Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

They were giants of the New York art scene of the 1980s, stratospherically popular with collectors and the public but snubbed by art institutions during their short lifetimes. Keith Haring, born into a church-going white family from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, of Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage from Brooklyn, were friends who ran in converging art circles with Andy Warhol at its epicentre. A healthy rivalry marked Haring and Basquiat’s mutual respect, contends the curator of a premiere exhibition that brings their work together.

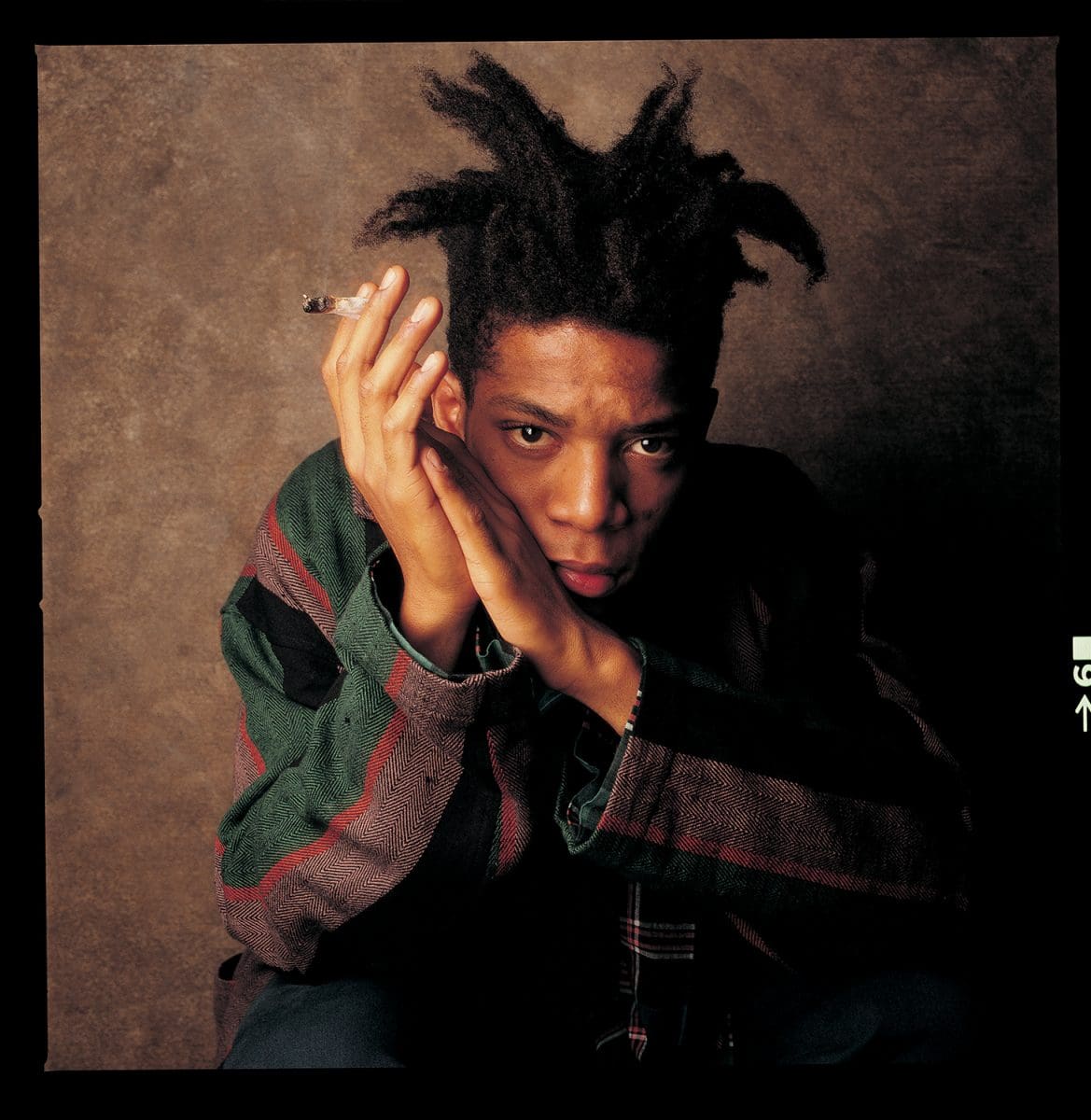

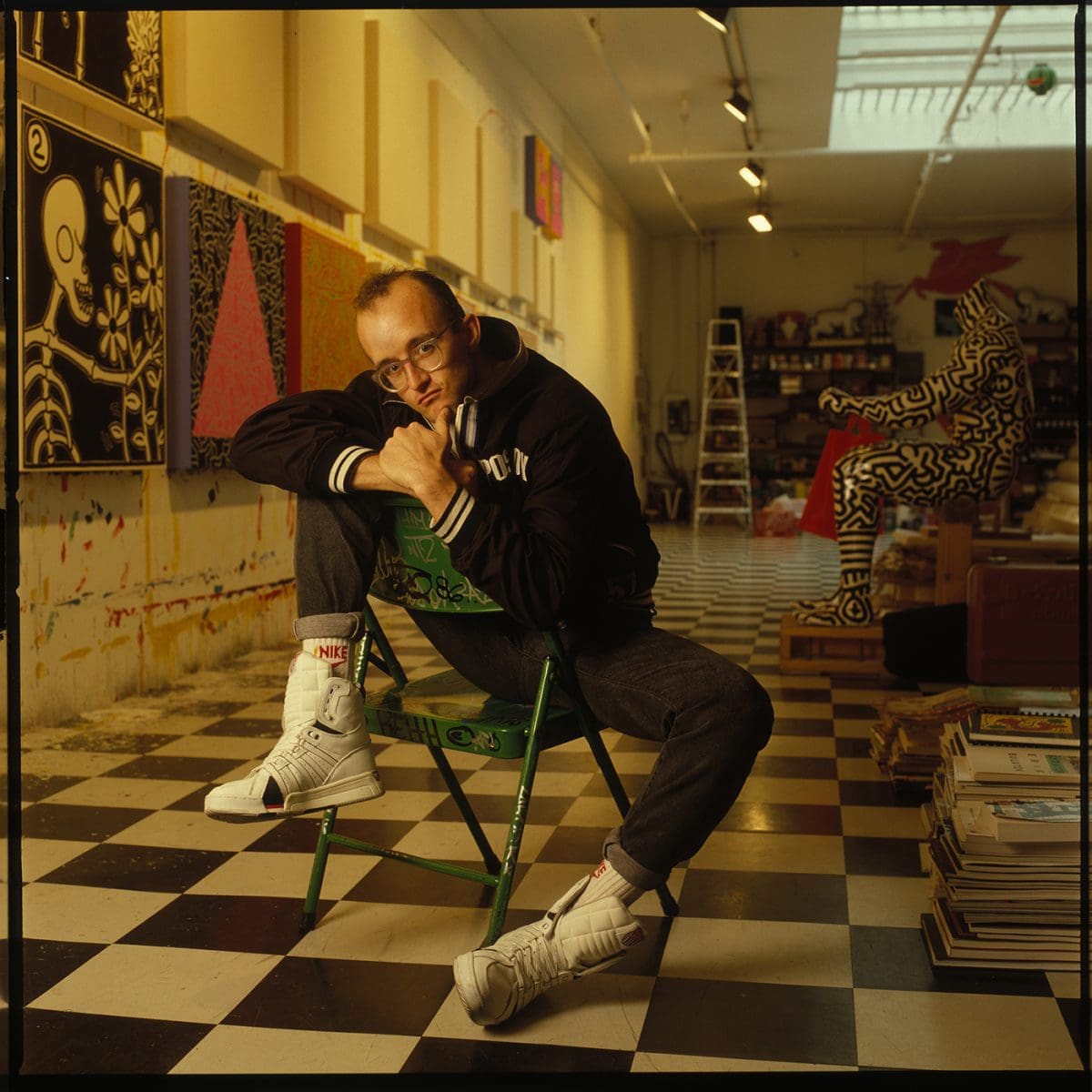

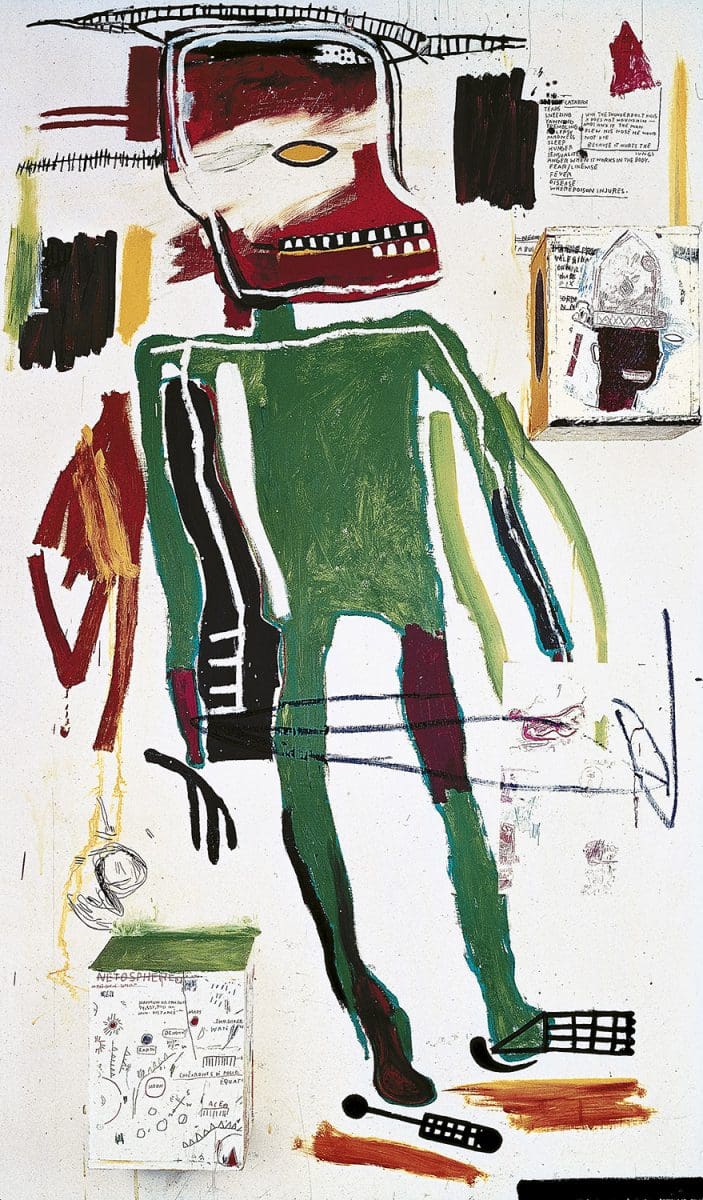

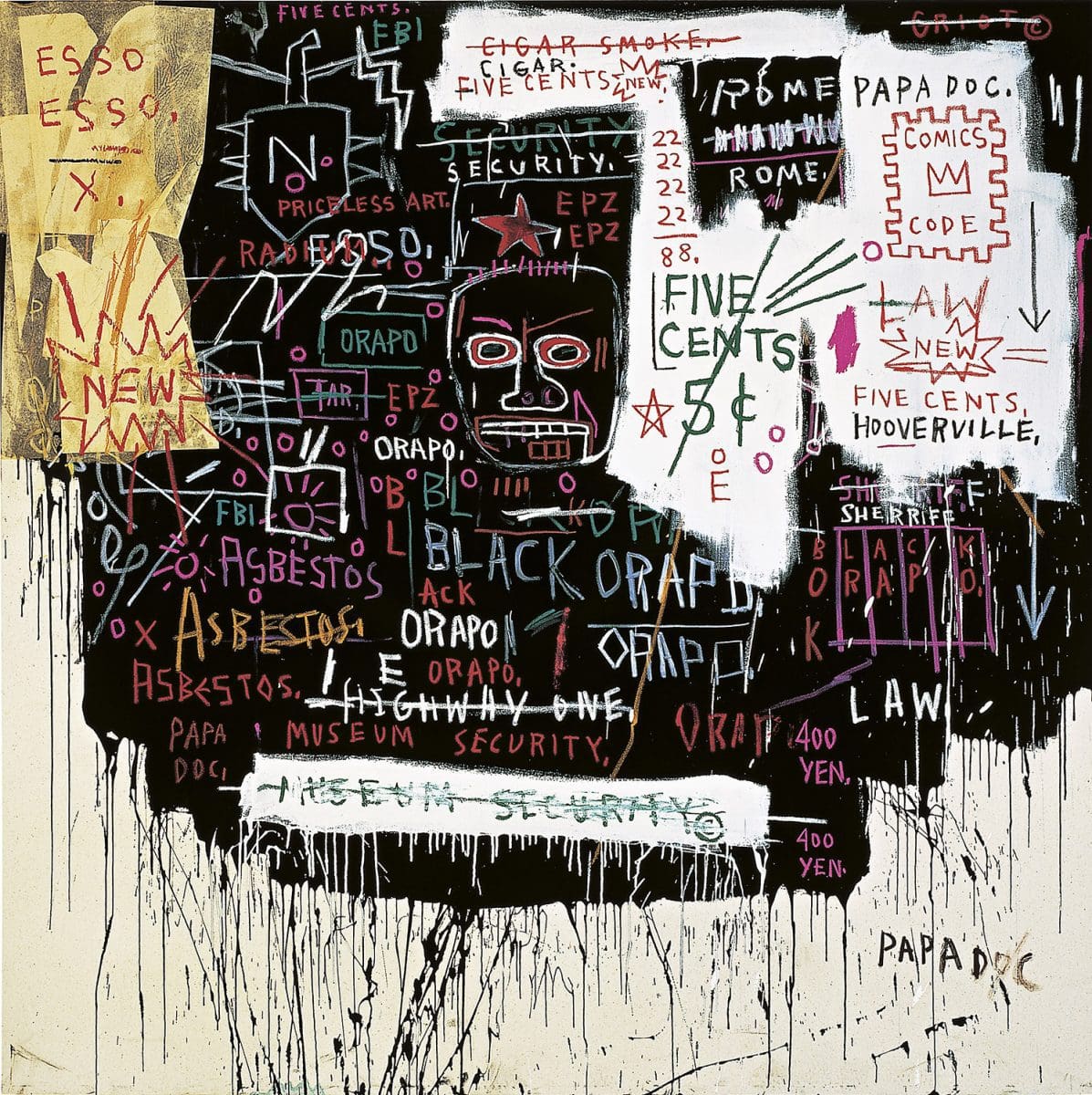

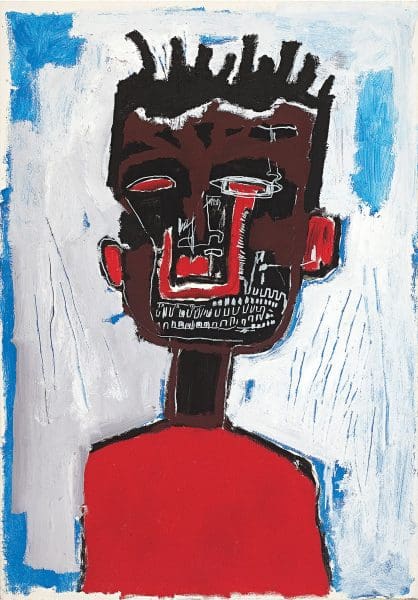

Keith Haring deployed his distinct thick, curved line in thousands of impromptu subway chalk drawings of dancing human and animal figures – his street art once