Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Here in the art world, we like to have concerns: the issues, motifs and stylistic tics that define the outer limits of an artist’s practice. They’re handy; they help us identify the Art Guide cover artist at the newsstand or brainstorm a long list for a themed exhibition.

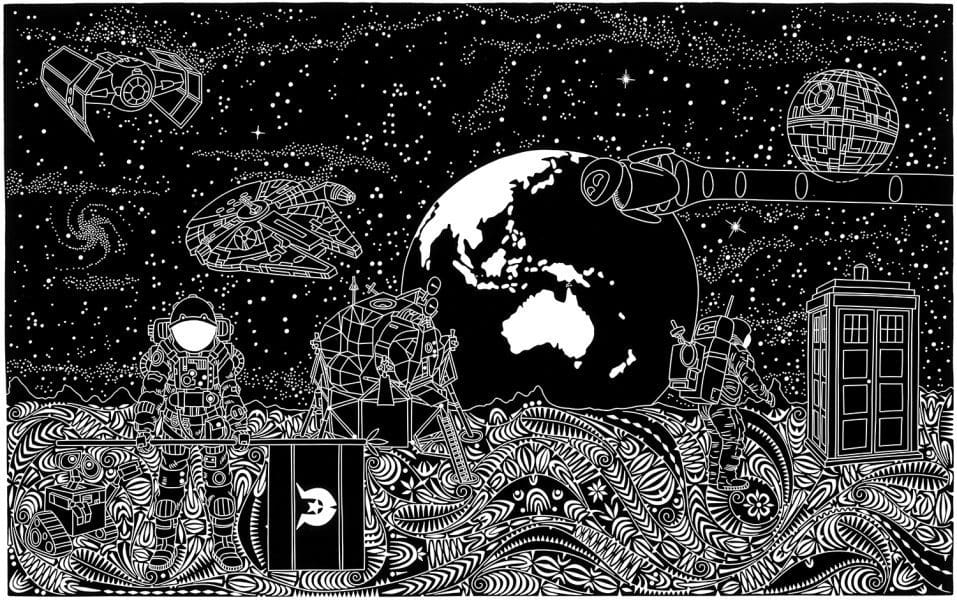

Then there’s Brian Robinson. His unbridled capacity to connect everything allows him to embark from the carving and community traditions of his Thursday Island heritage into Greek mythology, science fiction, origami, colonial history and marine ecology. One imagines it has never occurred to Robinson to cultivate a concern.

