Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In 2019 Kaldor Public Art Projects celebrates 50 years of creating art projects working with artists in public spaces. To commemorate this milestone, Art Guide Australia is bringing you a series of articles talking to the people behind the projects, exhibitions and events.

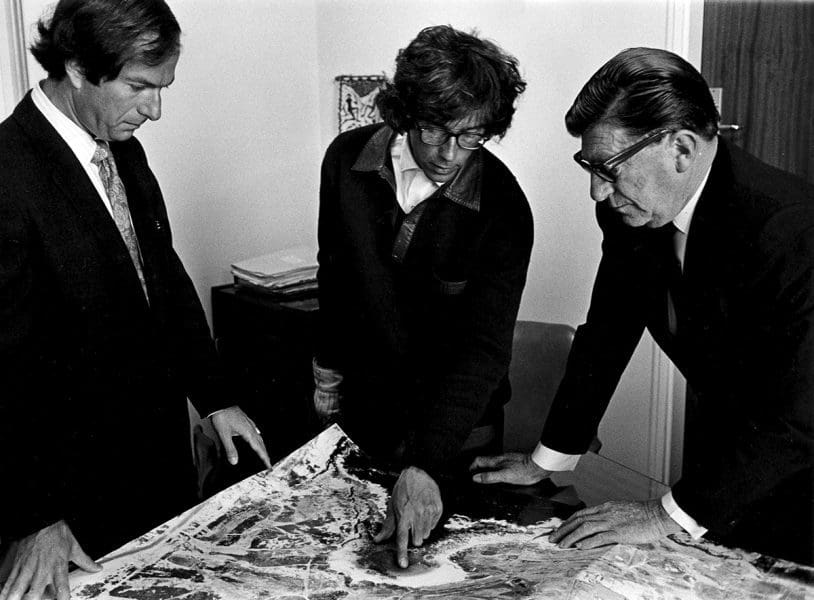

It All Started With a Stale Sandwich is a documentary about the 50-year history of Kaldor Public Art Projects, made by London-born, Sydney-based film director Samantha Lang. The title refers to the humble lunch Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and artist partner and wife Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon offered Kaldor during their first impromptu meeting in the couple’s low-rent, rundown New York studio in 1968.

In 1969 Wrapped Coast, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s sensational two-month show, became the first of Hungarian-born Australian textile king John Kaldor’s art events in Sydney. Lang’s challenge was to tell the story of 34 public art projects and their impact over half a century. Not all of the 50 on-camera interviews have made the final film. A first 80-hour-long cut of the documentary has been reduced to 94 minutes for its premiere at the Sydney Film Festival, and it will also get a limited national release in cinemas. A 60-minute version will be cut to air on the ABC, with a few possible additional mini-films for broadcast.

Lang says there is “a little” of Kaldor’s life story in the documentary, even though he requested when being interviewed that the film be about the artists. Lang has artistic freedom, her film being funded by Screen Australia, the ABC and Create NSW, and not by any Kaldor-related sources.

“John Kaldor already has an incredible website with all of the projects,” says Lang. “His narrative is very well curated by himself, and I didn’t want to make a hagiography. I did want to talk about the art and the impact it has on the cultural landscape, trying to find a balance of John’s personal story vis-à-vis those other things, and not fall into an Australian Story-type narrative – but at the same time, John is the glue that holds this story together.”

Kaldor’s parents fled the communists in 1948, eight years before the Budapest uprising, and the family spent much of 1949 stateless in Paris, when John was 12. He cut a deal with his mother that he needn’t attend school there provided he studied in museums and galleries, and so each day, getting by on pidgin French and visiting the Louvre, the Museum of Modern Art and the Rodin museum, as well as taking side trips to Versailles and Fountainbleau, Kaldor gained a thorough knowledge of art.

The first country to offer Kaldor’s family resettlement was Australia, which in the 1950s was a remote place both in distance and culture, but Kaldor would prove to be a cultural maverick. “John’s whole notion of public art projects is that it’s something that should be gifted to the public at no charge,” says Lang. “They don’t have to think of it as art, but it should be a disruption in their daily lives, to the landscape and to the culture.”

Kaldor met his third wife, the Melbourne-based businesswoman and fellow arts philanthropist Naomi Milgrom, in 1995, during the time Kaldor brought the giant floral Puppy, by US artist Jeff Koons, to Australia, placing it outside the Museum of Contemporary Art at Sydney’s Circular Quay. Lang says Puppy is “fascinating” as a work, and her documentary includes an interview with the engineer responsible for helping the artwork stand up when it had previously fallen over in an attempt to erect it in Germany.

