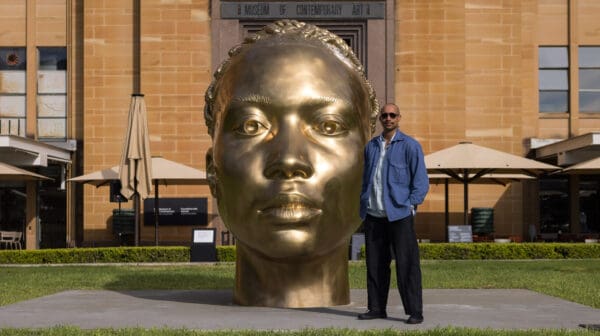

Australian Muslim Artists is an annual exhibition held at the Islamic Museum of Australia in Melbourne. Its aim is to showcase the diversity of the contemporary Muslim experience in Australia, and in the current political and media climate, that is something that should be celebrated.

There is no overarching theme binding this year’s exhibition. The common thread running through the show is the fact that the 20 artists identify as Muslim. These artists work in varying visual languages and techniques, from painting to sculpture, textiles and more. Some are new or recent migrants to Australia, others were born here, and many choose to express their identity through their practice.

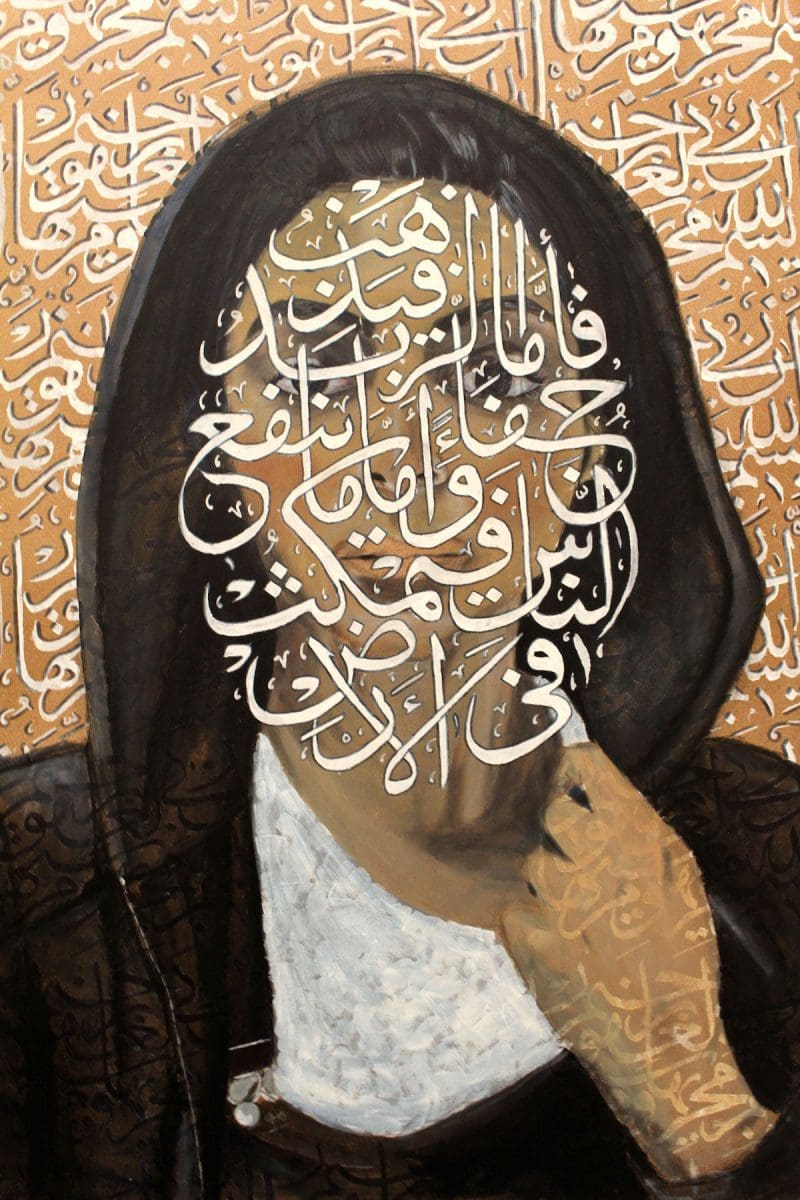

