Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

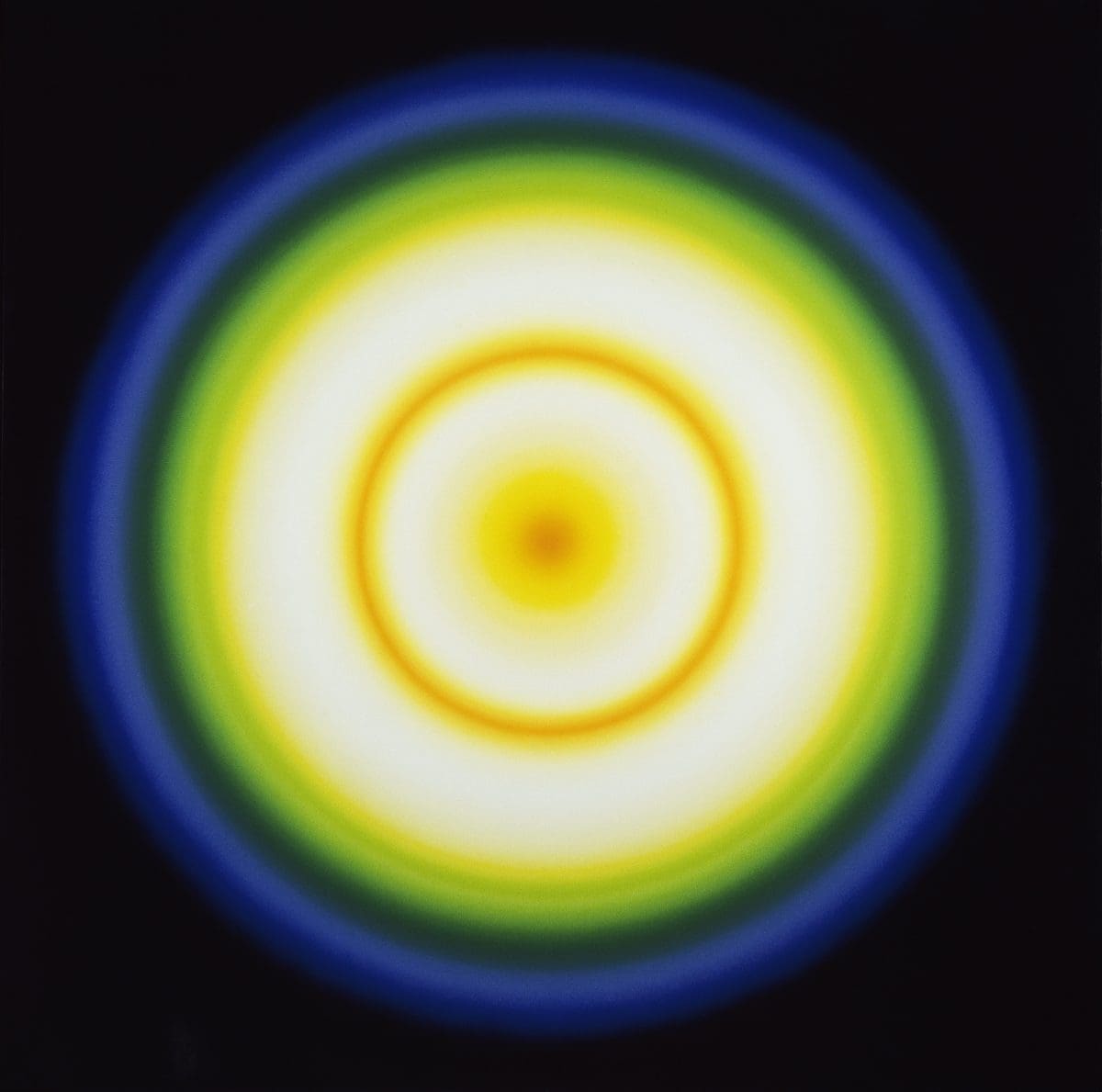

The American poet Diane di Prima writes: “Extract the juice which is itself a Light.”The oscillating electric field of light has long held the attention of artists. Light: Works from Tate’s Collection is a major new exhibition at ACMI tracing the history of how artists in the Tate’s collection have engaged with light for over 200 years.