While making the film Lang was told stories of difficulties working around artists. Lang says she left out of the documentary one tale surrounding Swiss-born artist Urs Fischer’s installation at Cockatoo Island in 2007, in the days before the former prison island was opened as a camping ground and regular Sydney Biennale venue. “There were countless water taxis sent out for a glue stick or a ruler or whatever,” says Lang. “Fischer wanted to put a cast-iron wardrobe into one of the sites … but he didn’t measure it properly and it didn’t fit through the door… One of John’s great qualities is his patience, so he said, ‘What’s it going to take?’ So they had to ferry a crane out to get the wardrobe into the site. There are surreal images of this cast-iron wardrobe being craned through the air.”

One of Lang’s favourite experiences in making the documentary was interviewing Gilbert & George in their London home. Gilbert, born in the Dolomites in Italy, and George, born in Devon, England, were feted by Kaldor in 1973, striking besuited poses on a plinth for five hours a day for six days at the Art Gallery of NSW, then repeating the exercise at the National Gallery of Victoria, singing along to a cassette of the 1930s British song Underneath the Arches as they passed a cane and gloves back and forth.

Their life as performance art is not a rehearsed act, she found. “They do things in time with each other without cueing each other,” says Lang. “It’s very uncanny because you don’t see any signalling between them, but it’s always perfectly in rhythm.”

Notable female artists Kaldor brought to Australia include performance artists Charlotte Moorman (with Nam June Paik) in 1976, Vanessa Beecroft in 1999 and Marina Abramovic in 2015. But what of the lack of female equity? Lang shakes her head and smiles. “Obviously that was something that came up, and I asked John about it too. But what I found – which is not an apology, but it was curious – is in fact the impact of John’s projects means a whole diverse range of artists and audiences connect with the artists John puts on.”

The first project by an Aboriginal Australian was Jonathan Jones’s barrangal dyara (skin and bones) at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens in 2016. “What’s remarkable about John is he hasn’t stayed in the Western canon,” says Lang. “He’s chosen to move with what’s contemporary.”

Naturally Lang’s documentary, It All Started With a Stale Sandwich, spends some time focussing on the project that really started it all, Wrapped Coast. The crowds came to mock but they stayed to marvel, grappling with seeing their landscape anew. Lang discovered not everyone was enrapt; some Australians vilified the project, questioning its relationship to art.

Two nurses then employed at Prince Henry Hospital near the Little Bay cliffs revealed to Lang that, after volunteers spent the day tying down the fabric on the cliff face, the nurses would cut the ropes at night because they found the artwork strange.

“The nurses had to work 12-hour shifts and had to be back in their accommodation by 10pm,” Lang explains. “So they had this rigid regime, and they thought perhaps this was a way of them having some power or control, and also their getaway was going down to the beach, and they hated this work taking over, so they would go and cut the ropes at night.” The full explanation for this vandalism – which was news to Kaldor – doesn’t make the film.

Jeanne-Claude passed away in 2009, but Christo was robust and nonchalant when Lang told him of the rope cutting during their interview for the documentary. “There are many ways people are interpreting this work, even the most negative,” replied the artist, who turned 84 in June 2019, a year older than Kaldor. “What can you do about that?”

Still working and planning to wrap the Arc de Triomphe in Paris in silvery fabric and red rope in 2020, the Bulgarian artist told Lang that the wrapping references his youth when he and fellow art students would be sent to summer camps, assigned to cover up dilapidated farm machinery on farms so that Westerners passing by on the Orient Express would not see the run-down state of the equipment. “Really, the wrapping is about what you can and you can’t see,” says Lang.

Today, Christo is still stateless, having emerged out of communist Bulgaria. He told Lang that he and Jeanne-Claude, who met in Paris in 1958, “used the capitalist system to be Marxist,” buying up their own past art to fund their public art and thus, from the time of their success with Kaldor in Sydney in 1969 onward, their vision was not beholden to others. “John bringing Christo here to make that work changed the cultural landscape,” says Lang.

It All Started with a Stale Sandwich premieres at the Sydney Film Festival on 15 June and will be released in selected cinemas in July. An hour-long version of the film will be aired on ABC in late September.

Art Guide Australia is proud to be a media partner celebrating 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects.