Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

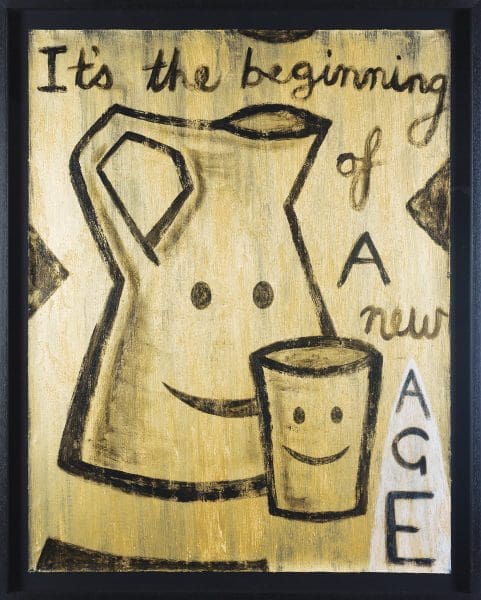

One of Nell’s paintings, delivered in black, gold and white, declares, “It’s the beginning of a new age.” Originally found in the Velvet Underground song New Age, the lyric comes at the tune’s finale, and it doesn’t quite know which way it’s heading: the knowledge of leaving an old life behind is held against the lamentation of time passing, which is overrun by the urgent promise, and slight trepidation, of the future. It’s the limbo in between these feelings that’s meaningful: it’s not unlike a moment we’re in now, and it’s not unlike a moment found in much of Nell’s art.

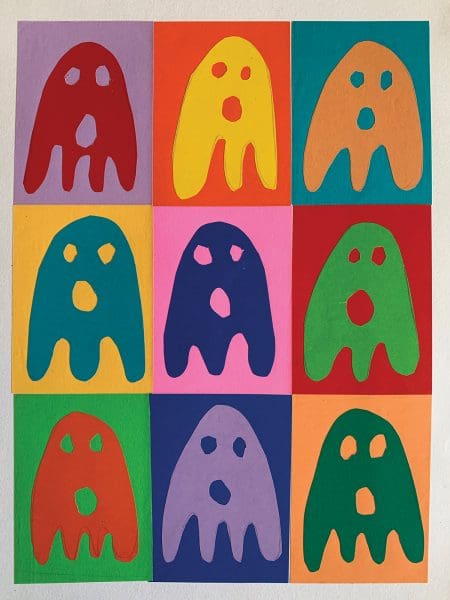

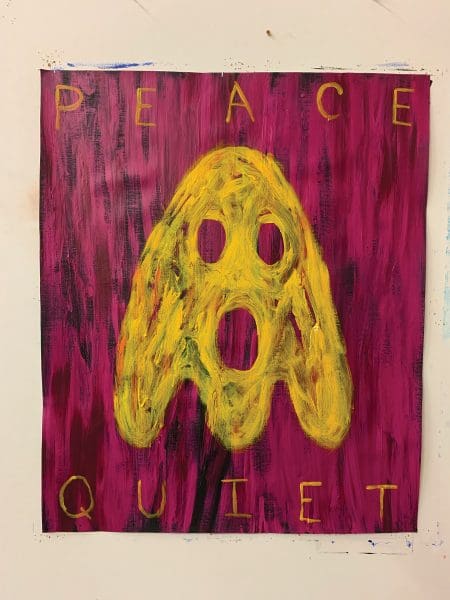

Alongside rock references, Nell has many signatures. She places smiley faces on objects like gravestones; she’s created an entire visual language with her painted and sculpted ghosts bearing “O” shaped mouths; she often uses lightning bolts; and she seamlessly weaves the pop with the spiritual. Yet in borrowing gestures from popular culture, Nell isn’t making an ironic comment, staking out a theoretical position, or pointing to pop’s commercial tendencies— rather, she shows its profundity. She takes an AC/DC lyric from its original world and gives it new meaning, while also honouring the context it came from. “I like celebrating,” agrees Nell. “I think there’s an element of my work that’s very child-like and simple, and I think in many ways I’m still that teenager in my bedroom listening to Triple J in wonder at a song.”