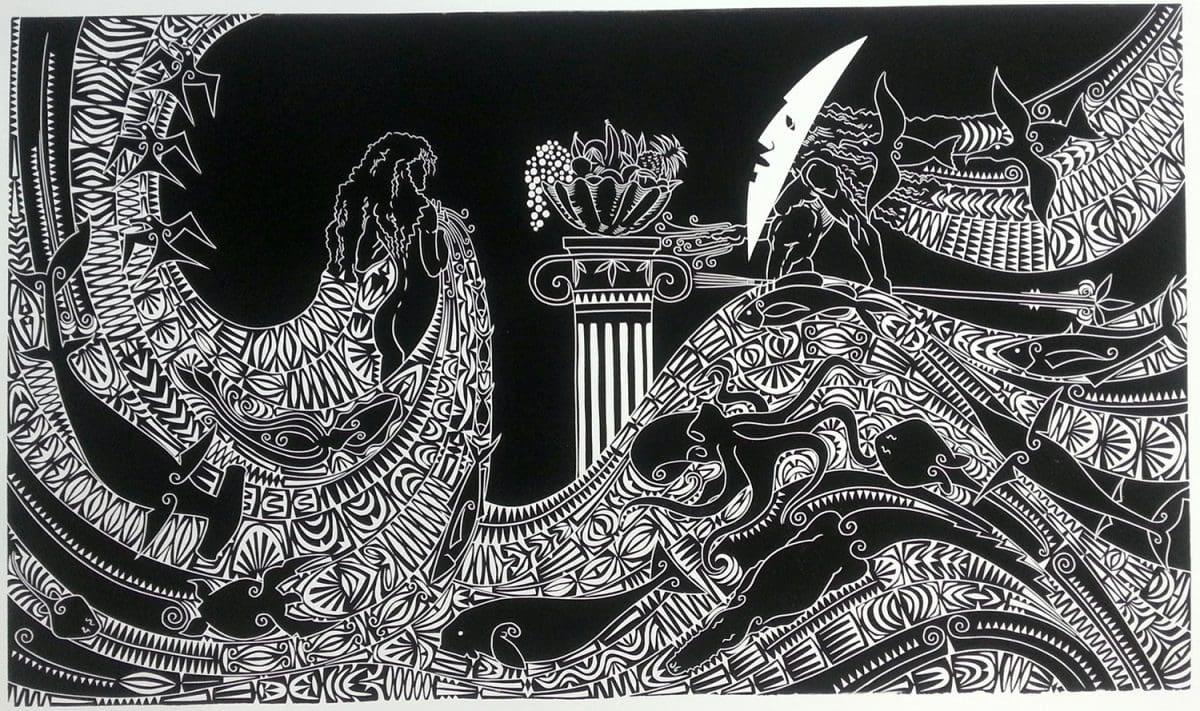

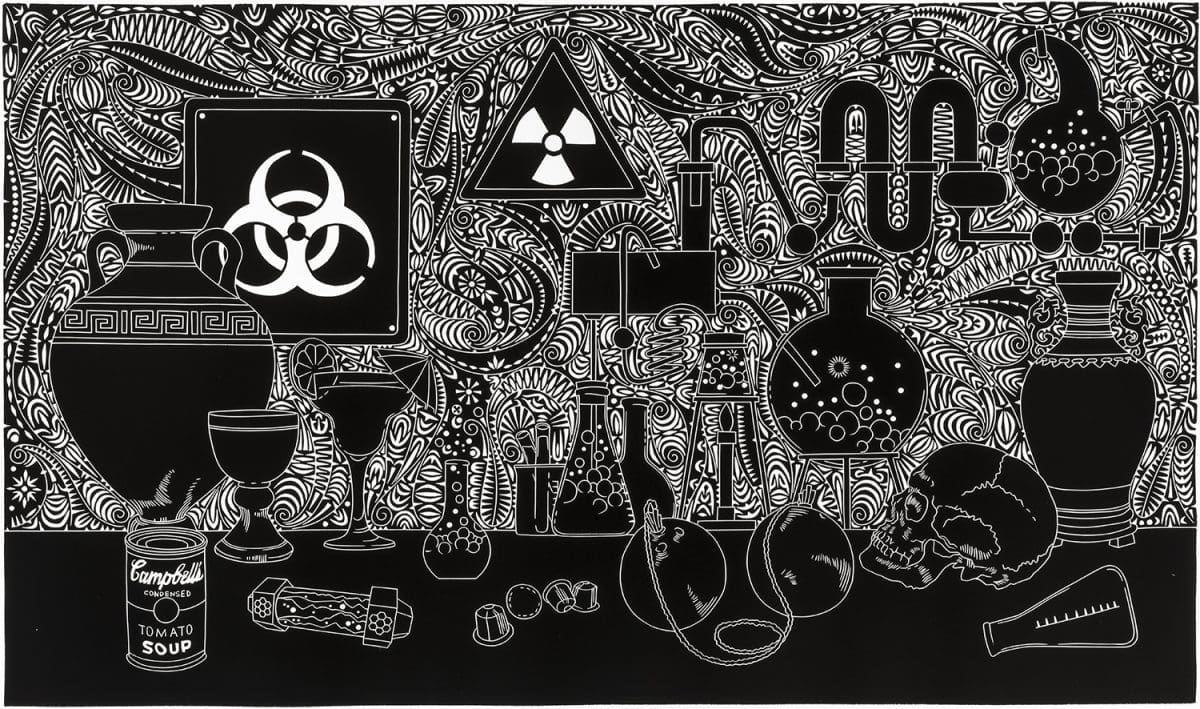

Robinson’s sprawling prints provide a rich snapshot of hunting, fishing and culture in the Torres Strait, spread across 14 of the 274 islands north of the Cape York Peninsula. The masks, vessels, animals and people of this island region drift through richly patterned tableaux. Woven into these contemplations of home are the Cairns-based artist’s view of other worlds: astrological, digital, historical, fictional and art. On the phone, Robinson’s intense and unrelenting hunger for new images, histories and ideas is matched by an equally intense cheerfulness.

