Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Sam Jinks, Woman and child, 2010 (detail), silicone, silk, human hair, Collection of the artist.

Patricia Piccinini, The welcome guest, 2011, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, clothing, taxidermied peacock. Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco.

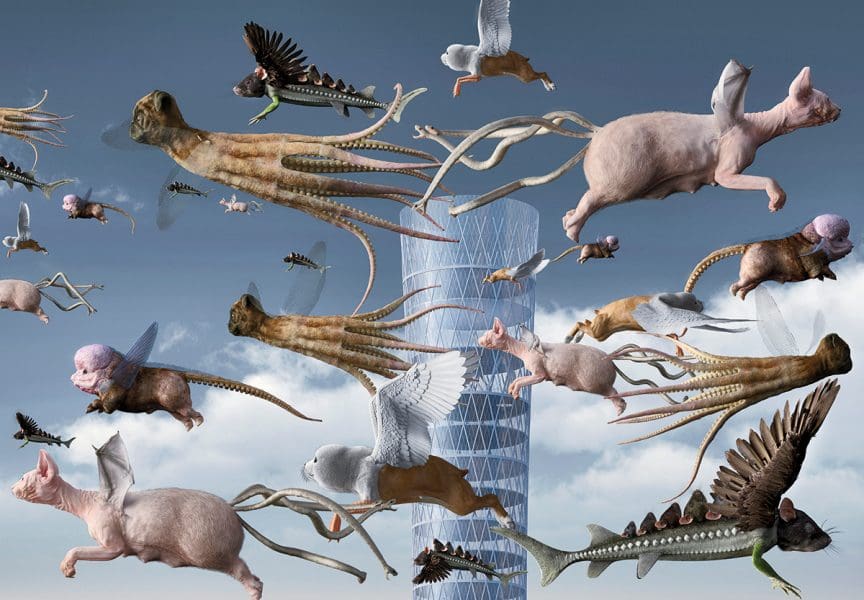

AES+F, Inverso mundus, 2015, HD video installation © AES+F | ARS New York, Courtesy the artists, MAMM, Anna Schwarz Gallery and Triumph Gallery.

Patricia Piccinini, Eulogy, 2011 (detail), Warwick and Jane Flecknoe Bequest Fund 2015, Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco.

Patricia Piccinini, Newborn, 2010, Collection of Paris Neilson. Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco.

