Frank Lloyd Wright’s suburban dream of Broadacre City is the nightmare within which many of us in the developed Western world now seem to live. The effects of suburban life are prevalent and uncontainable. The corpse of the last half-century of development, the great age of the freeway and the contained detached house, rots away around us.

Perth-born artist Ian Strange investigates some of the symptoms of this process in his practice. His latest exhibition Island is an attempt to highlight the precarity of the home in the post-GFC housing crisis. Wright imagined Broadacre City as a series of isolated lots with single houses on them, reached only by automobile: an island connected by the rivers of the road. It is an idea that resonates with Strange’s own conception of the family and its home as a solitary, precarious and potentially inescapable construct.

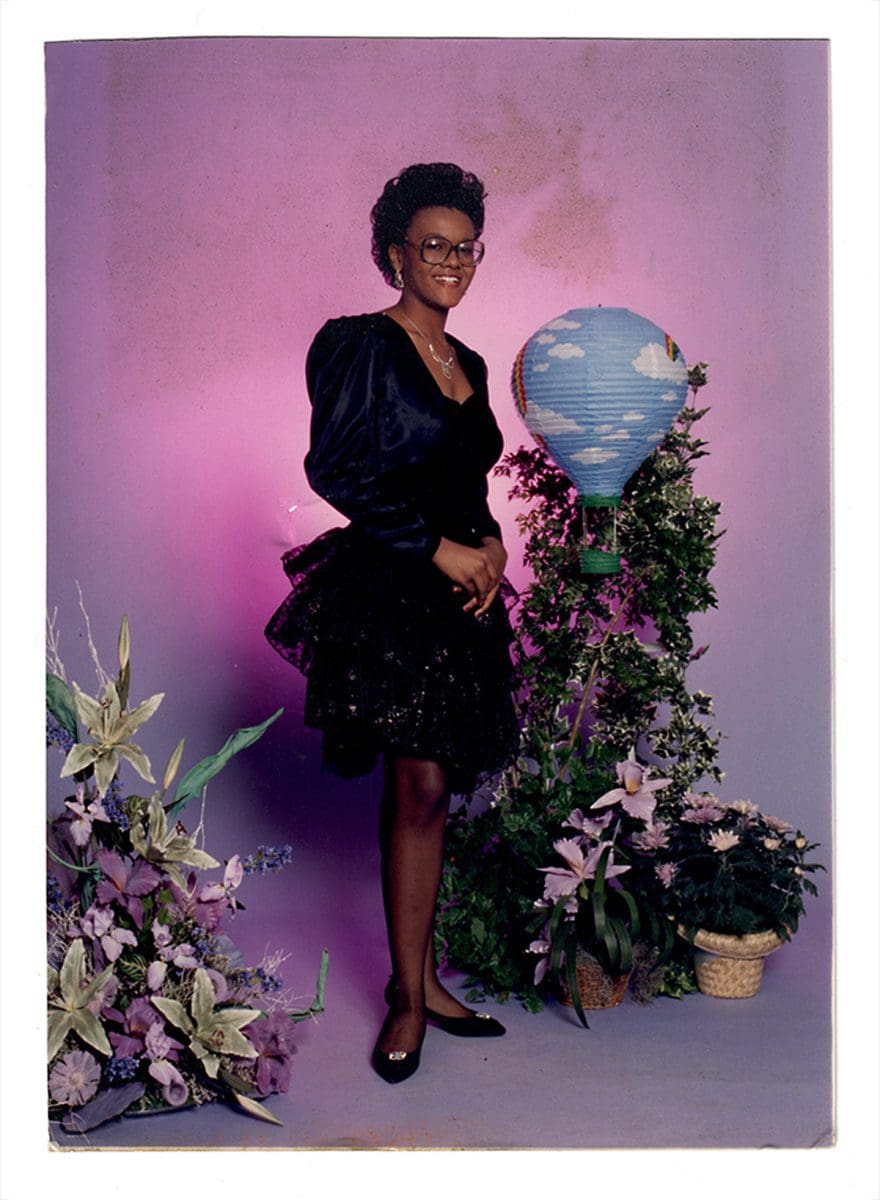

For several years now Ian Strange has been dismembering, destroying, painting and photographing the suburban house in works that resemble the stylistic progeny of Gordon Matta-Clark and Louise Nevelson. His solo show Island continues this trajectory and features a large burnt black skeleton of roof struts, three new photographic works of interventions on foreclosed houses in the American rust belt, and a series of documents relating to the construction of these large-scale architectural works.

In Island, however, text features more prominently than formal interventions. Strange has painted ‘RUN,’ ‘SOS’ and ‘HELP’ in large letters on the facades of family homes.