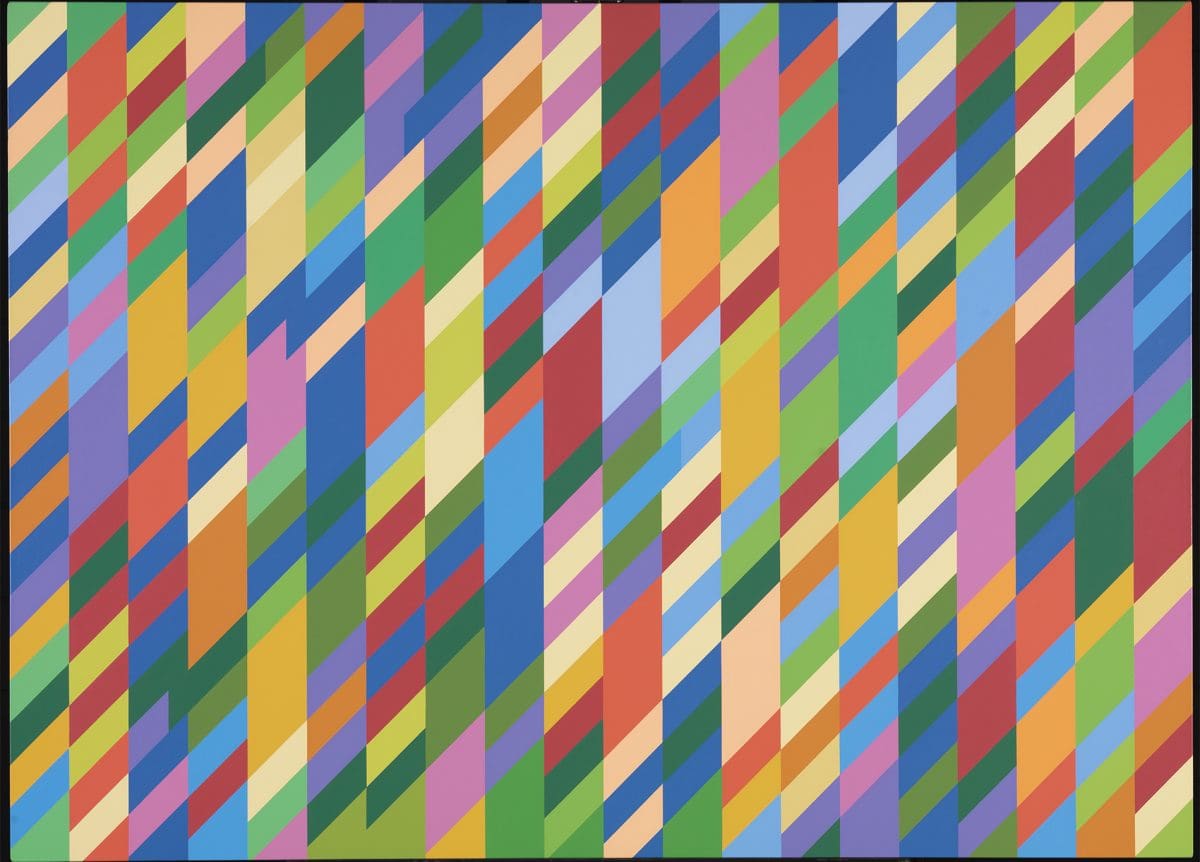

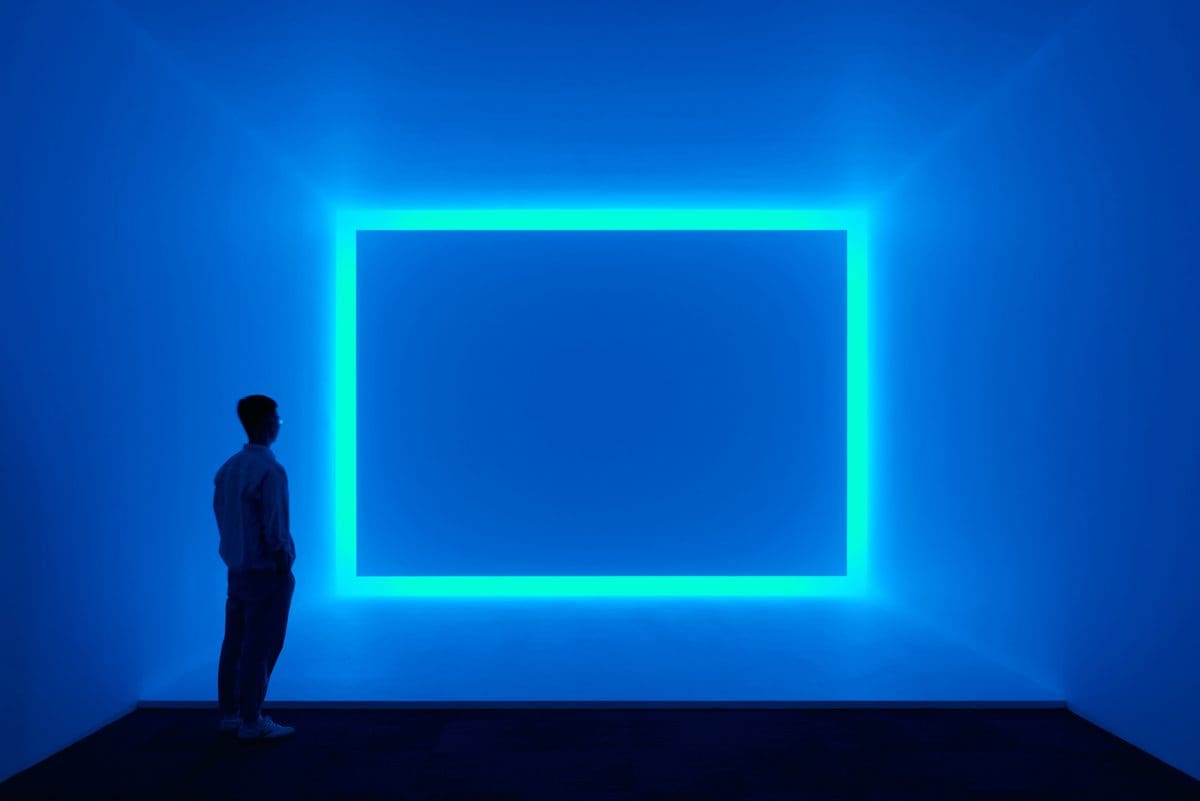

Featuring more than 70 works across painting, photography, sculpture, kinetic art and installation, the exhibition reveals how light transcends historical boundaries and forms. Evolving from the 19th century, with paintings including The Deluge, 1805, by celebrated Romantic painter J. M. W. Turner, along with other Romantic artworks by John Constable, made with his collaborator, David Lucas. These works are contrasted against contemporary expressions by artists such as Tacita Dean, Olafur Eliasson and Yayoi Kusama.

The luminescence of light reflecting against varied surfaces is the pulsing force uniting the exhibition. As ACMI curator Laura Castagnini explains, the show “creates somatic connections across time”. But there’s also attention to how “the phenomenon of light has pushed artists to make work in different mediums . . . Turner’s representation of light in the sky pushed him forward in his thinking and his practice in the same way that other exhibited artists like Dan Flavin began making sculptures out of fluorescent light bulbs in the 60s.”

Artistic interpretations of light are crucial when it comes to influencing how light is culturally perceived and appreciated, with new technologies further progressing these interpretations. “Oil paint was once a new technology at a certain point in history,” states Castagnini. “The different mediums used to represent light are important to acknowledge when it comes to concepts such as cinema.”

Lis Rhodes work Light Music, 1975, is an example of expanded cinema. Rhodes was part of the London Film-Makers’ Co-op, founded in 1966, and a feminist artist transgressing the social limitations placed upon women, particularly in film. As Castagnini explains, Light Music “draws a score onto the film strip and the images viewed are the sounds that you hear. It’s like a correlation, and when you are witnessing the work, you become part of the work. It’s an exciting example of experimental film as a new technology.”

