Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Artist-run and experimental spaces are central to the story of Australian art, giving emerging and barrierpushing works a place to be exhibited. While scores of such spaces exist throughout Australian art history, we asked five artists to tell us about their early works in experimental spaces and how these formative experiences became pivotal to their practices. At a time when the resourcing of such spaces is in constant jeopardy, these artists show the necessity of non-institutional exhibiting.

Bonita Ely

After five years overseas in London and New York, I returned to Australia in 1975. A report on the Murray River was released which detailed salination and other pollutants, motivating me to draw people’s attention to the river and its imminent degradation by ‘taking them there’—not everyone can drop everything to travel 2,108 kilometres, observing, exploring, making art.

Brought up on the Murray in the soldier settlement town of Robinvale, the river is my ‘Heartland’, so to speak. With summer temperatures in the 30s and 40s, families cooled down in the river, picnicking nearby, kids playing together until after dark.

When invited to participate in the performance event ‘Women at Work’ at the Ewing and George Paton Galleries, Melbourne University— asked by Director Kiffy Rubbo and curator Meredith Rogers—I also coincidently saw a cooking demonstration in the Myer department store, a novelty back then.

My mind flipped into parody mode, conjuring the performance; I dressed demurely, delivering charming chit chat commercialising housework, while cooking up a disgusting, stinking brew titled Murray River Punch (pun intended). The next year the performance was repeated in Rundle Street Mall in Adelaide. Received with groans, laughter and horror to my delight, it foreshadowed the environmental disasters to come.