saw him arrested for ‘criminal mischief’. He flew across the world to paint huge community murals – including at Collingwood Technical School and the National Gallery of Victoria’s water- wall entrance – and made a crawling baby his hopeful symbol of humanism. Meanwhile, Basquiat sought the certainty of galleries, graduating from spraying poetry outdoors in SoHo under the pseudonym SAMO – short for ‘Same Old Shit’ – and painting on salvaged doors. He created elaborate canvases of bold, often dark subject matter that 30 years after his death command higher prices than any other American artist.

When Basquiat died of a heroin overdose at 27 in 1988, Haring’s personal journal ran silent; he was instead writing a moving tribute for Vogue magazine. Basquiat was “the supreme poet: every gesture symbolic, every action an event,” wrote Haring. “He used words like paint. He cut them, combined them, erased them and rebuilt them.” William S. Burroughs’ practice of cutting up texts influenced both Basquiat’s and Haring’s thinking and early work, although Haring had also studied semiotics: the theory of signs that sees images function like words.

Experimentation was key: Basquiat, with his painting technique of scratching out and erasing would “create with whatever materials were readily available on whatever surface would sit long enough to draw on”, noted Haring – who was himself “repulsed” by canvas and oils, preferring watered-down ink and cheap paper or muslin and acrylics. Haring painted in different directions, playing with both three-foot long and double brushes.

“Both artists were about the line,” says Dieter Buchhart, curator of Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines at the National Gallery of Victoria. Speaking from Vienna via Skype, Buchhart says “Haring created a forerunner of our emoji culture: an image language, and he used these symbols in different combinations. The difference with the emoji culture today is that Haring’s symbols had multiple meanings. The idea of an image language dates to the [ancient] Egyptians, whose writings influenced Haring.