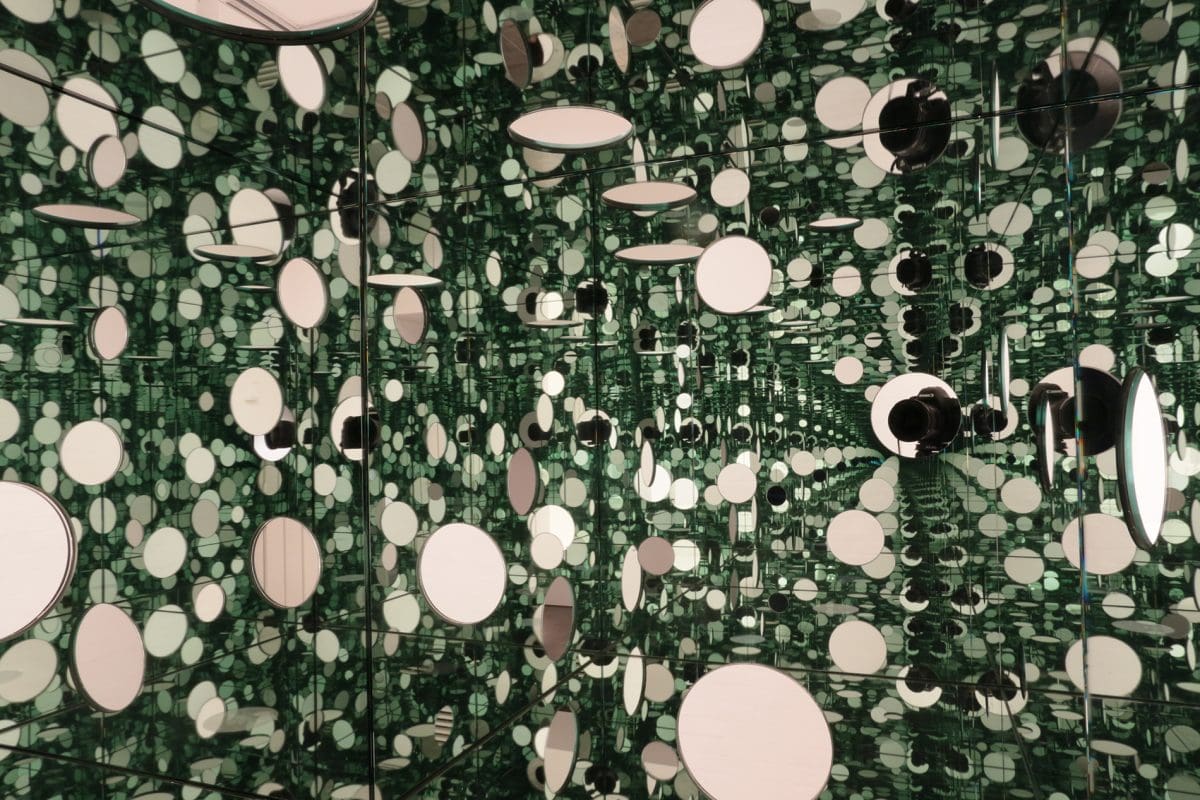

Meanwhile Kusama’s installation, The Passing Winter, 2005, captures how light can alter our perceptions of our surrounding environment—and interestingly Kusama’s sculpture will be situated alongside Impressionist paintings. “You might question why these works are positioned together,” says Castagnini, “but it makes so much sense because they’re both interested in the way light reflects upon specific substances. The Impressionists were interested in the way light bounces off water and how this causes an effect—yet Kusama is interested in the way that light reflects off mirrors and what kinds of consequences this has for the viewer.”

“When you gaze into Kusama’s sculpture you will see the room reflected back at you, especially the other works in the room, so you’ll see a kaleidoscope of Impressionists,” says Castagnini. This interpretation evokes Liliane Lijn’s description of her exhibited installation Liquid Reflections, 1968, to be “a cosmic model not only in the metaphorical sense of being reflections within reflections, circles within circles and spheres within spheres but also through a demonstration of forces.”

Light: Works from Tate’s Collection

ACMI

16 June—13 November