A number of the works by recent migrants are declarations of love for their new home, often with explicit use of Australiana symbols. For example, there are cockatoos in Lebanese-born Jamal Chahal’s painting, Cockatoo Love, 1992, and Samia Khan’s copper leaf on canvas map, Australia 1, 2018, is overlaid with Arabic calligraphy spelling out the name of her new country.

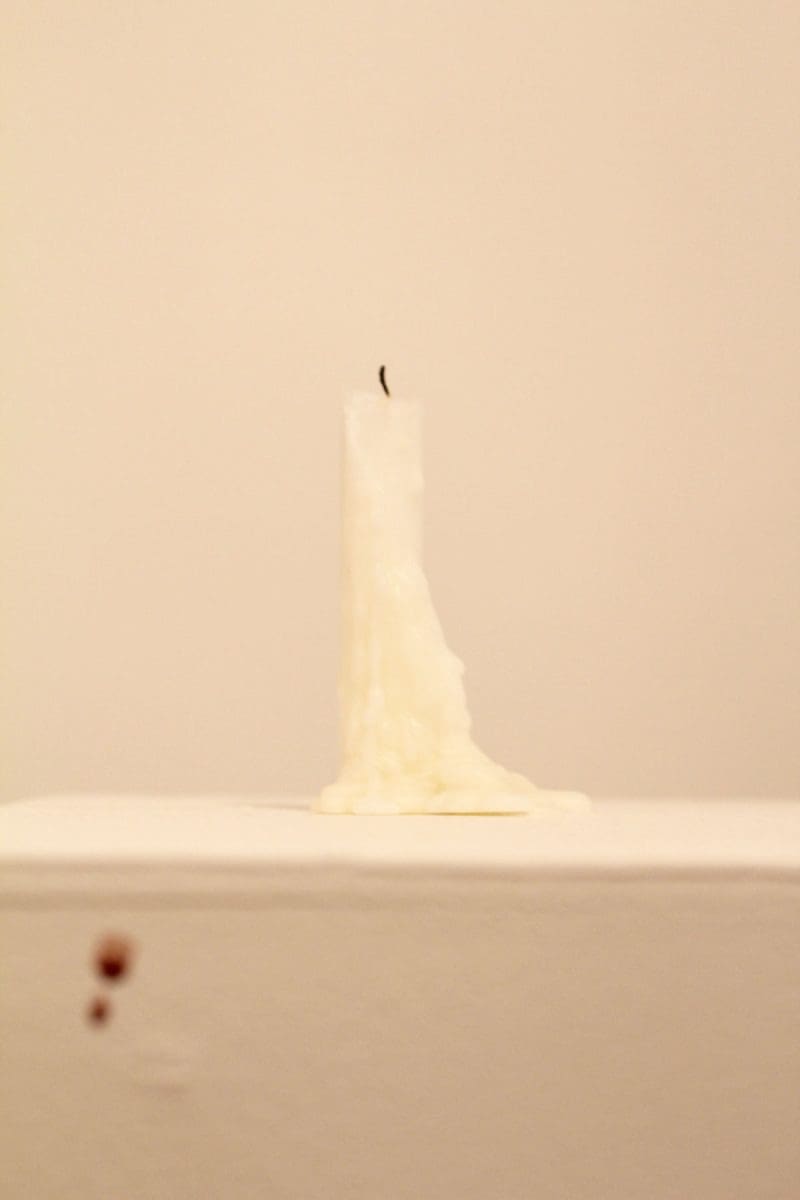

Given ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, it is not surprising to see works that explore the ravages of war and the refugee crisis. Iranian-Australian artist Mohsen Meysami’s four works in the exhibition all centre on these two interconnected topics. Most explicit is Happy Death-Birthday DEAR REDACTED, 2018, in which a lone wax candle sits on a plinth with a dried droplet of blood. It was inspired by a report in The Nauru Files, published by The Guardian in 2016, in which a child was recorded as saying to a caseworker, “I want to die on my birthday, it is not worth living here anymore.”