Strange’s use of text is literal and didactic, quite different from the suggestive text works of Jenny Holzer or Lawrence Weiner. Yet the simplicity and directness of Strange’s messages confers an awkward honesty on the pieces, and amplifies their drama. But the more subtle irony of his interventions (that he has destroyed houses to make his plea, that he is cannibalising the structures he seeks to highlight the vulnerability of) remains something of a contradiction; something that is not yet reconciled within the work.

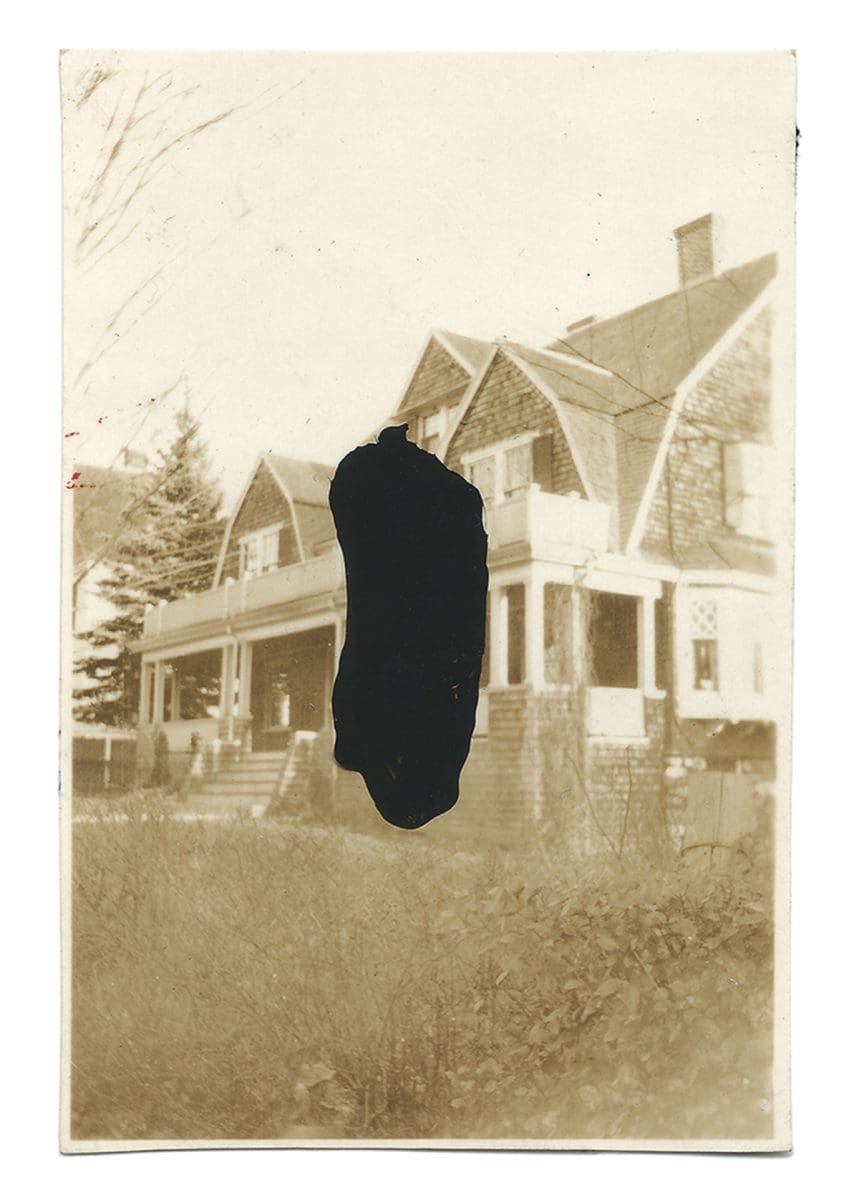

Strange’s work is more comfortably positioned in a cinematic and photographic tradition, like the work of Gregory Crewdson, than within the lineage of conceptual art. His images are extremely arresting. They are large and dramatically lit. Yet the most powerful elements in this exhibition are those that are less often seen: documents of Strange’s process. These include a set of laser printed and collected images in vitrines and a small series of photographs over which ink has been splashed and drawn. These intimate and delicate works provide a link to the artist’s working method, and highlight his more immediate engagement with the image of the house and his re/defacement of it. These smaller works are the most potent elements in the exhibition because of their ambiguity.

In Strange’s twilit work, we witness the fading suburban dream of Broadacre City that was made possible by the automobile and that is dying around us. We are reminded that art, like a parasite that causes the evolution of the host, can work through destruction and devastation.

Island

Ian Strange

Fremantle Arts Centre

22 July – 16 September