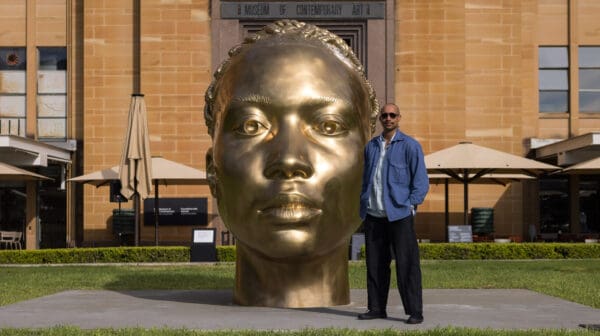

As artistic director of NIRIN, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, artist Brook Andrew is bringing together over 90 artists, creatives, collectives and communities from Australia and across the globe.

Tiarney Miekus: The Wiradjuri word NIRIN is the title of the 22nd Biennale of Sydney. Can you talk about the meaning of NIRIN and how it emerged as a frame for the Biennale?

Brook Andrew: I think firstly we needed a name that was not English, and because I’m Wiradjuri I think it makes sense for that word to be in Wiradjuri. While NIRIN translates to ‘edge’ in English, when you’re doing translations there’s always different understandings of a word. I think the interesting thing about nirin, and how it talks to the edge, is that it can also be the edge of a silhouette, or the edge of a carving, in a culturally specific and active way. Translations take us in many directions depending on perspective and circumstance, and within these different understandings of nirin, suddenly there are many edges and a playfulness, but most importantly it challenges what is the centre and what is the edge. While it’s a particular Wiradjuri word, in its reception, nirin takes on an endless number of meanings around and to do with the edge, all interconnected, and in this way the word is both a concept and a methodology, and conceptually a call to action of how we can see and be different instead of being separated and distant. There are seven themes underpinning this Biennale, each from Wiradjuri language and behaving in the same way. Wiradjuri language is extremely complex as it connects to ceremony, season and ways of being that are not linear as in most Latin languages. I think it’s reflecting on this complexity that assists with understanding what this Biennale is about.

TM: Unpacking that complexity, can you explain the idea of the ‘edge’ and how it relates to what is typically viewed as the centre in contemporary art?

BA: We often talk about the centre. We think we know the context of the centre in regard to the art world, but also generally within culture by referring to cities such as Paris, Dubai, Beijing or New York—but what is the centre? And what is the outside? We can become accustomed to the dominant historical legacies of cultures that see themselves as more progressive or first world in some cases, and we forget about a lot of cultures that are seen as being on the edge or not the centre, and we forget that they have ancient cultures and ancient roots, as well as new and vibrant trailblazing cultures. Like the Haitians, for example. They were the first country to free themselves from slavery and they are the trailblazers of this incredibly important change within history and slavery, yet they suffer natural disasters such as the recent commemoration of the devastating earthquake and have leading arts movements such as Atis Rezistans—though they are not seen as a centre. It’s points like these that I think need to be highlighted around creative practice internationally, where it doesn’t come from a historically, military or financially powerful centre.

I think stories from the so-called edge bring in a very different world view that’s often left out of the dominant art world, or even creative world.

Of course, people will say that artists from other centres from around the world, such as Haiti or remote parts of Australia, have shown internationally, but it’s not en masse.

TM: It seems that one of your foremost decisions in curating the Biennale is to ensure it is First Nations and artist led. Can you explain why this is not only important to you, but also important in a larger cultural sense?

BA: When we say First Nations led, I would argue it’s the philosophy of a First Nations methodology. There are many artists in the Biennale who are not First Nations and I think it’s important to clarify that because the methodologies around a Wiradjuri concept of how we see life and creativity is outside of the contained, often restricted, view of what art is. Under this, we can include [in the Biennale] people who are chefs or scientists, and people who work closely with communities or creatives to make their creative endeavours. For example, there’s Gina Athena Ulysse, who’s a Haitian anthropologist and spoken word performer, who—for the first time— is being shown in an international exhibition like this, and for her it was really exciting because she doesn’t come from your traditional art background. And then you have other artists like Laure Prouvost from France or Jose Dávila from Mexico who are not First Nations, but the tensions and imaginations in their work are very much aligned to the themes that I’m interested in and support those Wiradjuri methodologies.

TM: You’re the first Indigenous Australian to hold the position of artistic director of the Biennale, as well as being an artist in your own right, and currently pursuing a PhD at Oxford University. Every director will bring their own experience to the Biennale, but how do your experiences influence how you approached directing?

BA: For me, I think there is a very big international awareness in regard to what a biennale is, and in regard to how I see the art world, and I hope to bring a broader view that encapsulates different historical legacies. If anything, it’s made me aware: to beware! I think that things need to shift dramatically and urgently around the way in which cultures have been hijacked to display a particular kind of side or view. What I mean by that is there’s certain tropes in the art world and in the general dominant culture that need challenging. For example, biennales historically come from exhibitions which were based on colonialism and showing the wealth of those colonies, and that’s historically problematic for a lot of people because now, today, it involves considering things like restitution, which is a big issue at the moment. You even have Emmanuel Macron, president of France, bringing it to the forefront. Then there’s the repatriation of Aboriginal human remains. There’s one artist, Katarina Matiasek—she’s an Austrian artist in the Biennale, and her work will be demonstrating the links between Austria and Australia in repatriating Aboriginal human remains, and she’s been very much involved in working with Aboriginal communities.

