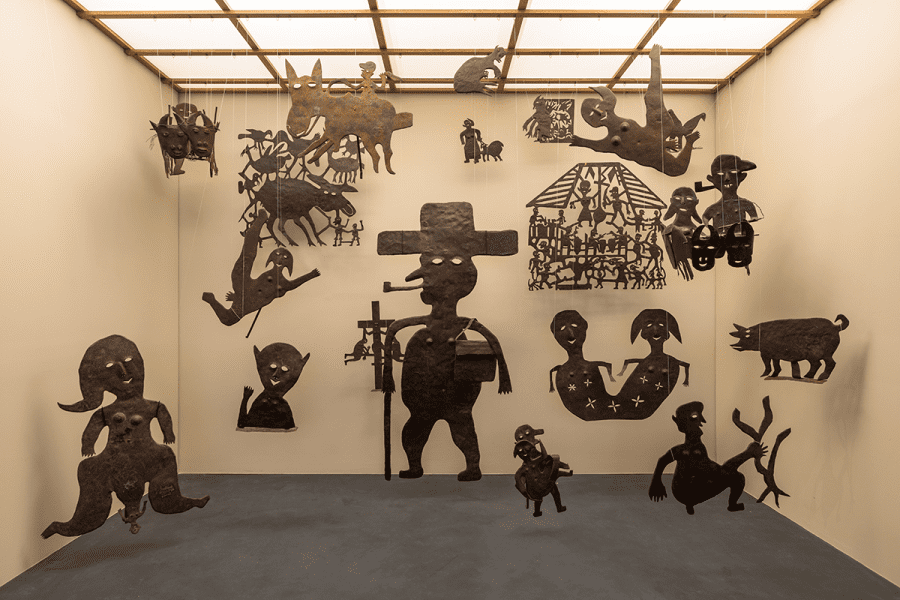

It’s like walking into an old museum that exists here in the middle of Mona. The contrast and conflict is huge. We start with notions of time and dimension, then move into the spirit world, to belief and identity, then lust, and desire and damnation, all inter-connected, and then youth, and the outer-cosmos and utopic architecture. It’s 30 exhibitions and the challenge is to make it cohere.

SD: There are dado walls, some with wallpaper, and chairs in most rooms. Whose house are we in?

JB: Well, first of all we’re in my old house, which was a terrace in Primrose Hill in London, in which I discovered I could actually hang things on the ceiling. That was my first experience of trying to arrange and organise material, which was a million different colours, and all conflicting.

I’m inspired by other museums. I also work closely with a movie set designer called Eve Stewart. My initial idea was to take over the whole of Mona, and then we all agreed that this was a little over-ambitious. It’s Adrian Spinks, the Mona designer’s fault. We had a month to put this together, and I said to Adrian, “How high are these ceilings?” And he said, “Three metres.” And I said, “That’s about the height of a posh house.” So that’s how we started. It was an ensemble effort.

SD: In room two, I had a smile on my face seeing Julia Krause-Harder’s five dinosaurs, one made of cassette tapes and cases. Is this saying, ‘In the beginning, there were dinosaurs?

JB: Absolutely. Julia’s dinosaurs were made in a studio for learning-disabled artists. Julia has a form of autism. She’s very verbal and can talk widely. I am completely in love with the dinosaur made up of small plastic dinosaurs. It’s an astonishing piece of postmodernism, but she doesn’t describe it as that at all. She says, “Well, these little dinosaurs are anatomically incorrect so I used them to make an anatomically correct dinosaur.”

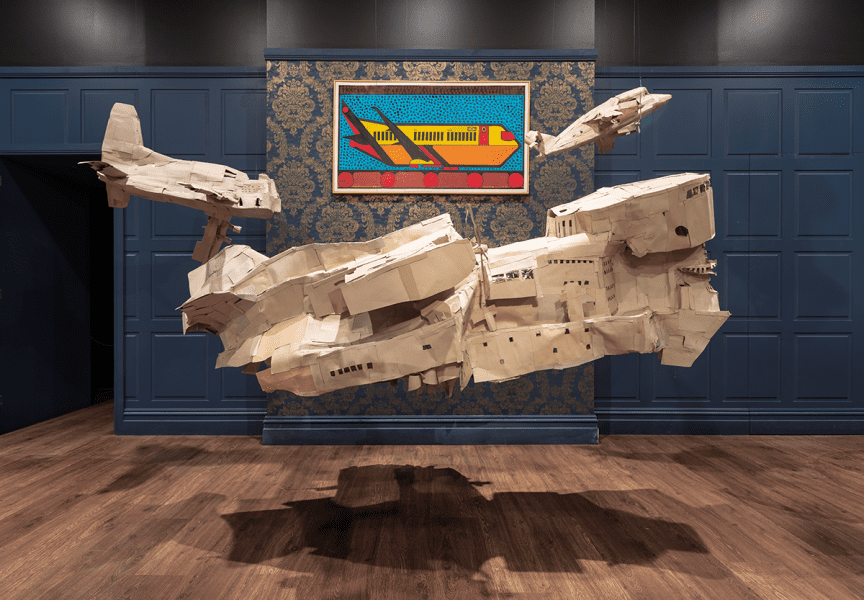

SD: I read André Robillard’s colourful 22 Firearms as ironic comment about art in the service of propaganda. There’s a toy Noddy atop the biggest gun.

JB: There is no Freudian interpretation allowed in The Museum of Everything. There is no symbolism here. People are not making ironic comments. People are making direct comments about their lives.

André Robillard is a delicate man who lives in a hospital. He started making rockets and spaceships. He came to our last show and I interviewed him. He’s an adult with a communication issue, but he’s bloody funny. I can show you a film of him speaking Martian.

SD: You have Augustin Lesage’s paintings. He was a healer guided by voices and there are gods and pharaohs and totems. He’s a former coal miner. Were you interested in what the artists had done before they became artists?

JB: Lesage was the best known of the French spiritualists. He claims to be channelling the spirits, but he’s also trying to convert you to Spiritism. It’s about conversion to a belief, as Malcolm X would say, by any means necessary.

I’m very interested in him being a miner that converted, and somebody who was guided. That work is in the room of agency, meaning loss of agency. Can you really admit you’re an artist? How does someone who works down in the mine say that?

SD: Is calling yourself an artist more difficult when you’re working class?

JB: That’s very true. Calling yourself an artist is difficult, period. Most of the artists in The Museum of Everything don’t dare to call themselves artists, or if they do, it comes after a long period of time.

We have an installation, by road engineer Nek Chand, an Indian artist I got to know who died last year, and he created this huge garden in Chandigarh. I said to him, “Are you an artist?” And he said, “Oh, no, no, I’m just working.” I said, “Well, why did you start doing this?” And he said, “God is in every stone.”

For him, the spiritual dimension is very connected, and the idea that you can make a kinetic work of art, it’s a theatrical work that 10,000 people visit a day, I guess I’ve learned a lot from Nek Chand. How do I make a place where lovers can come and hang out, or where people can play.

SD: The two painted doors by the US street preacher Reverend Anderson Johnson, who converted his home into a faith mission, struck me. I’m wondering how you would define your own spirituality?

JB: When I get exposed to that much of it, I can’t help but start to connect to it. I wouldn’t say I believe in any of the things that are on display, but I believe in the belief in them. Rather than embracing the sublime, my own transcendence is through the engagement with this material, and engagement with people who have had revelation. So my own revelation is through them.

The Museum of Everything

Mona

10 June – April 2