“With Basquiat, his paintings and drawings, everything was about the line, even though it looks much more painterly. It’s an existential line, defining the human existence and human existential fears.”

Both artists shared a sense of social justice: Basquiat was deeply affected when African-American graffiti artist Michael Stewart died after being arrested by New York transit police, saying it could have been him, and painting the incident. Haring, who painted anti-South African apartheid posters, shared Basquiat’s outrage over Stewart’s brutal bashing, and wrote of being ashamed of his white forefathers: “I’m sure inside I’m not white. … I’m glad I’m different. I’m proud to be gay. I’m proud to have friends and lovers of every colour.”

Both artists disdained the art world for its greed – Haring wrote of its “corruption” – even as it drove up the prices of their works, while the likes of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, Centre Pompidou and the Tate remained inert in the face of the pair’s phenomenal successes, which was buoyed by celebrity endorsements and rock star-like press coverage. Whether homophobia, in the case of Haring, or racism, in the case of Basquiat, played a part in big contemporary institutions declining to exhibit or collect their respective works is open to conjecture.

“On the one hand, I’m convinced that racism and homophobia were part of the rejections at that time,” says Buchhart. “On the other hand, they were extremely young, in their 20s. It’s very hard for institutions like Centre Pompidou and MoMA to actually buy works from very young artists because it is uncertain if this [acclaim] will stay. Of course, the works were so exceptional and those artists were internationally important. Haring was seen as commercial at the time, although his Pop Shop was very much misunderstood. So, it’s a very strange cocktail of why these artists weren’t let in.”

