Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

One of my favourite painting techniques is “scumbling”, an onomatopoeic word that describes a dry brush method where the painter creates feathery motions, building moody colour graduations. This technique finds echoes in Kez Hughes’s process. She layers representations of other artworks and objects to confound ideas of authenticity and originality. Her penchant for formalist painting provides a home to challenge how signifying functions change when an object is transposed into a painting.

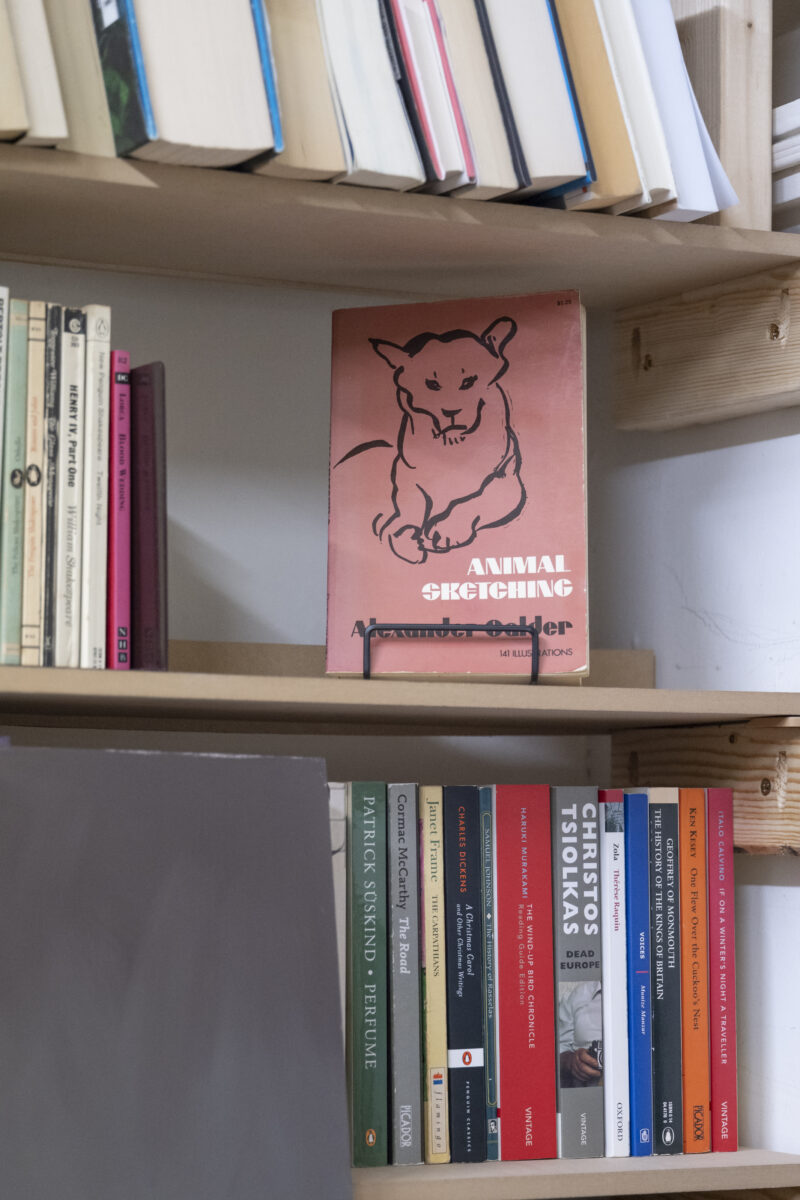

In her studio in Melbourne’s iconic Nicholas Building in the city, which is adorned with 19th-century antique chairs and a Persian rug, Hughes has been crafting meticulous oil paintings that depict ancient objects from European museum collections—all for her solo exhibition Translations at Nicholas Thompson Gallery.

Translations is a departure from her previous pieces depicting artworks made by local Australian artists. It is with deep consideration that Hughes reimagines objects, challenging the relationships that exist between the original artist, the viewer and herself. The act of looking is integral. We are left wondering which of these three protagonists holds the position of main voyeur: what is Hughes looking for? By considering objects of the past, transmuted through the mistranslations and slippages of history, Hughes has found a way to encounter herself in the present.

Kez Hughes: I almost gave it [the studio] up during Covid restrictions and am so glad I held onto it. It’s also where I teach, which allows me to sustain my practice. Our neuropathy for making doesn’t allow us to just flick a switch on and off. Your vision works well one day and not the next.

This is why my studio space is so important. I need time and space to give value to the importance of procrastination, as well as painting. I come to the work in an earnest way. Going through art school in the early 2000s I was heavily influenced by art theory and criticism and have been trained to think about signification. Working as an appropriation artist, this theory becomes necessary. There’s always a sense of remove when the painting is finished, when the “reading” is complete.

Kez Hughes: The act of painting can be likened to the act of consumption. There is this act of consumption, as well as a real reverence and respect for the object I am painting. Much of my work has consisted of painting artworks created by other artists. When painting an artist’s work, I always ask for permission first. The act of copying becomes a type of transcribing or translation.

There are slippages within this process. You’re always going to train by looking to the work of others. This is how things get passed down. We are born into a language which is not our own. We work through structures and frameworks, and how we navigate these spaces becomes how we communicate. Such as how you dress, or what language you speak. You can never fully encompass an object in a painting and things are always shifting.

I work with a diverse range of techniques to build up layers of paint, dependent on the subject I’m painting. There are lots of technical ways that I approach the work, with many techniques for building up layers. It is very labour intensive. When encountering objects or artworks I’m always thinking about how they may translate into a painting. My drive is sparked by the moment when you first encounter an object and it disrupts your thinking. Things coalesce to make the object a perfect image and your brain wants to capture it.

A dear friend recently noted that I turn 3D objects into 2D ones, essentially stripping away a dimension. The essence of the object remains, but it also becomes something else. We [as painters] are in the business of creating images that can hold the gaze for centuries. Elements of composition and colour harmony are crucial for this. Through employing certain painting techniques, I have the opportunity to extend the gaze of the viewer and take it to new places.

Kez Hughes: For Translations at Nicholas Thompson Gallery, I’ve moved away from painting contemporary works by local artists and instead am looking to the past, focusing on objects and artifacts from ancient periods—mainly the Hellenistic period—found in institutions throughout Europe. Some of the objects I have photographed and others I have encountered through source image-banks. The show will consist of 30 paintings. Through looking to these relics of the past, I’m finding space to encounter the more personal within the work.

I feel that I’m connecting more to the body and to emotion through this series. I’m translating these objects and repositioning them as a collection. They are damaged and timeworn. Some are missing arms and legs and the material, usually metal or clay, has become discoloured. These elements allow one to insert the fractious and fragmentary nature of the self into these objects.

When I look at each object I’m interested in how they can emit a feeling or mood. There is often no authorship transcribed to these sorts of objects, just a location. Without a written author, they become their own autonomous thing and as a result there is space for one to find oneself in them.