David Chesworth

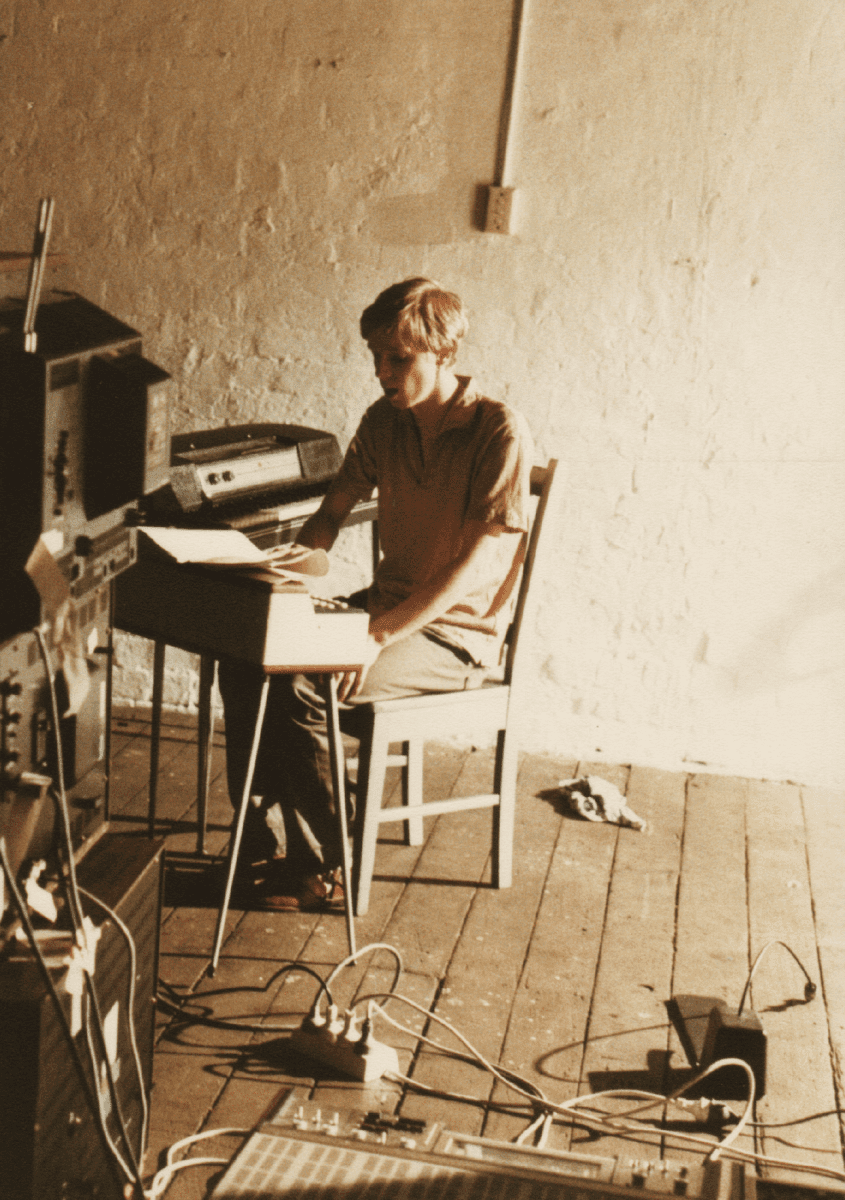

Running from 1976 to 1983, Clifton Hill Community Music Centre (CHCMC) was a community-founded experimental music venue located, rent free, in an old organ factory in Clifton Hill, Melbourne. It was indirectly assisted by the Whitlam government’s support for community projects and took off because punk and post-punk inspired a ‘just do it’ attitude, and audiences and makers began to coalesce around nascent sub-cultures that ignored the mainstream.

It was a lively place where artists from two distinct generations created, performed, debated and occasionally shirt-fronted each other. In the small rooms of the organ factory, an emerging postmodernism rubbed up against counterculture aesthetics. Boundaries of performance, music-making, filmmaking and installation were dissolved. Musicians made films, visual artists made music, critics and theorists performed.

Importantly, artist Ron Nagorcka made the events free and artists received no payment. The performers and audience were on an equal footing, where anyone could perform, often utilising cheap and available technologies, rather than traditional instruments. It was a place to begin, trying anything we wanted. It was also where I mustered the courage to perform for the first time, both as a solo artist and with the minimalist music group Essendon Airport, alongside coordinating the venue between 1978 to 1982.

Paul Taylor, who founded the art journal Art & Text, was a frequent visitor, even presenting a work. In 1982, Taylor’s breakthrough Popism exhibition at National Gallery of Victoria would feature many CHCMC artists.

Michael Lindeman

Toward the end of my undergraduate in the late 1990s, I founded Michael & Michael Visual Arts Project Management with Michael Dagostino. With a healthy dose of irreverence and a DIY philosophy, it was a serious joke—an artwork itself. Key to becoming productive irritants while having fun were artist-run spaces around Sydney and interstate such as First Draft, Herringbone, Rubyayre, 151 Regent St., Grey Matter and Smith & Stonely.

Pooling our resources with artists including Paul White, Jonathan Wilson and others, artist-run spaces allowed us to gain experience with all facets in developing a show—guerrilla style promotion, considering the exhibition space, baiting critics (got some good nibbles from the Sydney Morning Herald), and discussing one’s practice. I have no doubt that certain people around town still hold a grudge for our deadpan aping of institutional models and unmasking of their barriers. Nonetheless, it was entertaining, ballsy, and illustrated an aversion to passive compliance—that’s a good thing, right?