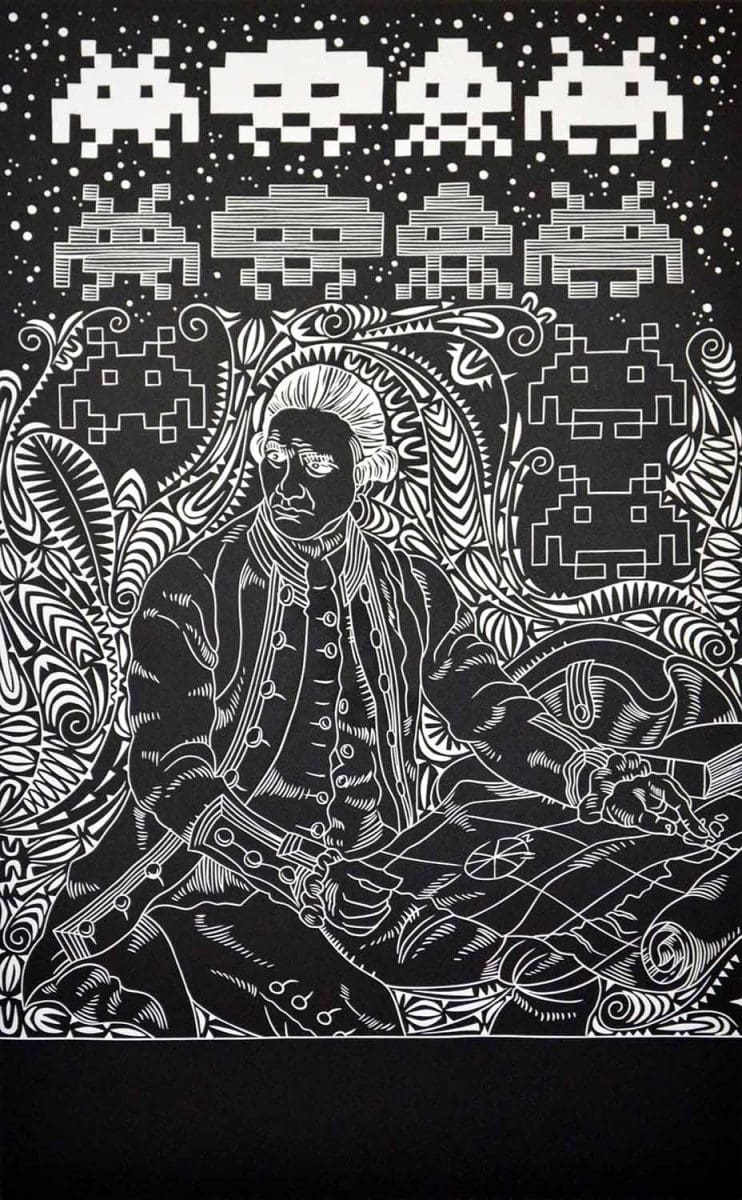

Robinson prefaces his studio time with a stroll through the backyard, his head tilted back to read the maps, calendars and histories in the glittering night sky above. “I’ve been a stargazer for many years,” he says. “I look up and I start connecting the dots. As a child, I learnt about what the stars meant in my community, to navigation, hunting, planting. These same constellations are described in contemporary astronomy and the antique zodiac; in black and white cultures from opposite ends of the earth. It’s an amazing thing to contemplate.”

Tithuyil is a star cluster named in the Kalaw Lagaw Ya language. In the Torres Strait, stars give counsel on all aspects of terrestrial life: agriculture, oceanic navigation, seasonal patterns of animal migration, tides, wind and rainfall. Rather than merely diarising earthly events, “the Zugubal star spirits actually set in motion all the activities that sustain island life. We humans are driven to make sense of chaos. That’s why we group stars, name them and live our lives by their rhythms,” explains Robinson.

The black, nocturnal expanse overhead is Robinson’s tabula rasa from where his theory of knowledge stems. “Monochrome linocut lends itself to celestial mechanics,” says curator Chris Malcolm. “It’s the most immediate thing: you carve a divot into a black field and suddenly you have a twinkling star.” The lineage of Robinson’s cosmological knowledge is ancient, Malcolm explains. A 2018 paper found “no evidence for any way of walking onto this continent. People arrived on vessels from way beyond the horizon. The stars were their only constant source of information. The time it takes to develop that knowledge is mind-boggling. The stars shift minutely, daily, and you have to wait years, generations, to understand the patterns.”