Haring, whose art was already being extensively ripped off internationally on fake T-shirts, caps and badges set up his Pop Shop in New York and Tokyo to sell official merchandise, although he stridently argued that public accessibility to his art, rather than material profit, was his foremost aim with these shops. Haring argued money itself was not evil, although it could “breed evil” in those who lacked a conscience, yet there was a lack of any reflection or qualms expressed in his journals about creating art for a Lucky Strike cigarette advertising campaign. Haring’s generosity with drawing original pictures for fans, particularly children, is however legendary.

Basquiat created T-shirts and postcards of his art as well as collages to support himself before his fame – he sold a couple of these cards to Warhol, with whom he would in time become an artistic collaborator. In 1984, Basquiat wrote: “A picture I sold to Debbie Harry [of Blondie] for $200 a couple of years ago is now worth $20,000.” Basquiat splashed his fast wealth around, but his money also helped facilitate his descent into heavy drug use. At his death, he left behind 1000 paintings and 1000 drawings.

Artist Kenny Scharf, who says he formally introduced Basquiat and Haring names Warhol as the ‘hero’ for all three of them. Haring and Warhol were said to gossip with one another on the phone almost daily about the art world. “It is hard to imagine what N.Y will be like without Andy,” Haring wrote after Warhol’s death in 1987. “How will anyone know where to go or what is cool?” Art world gossip also bit Haring back, as rumours soon circulated that he had AIDS. Whispers of his mortality seemed merely to prompt Haring to leave a legacy, including art for safe-sex campaigns and tackling ignorance about the disease, before his death in 1990 at the age of 31.

Would Haring and Basquiat be as famous without Warhol? “Both of them would be as important as they are without this friendship, but without Warhol [as an artist], they wouldn’t be here,” says Buchhart, “because Warhol was the one who opened things up: you can be a businessman, you can be a magazine editor, photographer, filmmaker … everything Haring and Basquiat presented came out of this idea of Warhol.”

Haring and Basquiat were as inspired by New York dancefloors as by art history. In Haring, one might detect shades of Rothko, Kandinsky, van Gogh, the colour blocks of Miró and black lines of Léger; in Basquiat, the detritus of Picasso, da Vinci, de Kooning, Pollock and Dubuffet. But both were also club kids, who frequented Club 57 in the East Village and Mudd Club in Tribeca. Haring’s mecca was the Paradise Garage, in the Hudson Square neighbourhood. Haring played the B-52’s and Beastie Boys as he drew; Basquiat danced as he painted, preferring bebop and Ravel’s Bolero. Orbiting pop star Madonna or, in the case of Haring, painting his good friend singer Grace Jones, strengthened each artist’s pop cachet.