And just as a teenager may self-confine to their room, a global pandemic has placed us all in domestic quarters. Nell’s studios at Carriageworks closed in late March, her residency in Auckland was cancelled and her group exhibitions were postponed. Now she’s getting used to Zoom meetings and Zoom yoga, is working from friends’ studios or a Bunnings table at home, and establishing an online community quilting project. “I don’t think I’ve had a day off,” she says. But within this new routine, music and spirituality are still key figures.

Nell’s formative aesthetic experiences in childhood came from two places: rock’n’ roll and church. “Firstly, it was the radio,” she remembers. “I used to listen to Saturday Night Jukebox, and I used to sleep with the radio on and it was like ‘Splish, splash, I was taking a bath.’” She laughs, singing the song.

Her first transcendental experience was going to church—but even this moment, in its retelling, is linked to rock culture. “There wasn’t so much visual richness, should we say, in Maitland,” says Nell, describing her regional hometown five hours from Sydney. “I remember seeing boys walking down the street with AC/DC shirts and ripped hair and long jeans and it was like a whole look, but then church also had its whole aesthetic world, too. It was the stage, and crosses, and the architecture and the space. And it had music, so it was like my first-ever concert hall. We used to go to a Baptist church and people were baptised and it was quite a performance. It was like a religious experience, but more a whole aesthetic experience, a systematised experience.”

And like music, it was a repetitive experience that could be shared again and again. Soon, after attempting guitar but lacking a music community (and realising she “quite frankly just didn’t have any musical talent”), Nell began favouring painting.

Nell’s nascent spirituality would later find a home in Buddhism, which she was introduced to by her teacher-turned-mentor, artist Lindy Lee. Nell was Lee’s studio assistant and lived with Lee, helping with everything from dinner parties to packaging artworks. “And it was not only about being an artist,” adds Nell, “but being a human being.” Lee was practicing Buddhism and meditating daily, and a few years later, after the catalyst of a breakup, Nell began meditating too.

As the artist knows, the experience of meditating isn’t necessarily dissimilar from the experiences one finds in music and pop culture. These two facets are often described as “tensions” and “dialectics” in her practice, and to some extent they are, but they coalesce, too. “I think it’s a really natural synthesis,” agrees Nell. “I also found there’s so much gravitas and spiritual dimension to what seems like a throwaway line to a rock song or a pop song.”

The sense of holding multiple things, of intuitively understanding their connective logic, is also held in the personal. “When I was young I was torn between being attracted to men and women and was bisexual and feeling pulled both ways,” remembers the artist. “A lot of my work—like using the lightning bolts of AC/DC was a colloquial slang for bisexuality—that’s part of the reason I was using it. How can these different tensions be reconciled in one thing?”

Such tensions don’t necessarily have to reconcile, but nor are they opposing: pop and spirituality, joy and sadness, comedy and tragedy—they’re all held in ways that communicate an unconscious, underlying logic, often propelled by a particularly Australian mode of humour, the kind found in films such as Muriel’s Wedding and The Castle, generally as sincere as they are despairing and parodic. “Sometimes you can amplify the tensions, and sometimes you can reconcile them,” explains Nell. “But, really, you realise language has let you down a bit in those binary terms and there’s a lot in between that doesn’t have a word.”

Within this gap lies the possibility, even the necessity, of communicating in a common aesthetic language, to say, as Nell puts it, “bigger things about life and death.” Like what? “Like, what about our mortality? And what kind of sexual beings are we? Who are we? What happens to us when we die? How can you reinstate urgency into your life because you know you are going to die? It’s like the painting It’s the beginning of A new AGE. That’s every morning.”

Nell’s Mini-monograph, aptly titled Nell, is being published 28 July 2020 by Thames and Hudson.

Nell is represented by STATION Gallery, Melbourne.