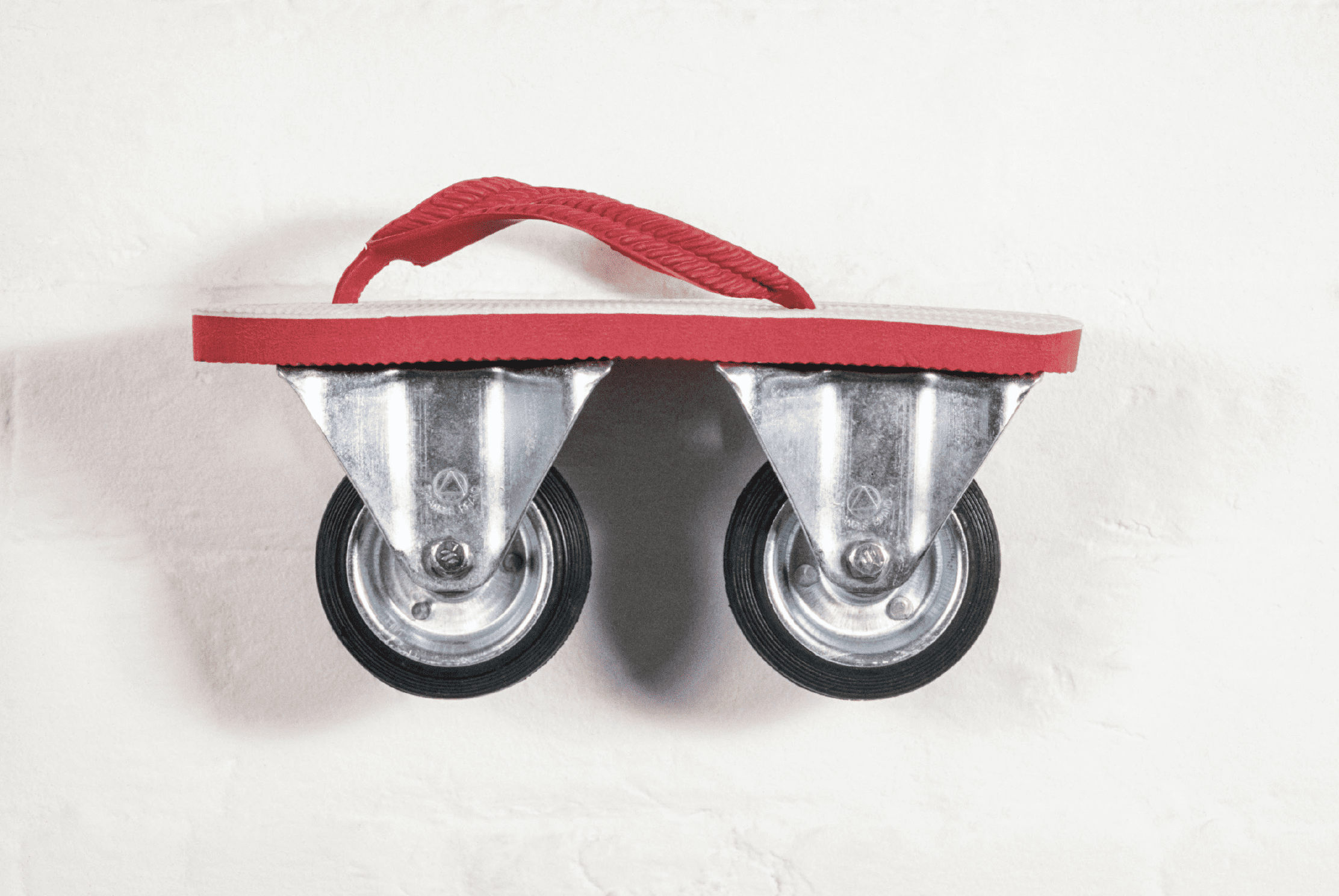

Alongside cultivating an environment which agitated systems of inclusion and exclusion, the non-institutional spaces gave me licence, a freedom to develop a series of absurd Duchampian rectified readymades—dictated by a student’s budget and my prosaic surroundings. The wit and attitude of my formative works, facilitated by artist-run spaces, continues to reverberate throughout my work today.

Kenny Pittock

In 2013 a friend and I put on a show at the Naarm/Melbourne artist run gallery TCB. For the exhibition I created ceramic sculptures of the contents of a Bertie Beetle showbag, and also gave out free actual Bertie Beetle showbags to the first 50 people who came to the gallery. The Italian arts writer Naima Morelli happened to see the show and amazingly the following year she invited me to travel to Italy for an exhibition at Galleria 291 Est, an artist-run gallery in Rome.

It was my first time exhibiting overseas and a big step for my career at the time. As a lot of my work responds to contemporary Australian culture, I was excited for the opportunity to exhibit outside of this context. It was so special to see how people on the other side of the world, who, despite our language barrier, were able to laugh and connect over the work.

I’m grateful for artist-run galleries for giving me the platform that allowed my first experience exhibiting in an international context. It helped me consider ways my practice can be global while also remaining personal—an insight that still plays into my work today.

Diego Ramirez

One of my ‘signature moves’ is to consider the social coding of my position in the arts and upset its meaning within a virtue economy. In other words, I am very sarcastic. Artist Mel Deerson, after an original commission by the online platform Recess, helped me develop this sensibility in 2019, when she asked me to participate in A night in Hell, a public program to her show A show about hell at Kings ARI in Melbourne.

She curated a series of performances to activate this huge medieval backdrop she created; it was like a stage. It’s Deerson’s angelic pattern to appear every couple of years in my life with grassroots energy, then momentarily disappear to become the light in someone else’s dark world.

Thanks to her appreciation, I performed Once More, With Diversity Feeling, an ‘audition’ for a Mexican vampire in the canned Buffy The Vampire Slayer reboot, which was promoted as emphasising diversity. Inspired by novelty acts, I sang pitchy songs with over-the-top lyrics—like a goth softboi—hoping to get ‘cast’. The audience wanted to laugh at me but didn’t want to be ‘problematic’. This kind of perverse tension is now a staple in the push and pull that characterises my output.