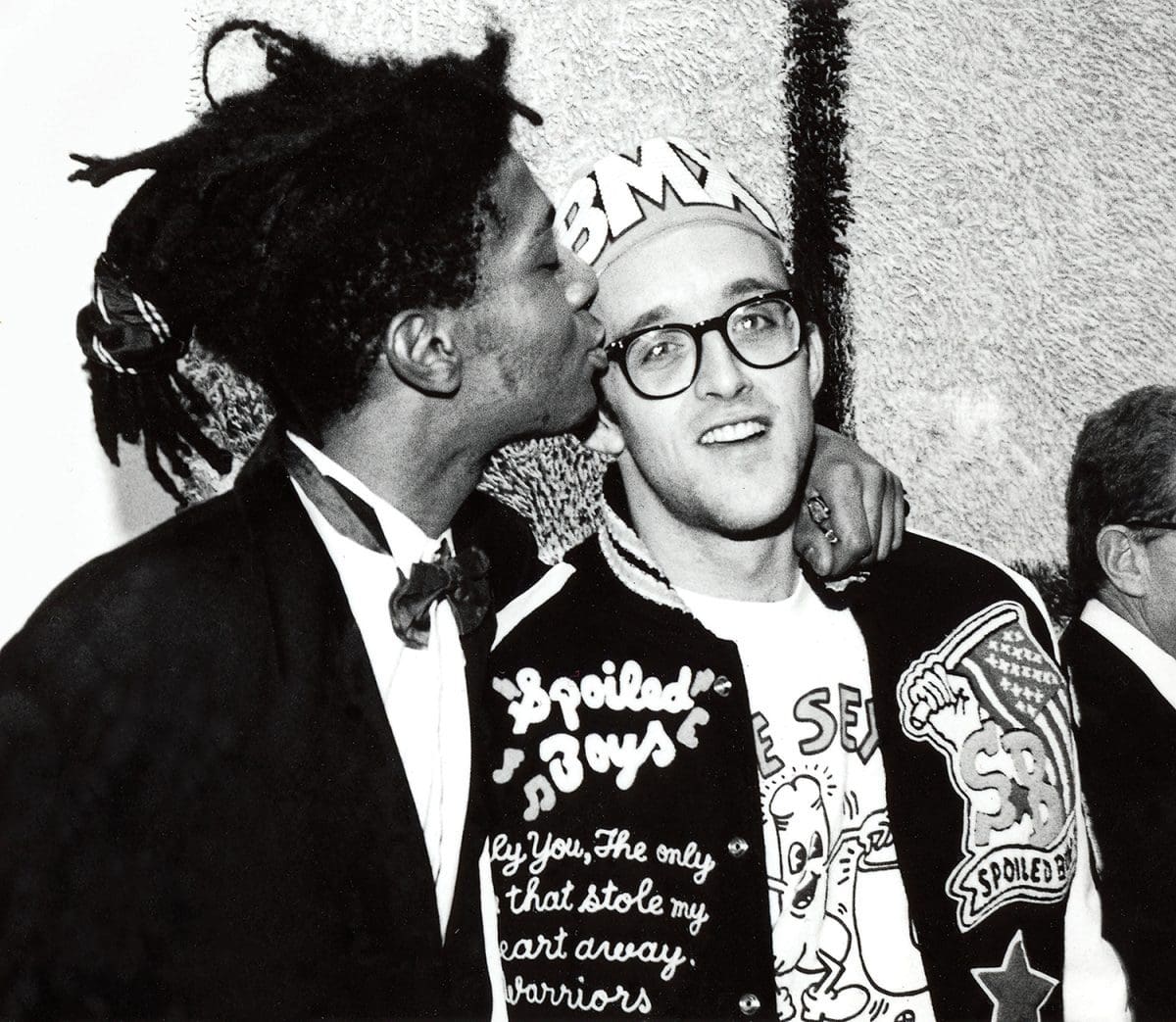

Haring and Basquiat also collaborated; their artworks in 1980 and 1982 delving into slavery and police violence. Haring recalled of Basquiat: “I was always jealous of the attention that he would get in some circles, and he had similar feelings about me for other reasons, so it balanced itself out.” Buchhart says now: “I would say they were friends and rivals. They took two paths, which crossed all the time. Keith Haring was the pop star, so Basquiat was envying Haring for his popularity, and Haring envying Basquiat for being the king of art. It was a healthy rivalry. The two artists loved each other but … you might interpret that their careers were driven by being rivals in a very positive way.”

Last year, Saatchi Art “celebrated” what would have been Haring’s 60th birthday by blogging about four of its own artists that “echo Haring’s style, approach or vision”. The irony is that Haring wrote disdainfully in his journal that Saatchi “might as well be a bank” and that art investment at that level was “bullshit”. Buchhart names conceptual postblack US artist Rashid Johnson as having “great respect” for Basquiat, working in his own way with black soap, a concept Basquiat introduced as a racial synonym for white soap and perceived cleanliness.

Haring once wrote, “when I die there is nobody to take my place”, and Buchhart agrees that remains the case for both artists: “There are a lot of people who imitate the styles of Basquiat and Haring – in fine art and in street art, they were very influential. [But] for both artists, I don’t see any artist in their direct footsteps.”

Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines

NGV International

1 December–13 April 2020

This article was originally published in the November/December 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.