Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Ian Tully, The Diviner, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Ian Tully, Farnley, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Olivia Tully-Watts.

Ian Tully, Future farming: The Mars Project, installation view, Wagga Wagga Art Gallery, 2019. Image courtesy Wagga Wagga Art Gallery.

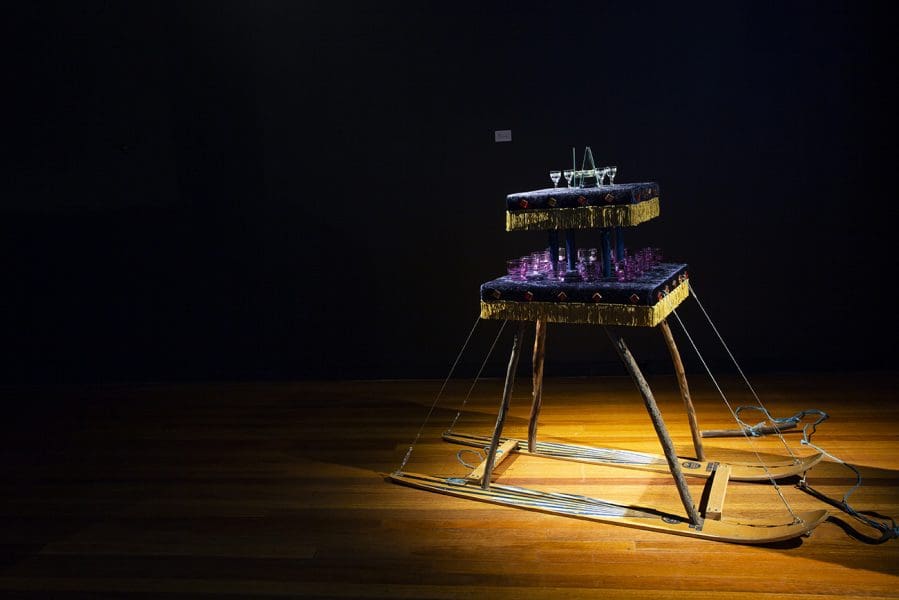

Ian Tully, Future farming: The Mars Project, installation view, Wagga Wagga Art Gallery, 2019. Image courtesy Wagga Wagga Art Gallery.

Ian Tully, Future farming: The Mars Project, installation view, Wagga Wagga Art Gallery, 2019. Image courtesy Wagga Wagga Art Gallery.

Ian Tully is an artist from the border region between NSW and Victoria. His solo show Future Farming: The Mars Project is informed by his agrarian upbringing. Tully’s work considers a future made uncertain by climate crisis from the perspective of rural life. His constructions and performances use deadpan ingenuity to propose rituals and model quasi-practical responses to impending change.

Rebecca Shanahan: Your work is rooted in your experience of life in a small Australian farming community. Where does Mars fit in?

Ian Tully: It’s the next move for the [imaginary] farmer character this show is about. My farmer has been frustrated with the state of things for some time and is looking to move.

It’s a response to the decline in services across regional Australia and the whole gamut of factors that are making the farmer’s existence, and those of a lot of other people, more difficult.

RS: I’m hearing a kind of science fiction quality to this, a kind of prepper quality. Is it an evacuation?

IT: It’s not so much an evacuation as the next possibility for my farmer to work on. Sometimes people sell up and move where the climate is better and it suits their farming practice more. So maybe Mars is that next frontier for this person. Mars is untouched, so this is where this farmer could establish production.

RS: Does that idea have any relation to Australia’s history of colonisation?

IT: Not so much. It’s more personal. I’m reflecting on the people that live and farm in the regions, using myself and my family’s experience as a resource for information.

RS: As an artist who grew up on a farm, how has climate change informed your practice?

IT: We’ve been aware of environmental degradation for decades and it is a concern and source of conflict for me. Growing up on a farm where the whole idea is to exploit the land, I was always conflicted.

Climate change is just a further exacerbation of how we make some sort of existence. How do we reconcile the fact that we need to feed everyone? There’s negative press about people who work in agriculture, but there are people adapting and using the best technology.

One example is developing new varieties of wheat or rice with shorter growing periods (because there’s not much rain) which are sown and harvested within a short time. There’s a lot of technology and smart thinking in response to climate change.

The negative side is, of course, areas of the country that are drying up. There is going to be climate migration at some stage. It’s happening already elsewhere, but it’ll be brought into sharp relief here in Australia. Imagine if Tamworth or some of those bigger country towns dry up and people have to move.

The history of sourcing water has been an integral part of our family’s history. We’ve been through a number of droughts. There are photos from the 1960s when we sank the first bore on the farm. That evidence manifests in this work as well. There are several layers: farming, the rural aesthetic, conflicts and issues in environmental degradation, the all-consuming climate change we are experiencing.

RS: How did the shift in your practice to sculptural models and prototypes, and the accompanying performative work, develop?

IT: I started making small assemblages and thought there wasn’t much point having it sitting on a plinth or attached to a wall; it needed to be activated. I wanted to connect with the landscape. The white cube is fine but I needed to put myself in the landscape.

RS: There’s a kind of soldier-on, tragi-comic, make-do-and-mend quality to your constructions and performances. What has inspired this?

IT: The farming community is very creative because they have to be. My father and brother were always making things, adapting them.

My character is making his own mobile phones, making his own satellite receiver out of a washing basket that’s stuck on top of a ladder. It’s a model, an opportunity to make something in response to my observations and reflections. And it’s wacky, and it doesn’t work.

I’m taking the piss out of myself as much as anyone else. I’ve always had that self-deprecating view. You’ve got to have an upside to a very serious situation.

RS: Your practice is invested in regionally-located creativity. Why is this important?

IT: The story of the regions is a global story told from a regional perspective. It’s an important story to tell. There are times when the regions are forgotten. I’m very supportive of the arts within the regions because there are a lot of people out there doing remarkable stuff.

RS: What will visitors see when they come to your show?

IT: A series of small assemblages that are tools one might need to establish a farm on Mars: communication tools like a satellite receiver; diviners for sourcing water; a series of photographs of me demonstrating and modelling articles you could use on Mars; the videos Objective 1, 2019, and First Post on Mars, 2019. And a sculptural piece, Shrine, 2019, that I tow across the landscape in First Post on Mars. It’s a shrine to celebrate water.

A photograph at the beginning of the exhibition is of my grandfather standing the first fencepost on the family farm in 1949. In celebration of the moment he christened the fencepost from a water bag. That little photograph resonates as a symbol of hope and ambition. It’s like sowing – there couldn’t be anything more hopeful.

We’re falling off a cliff but we’re ever hopeful someone will catch us.

Future Farming: The Mars Project

Ian Tully

Wagga Wagga Art Gallery

18 May–18 August