TM: Would you say your curatorial ambition for the Biennale aligns with your continuous curiosity for stories that are left in the dark?

BA: Yes, and I think that there’s a lot of fear out there in allowing these other stories to shape the future. I think it is challenging for dominant cultures to understand or to let in people from other parts of the world to re-present their narratives and histories, because often it’s the dominant culture that has shaped people’s lives. I think it’s really important to trust other views, and to explore other views in a way that is going to help build a different kind of future. And this includes the urgency around the environment.

There’s devastation in Australia at the moment because of the bushfires, but it’s also a world topic of global proportions where the current dominant narratives and legacies need to shift. If there’s a brave approach to that [in the Biennale], I think it’s going to very rewarding.

TM: We’re currently speaking two months out from the 22nd Biennale and Australia is in the midst of a devastating bushfire crisis. Has this affected the Biennale and the artists involved?

BA: I think that the bushfires are something that happen in Australia yearly and while it’s very much part of the cycle of our environment and society, nothing like this has ever happened before. If anything, it really underlines the urgency of climate change and goes beyond First Nations management of land. This disaster also gives agency to artists like Adrift Lab who are world-class scientists working with creatives to really put a spotlight on ocean plastics and the devastation that’s already happening in islands off-shore. I think it also connects to the Brazilian artists in the Biennale who are mainly Indigenous and dealing with these issues—and we are all dealing with these issues, whether in Indigenous and other communities, but city centres often don’t experience that, or don’t really have an understanding unless we have a connection to outside the city centre. I think the Biennale is an opportunity to look at our environment in a holistic way to really see the effects of what’s happening globally. In saying that, two artists in the Biennale, Bhenji Ra from Australia and Jota Mombaça, a Brazilian artist, will be doing a collaborative piece reflecting on the recent bushfires, and the Tennant Creek Brio collective also reflect on traditional burning practices in their work. So yes, people are really alert to it.

TM: From the way you discuss curating the Biennale, I have the sense that for you it’s as much a moral endeavour as an artistic one?

BA: Well, I think it’s interesting when you first asked me about being the first Indigenous director and so forth—these are really important things to think about, but I could be one of a hundred Indigenous people and we could have got together a whole group of people to curate this, but I’ve been working very closely with communities and Indigenous and other curators internationally and locally, and putting our heads together and thinking about different people. And this is moral.

I think this is where we return to what is a Wiradjuri methodology or a First Nations methodology? It’s not just confined to particular tropes or ideas or aesthetic endeavours within a particular art sensibility.

It’s so much wider. It involves food and sharing and solidarity, and working together, and the earth— and that’s not a romantic view. It’s just the reality of how I think and believe that we work together.

TM: On the one hand, it seems as if you’re trying to capture a sense of fluidity and flux of hidden narratives, rather than reinforcing historically dominant narratives. You can most evidently see this through the inclusion of many First Nations, grass-roots, female, and gender non-binary artists. But when you’re wanting to demonstrate our times and art as one of flux, and you’re also having to curate a holistic event, do you find this to be a juggle?

BA: For me it’s not a juggle at all! It’s very natural. Really, it’s not a juggle for a lot people, except it’s not part of the way in which museums—and I say museums in inverted commas—traditionally have been architecturally or philosophically built. If we ask ourselves, “Well, what is a museum?”, the traditional museum is still very much part of that dominant European idea of what art is. It’s full of white walls, and paintings go on those white walls. The way in which we push against that is to allow the artists in the Biennale to have freedom of expression to see how they can work within those spaces, and that’s always going to be tough when you’re working on a white wall because for many artists that’s not a natural condition.

Very few artists in this Biennale have said, “Brook, I want a white room.” There’s only one artist that’s requested one.

TM: In the language surrounding the Biennale there is the position that art can incite change, whether that’s change through action or consciousness. The ability for art to do this—how much has it been on your mind when curating?

BA: I think that artists do this naturally anyway!

TM: But maybe it’s not always natural for curators.

BA: I can’t really comment on that because I’m an artist. I’m not a curator. My role, in inverted commas, is artistic director. I see myself as someone who can help artists shine or help artists express themselves. My job is there to give them a platform. I think that within the art world, and with the public, biennales are often under the magnifying glass and I think I’m there to ensure artists have the freedom to talk about urgent or personal issues and changes that they feel is the zeitgeist.

TM: It seems as if you’re aiming to cultivate a great poeticism to the Biennale and imbue the event with a kind of optimism, drawing upon the sense in which art has the power to heal and transform. Can you explain this further?

BA: I think art has many tropes, meanings and feelings, and sometimes these are confrontational, but I think in this case it can also be a breath. Like taking a big deep breath and connecting things or ideas or aesthetics or feelings that are often not connected under big dominant narratives around cultures. It’s an opportunity for us to think or feel differently about something, and it’s those kinds of chances, or deliberately juxtaposed ideas or feelings, that can be invigorating. I think that’s what we need right now. We need a kind of invigoration that’s empowering. Maybe it’s to make new friends, or to re-look at something in a different light, or to let go of something that’s been eating at us, or to join hands in a different way. And I’m not being wishy-washy about this. I mean it in a very pragmatic way.

NIRIN

22nd Biennale of Sydney

14 March—September

(closing dates vary, check each venue)

This interview was originally published in the March/April 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.