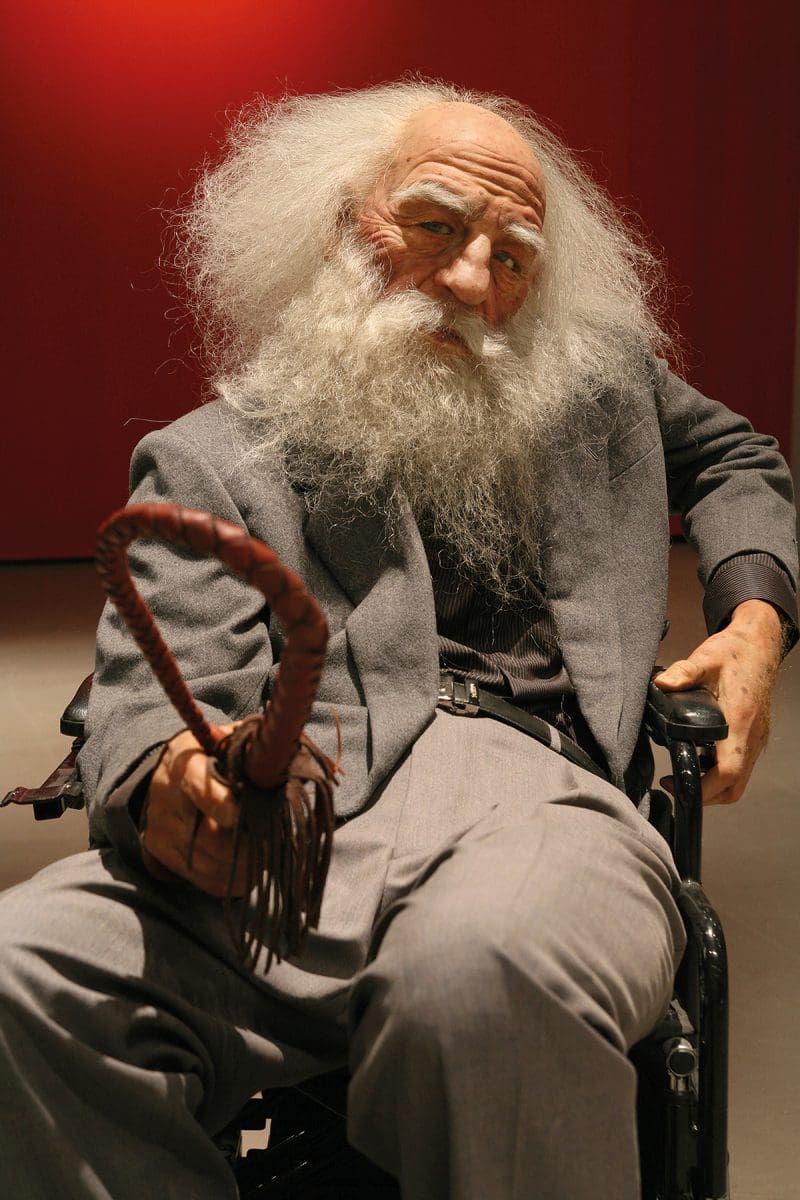

Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Old people’s home (detail), 2007, electric wheelchairs, fiberglass, silica gel. Courtesy of the artists.

Hyperrealism emerged in the 1960s when artists began to use newly developed materials and technological advancements to create exceptionally lifelike sculptures. Like the overachieving sibling of photorealism, hyperrealism extended our voyeuristic fascination with the human visage into the three-dimensional realm. As skin, hair, posture and facial expressions were reproduced in such detail, it became difficult to discern the actual from the synthetic. From uncanny portrayals of humans performing everyday tasks to fantastical depictions of futuristic creatures, hyperrealism uses advanced sculpting techniques more akin to the special effects industry than the visual arts, to create works that meticulously reflect reality.

Exhibited among many others, are works by early American pioneers George Segal, John de Andrea and Duane Hanson, Belgian artist Berlinde de Bruyckere, provocative artist and publisher Maurizio Cattelan and digital artists Cao Fei and Tony Oursler.

The exhibition also includes a number of sculptures previously displayed in Spain, Denmark and Mexico as part of Hyperrealism 1967-2013, an international touring exhibition curated by Otto Letze, Director of Germany’s Institute for Cultural Exchange. For Hyper Real, NGA senior curator Jaklyn Babington has specifically chosen works that ponder humanity’s biggest question – what does it really mean to be human?

Responding to this question, the artists in Hyper Real have used materials like colour pigmented silicone, human hair, animal hide, resin and digital media to produce their work. Ron Mueck’s sculptures of human figures immediately stand out for their immense scale and emotive faces, often dwarfing viewers who linger beside them. Despite their size, the scale of Mueck’s figures renders them strangely vulnerable as they stand alone in the gallery space. By amplifying the everyday, Mueck connects to our own sense of vulnerability, as we become silent witnesses to a private exchange or solitary moment.

Beside Mueck, Babington has included several other Australian artists working with hyperrealist techniques. Sam Jinks draws on his background as a model maker in the film industry to create sculptures like Woman and child, 2010. In this tenderly detailed work, Jinks presents an elderly woman cradling a newborn. The gently weathered skin of the woman complements the wrinkles of the baby and together they each represent a bookend of the life cycle. “Having a baby and an older woman [together], it’s really the same individual,” Jinks says. “It’s a nice way of balancing it so it’s not a literal scene, it’s a bit more abstract.”

Rather than imitate a direct representation of reality, Patricia Piccinini and Russian artist collective AES+F mutate the familiar to create biologically altered life forms that push the boundaries of evolution and possibility. Originally presented at the 2015 Venice Biennale, AES+F’s Inverso Mundus 2015 is a multichannel video project featuring a wildly theatrical vision of hybrid animals and futuristic urban environments. In a similar way, Patricia Piccinini’s work focuses on genetic mutations that question what we view as normal. In Newborn, 2010, the potential of alternate life forms is expressed in the nubby, tentacle-like limbs of a tiny human hybrid, an arresting visual contrast to the familiar human figures of Muek and Jinks.

Previously seen in Australia in 2012 in the ACCA solo show, We are all Flesh, de Bruyckere’s sculptures are both uncomfortably familiar and abstractly sublime. Often assuming the contorted shapes of horses in death throes or long, sinuous rolls of headless forms piled into strangely mesmerizing amalgamations of flesh, de Bruyckere’s works are deeply visceral accounts of tangled beauty.

Using specialist materials to create lifelike figures allows for broad conceptual possibilities and many of the works in Hyper Real possess a filmic quality, appearing like characters who have momentarily stepped from a bizarre alternate universe into our own. Embodying the core themes of hyperrealism, Canadian sculptor Evan Penny works primarily from observation and has contributed special effects to films like Natural Born Killers and JFK. Speaking about his practice at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2012, Penny said, “I regard myself as an ‘ambivalent portraitist’ and it is in part because I’m more interested in the question of observation. The question of identity, rather than to affirm or assert it. There are many crafts and many aspects to the process that one has to master and pull together. Maybe that’s the hardest thing of all, to make sure all of the things are up to a certain standard so at the end, they all come together. There won’t be one part that is so obviously weaker that you are not convinced.”

Hyper Real

National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Canberra

20 October – 18 February, 2018