Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Nicholas Mangan, A World Undone (video still), 2009-10, single-channel HD colour video, silent. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Matter over Mined, 2012, c-type print on cotton paper. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table, 2009-10, coral limestone from the island of Nauru, Michael Buxton Collection, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Mined over Matter (for A World Undone), 2012, c-type print on cotton paper. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth, 2016, 4-channel CCTV live camera stream, single-channel, HD colour video, sound, hand-printed c-type photographs, installation view, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2016. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

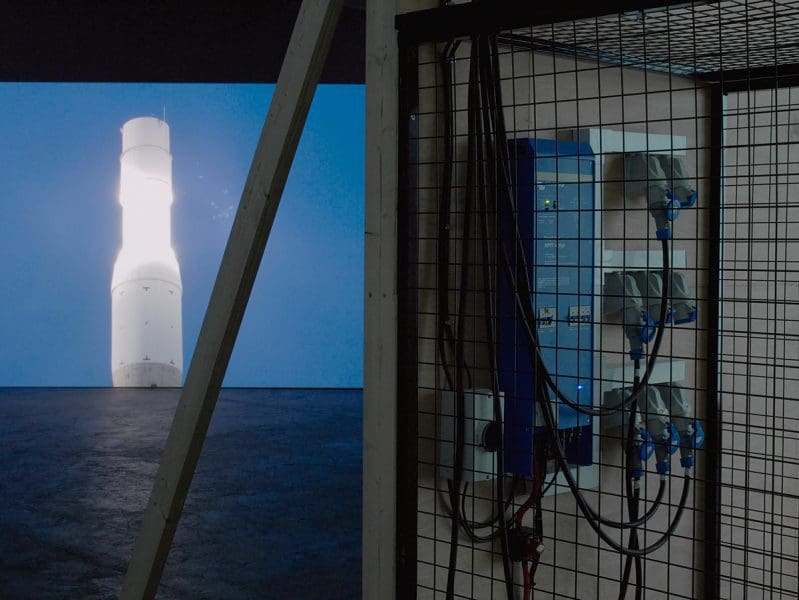

Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth, 2016, 4-channel CCTV live camera stream, single-channel, HD colour video, sound, hand-printed C-type photographs, installation view, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2016. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth, 2016, 4-channel CCTV live camera stream, single-channel HD colour video, sound installation view, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2016. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights, 2015, two-channel HD colour video, sound, off-grid photovoltaic power supply installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, London co-commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery, London, and Artspace, Sydney. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth, 2016, 9 Terrahash bitcoin mining rigs, installation view, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2016, Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan, Progress in Action, 2013, single-channel HD colour video, silent, converted diesel generator, provisional coconut oil refinery, coconuts installation view, Mercosul Biennial, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2013. Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland; and LABOR, Mexico City, D.F.

Nicholas Mangan’s practice mines themes of extended time, the geological periods that we try to define but can’t quite grasp, and the impacts of capitalism on the environment. Sarah Werkmeister spoke to the Melbourne-based artist about his love of rocks, the power of the sun and making art in the age of climate change.

Sarah Werkmeister: Where did your interest in geology come from?

Nicholas Mangan: There are two things. Ultimately I’m coming from a sculptural practice, so it’s always about understanding where materials I use come from, and then privileging the history of that material even before it turns into a particular object of significance. There’s also the fact that my grandfather was the manager of the Geelong quarry, and he had crazy rock collections and I soaked it up subconsciously.

My work often occupies the durational in one way or another, considering things in a geological time, or the way that the world itself is a process of flows and transformations.

My practice addresses how the extraction and refinement of raw material effects the social domain. The geological has been at the mercy of the so called “great acceleration” and late capitalist extraction. It has also been at the core of ongoing issues around the changing climate. The climate change debate at the top has become a very intricate web of double speak. First we started with green-washing, where corporate companies gave the impression that they were cleaning up their act, and more recently, the whole language has transformed, but the actions haven’t. It’s important to acknowledge there are now some real disruptive innovation technologies that are implementing change.

SW: You see that more and more with the progression of capitalism into this accelerated form where technology is buzzing and those with power are talking, but not much is changing. It’s in your show title as well, Limits to Growth…

NM: Yes, the show title is taken from the book written by these technocrats and scientists in 1972, called The Limits to Growth. At the time the book was highly disputed because they used a computer modelling system called World3 based on system dynamics and feedback loops to calculate what shape the world would be in if the trajectory of expediential growth and consumption maintained it course. At that time, the computer may not have had the agility needed to measure such complex data, however, the results were devastating. The book became an international best seller and triggered the public’s imagination about the idea of limited growth and what the broader implications of unmitigated progress might actually mean. Now people are starting to look at this study again as it’s undeniable that we have reached our limits.

Each of my works included in my Limits to Growth exhibition function like overlapping ecosystems. With the Nauru project, Nauru – Notes From a Cretaceous World, 2009-2010, it’s also about agriculture through phosphate mining and exploiting one land mass to feed a growing empire elsewhere. The Bougainville work, Progress in Action, 2013, is about one of the first successful resistances against a multinational corporation who was exploiting the people’s land and way of life.

Ancient Lights, 2015, deals with solar energy, exploring Bataille’s idea of the general economy, where he states that we receive energy from the sun without having to pay for it but that energy gets absorbed into every aspect of our lives resulting is surplus, There’s more energy than is useful and somehow it must be spent, whether gloriously or catastrophically. I was thinking about how solar is the ultimate free energy. I also started reading about Alexander Chizhevsky, who was a Russian biophysicist from the early 20th century who was looking at the 11 year cycle of the sun in relation to the human psyche. He claimed the sun was capable of amplifying human behaviour.

There is a particular school of economists who’ve looked at this in relation to business/recession cycles. It’s highly speculative but it’s also something that’s physical and visible: we understand that the sun is responsible for the whole of the earth. The project, Ancient Lights, 2015, looks at how humans refine and harness the potential energy of something like the sun, but it also questions whether the sun has its own agenda and its own potential agency.

SW: How do you think art can actually tackle mass geological change or climate change?

NM: If you can show people something in a way that they haven’t seen it before, that can provide a sense of transformation. If an artwork can use its agency to stimulate the senses in any way, and open up space in people’s thinking to allow new connections to be made, then that’s great. I’m not at all interested in art about art, but more interested in using art for self education.

Nick Mangan: Limits to Growth

Institute of Modern Art (IMA)

29 October – 18 December