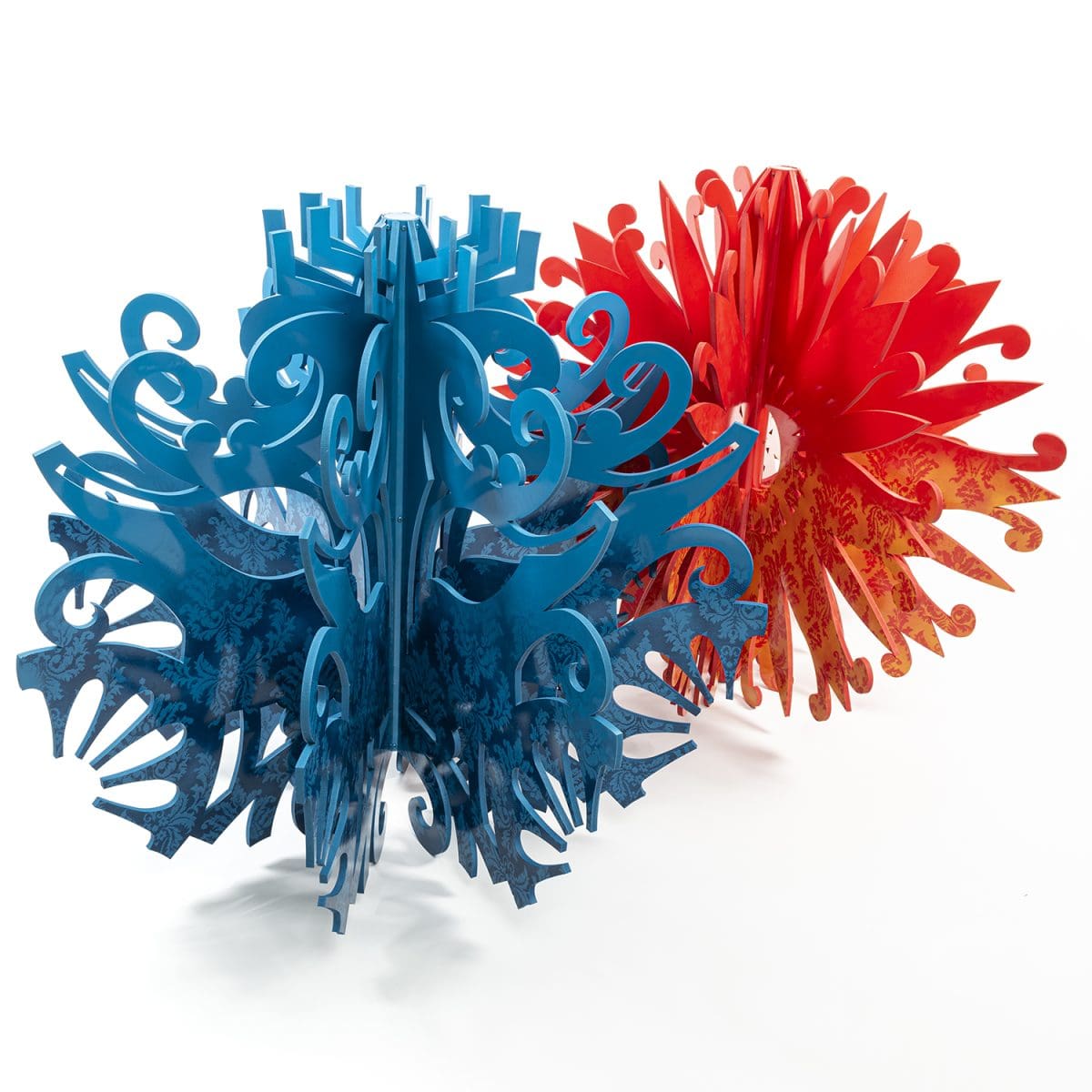

Together with gallerist Dr Diane Mossenson, Malcolm has compiled 53 works from Robinson’s prolific inventory of linocut prints, animation, painting and assemblage. “Every work is outrageously dense,” effuses Malcolm as he prepares the artist’s largest survey to date. “Brian’s gaze knows no boundaries.”

Born in 1974, Robinson’s practice has unfolded access apace with the Internet age. Image and information, says Malcolm has fed his desire “to study things that resonate with his deep sense of his part of the world. Like his ancestors, he’s thinking in vast terms: on-world and off-world; natural and supernatural; universal mechanics. When these same ideas pop up in comics or movies, he brings them in without conflict or hierarchy.”

Carved into scenes of island life, the Millennium Falcon, Astro Boy and Batman’s mask appear not more or less supernatural, nor culturally fundamental, than migrating sea turtles or crescentmasked dugong hunters. After all, science fiction and island lore share the same marvellous proportions and storylines, flowing from a common human impulse for epic narrative. On this train of thought, I ask Robinson what star cluster would make the best big-budget blockbuster.

“Ah, the story of Tagai! Tagai is warrior and voyager, known to all Torres Strait Islanders. He’s a constellation, made up of the Southern Cross, Scorpius, Lupus and Corvus. He sets sail on his canoe, brandishing a fishing spear and a handful of fruit, all alone because he has thrown his crew into the sea. Our stories are powerful; all love and hate, blood and guts!”

Like any single print of Robinson’s, Tithuyil presents the world through the artist’s inner schema. “He’s no bowerbird,” says Malcolm, “he’s a librarian, a world archivist. He carves for hours, each work the culmination of a long, meticulous train of thought.” Or as Robinson puts it: “there are countless things colliding around in the universe, and similar things collide around in my old noggin’.”

Brian Robinson: Tithuyil (Moving with the rhythm of the stars)

John Curtin Gallery

6 October—8 December

This article was originally published in the November/December 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.