But it’s not all completely grim in Australian Muslim Artists. Textile artist Soraya Abidin’s exploration of spirituality, Welcome to Paradise, 2017, is a moment of white embroidered calm. Her vision of paradise is stitched into white silk, using materials and techniques learned from both her Malay and Australian ancestors.

Textiles, significant in early Islamic art, appear to be just as important today. Their practicality (as garments, carpets, weavings and more) and portability has probably contributed to their continued significance. Every Muslim culture, from Persia to Southeast Asia and beyond, has its own approach to materials and techniques.

Carpets and rugs are particularly significant in Islamic culture, crossing all territorial and cultural boundaries. Used for prayer and decoration, they are symbols of comfort and piousness. The destroyed Persian kilim rug in Mohsen Meysami and Mehdi Meysami’s collaborative installation, Woven into the Warp and Weft of our Land; Blood Blood Blood, 2017, proves the significance of carpets and tapestry in Islamic – specifically Persian in this case – culture. Here, a shredded rug hangs on the wall, leaving a threadbare window in its centre and a pile of threads on the ground: another reminder of war and violence.

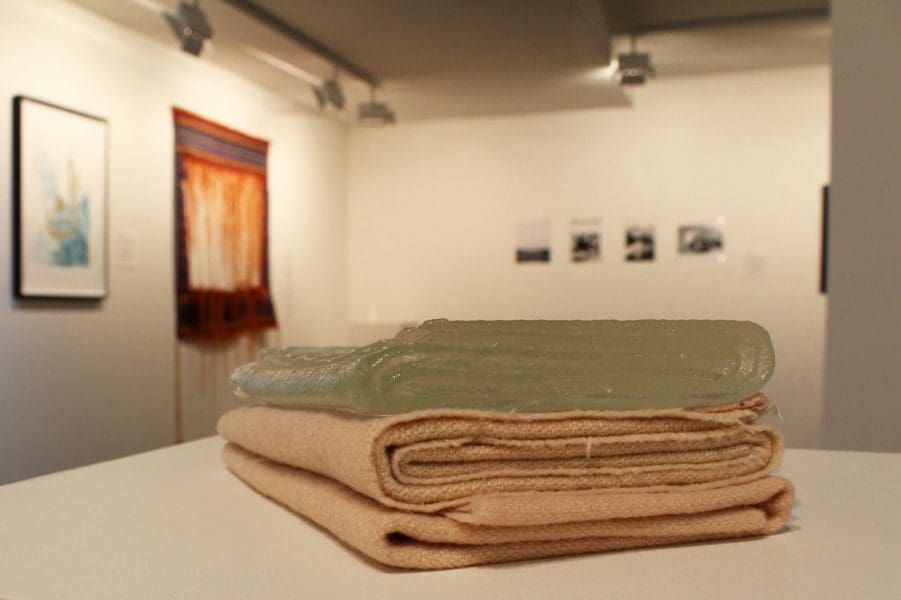

Racquel Austin-Abdullah’s installation You Left Something Behind (Wangkumara Woman), 2014, also uses textiles to share a perspective that doesn’t receive as much attention in the general scheme of the Australian Muslim experience: that of the Aboriginal Muslim. The history of Islam in Australia actually predates European settlement, with trade between Aboriginal fishermen and Muslim Southeast Asian fishermen going back to the early 1700s. In her work, Austin-Abdullah has reconfigured textile into glass to imagine her great great grandmother’s life as an Aboriginal Muslim woman.

Collectively, these individual voices are a reminder of the multitudes in Muslim identity and art. There is no singular ‘type’ of Muslim or Muslim experience, regardless of what we see on television or hear about in the news.

Australian Muslim Artists 2018

Islamic Museum of Australia

16 August – 15 October