Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

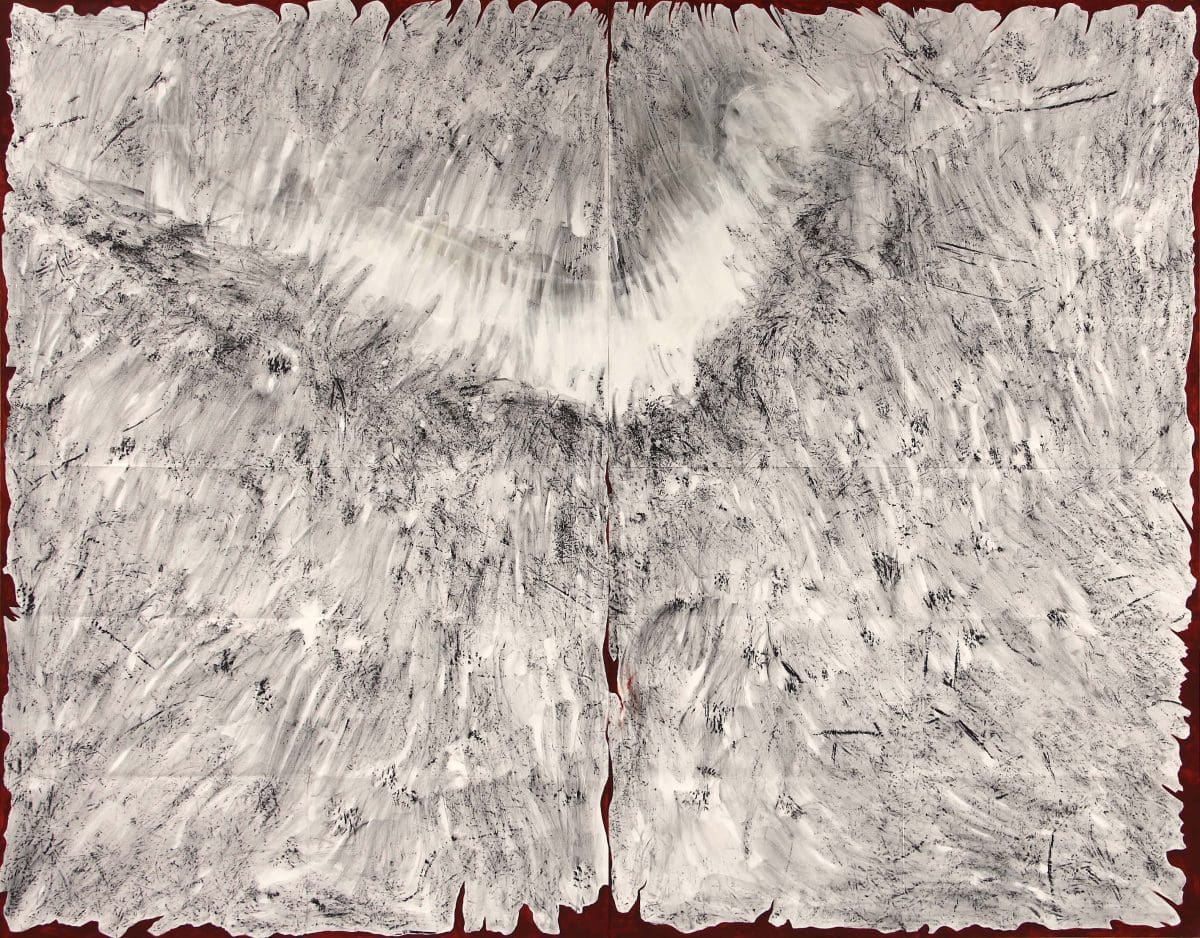

Ian Howard, Hill 60 Trench/Crater, pigmented wax and paint on polyester canvas, 200 x 254cm.

Ian Howard, Hitchen House Coo-ee March memorabilia, framed print, 87 x 62cm.

Ian Howard, A stone, concrete and surprisingly strong mortar house, Bigali, Turkey, pigmented wax and inks on polyester canvas, 200 x 254cm.

Ian Howard, Bigali House Hospitality, (Support work for A stone, concrete and surprisingly strong mortar house), framed digital print, 62 x 87cm.

Like many artists of his generation, Ian Howard was politicised during the Vietnam War. He graduated from art school in the tumultuous year of 1968, when the war was escalating. That war is long over, but the artist’s ongoing practice of investigating conflict zones remains as relevant as ever.

Over the past 50 years, Howard’s work has ranged from life-sized impressions and crayon rubbings of military hardware to mixed-media collage responses to military zones he has visited, from Northern Ireland to Germany and China. But to call his art anti-war is too simplistic, as Steve Dow discovers speaking to Howard while the artist prepares his latest exhibition, Gallipoli to Gilgandra – Coo-ee from the Dardanelles.

Steve Dow: Tell us the story behind the works that comprise this new exhibition.

Ian Howard: I was involved in a workshop about borders and territory on the island of Lesbos last July, which is very close to Turkey. I’d never been to Gallipoli, despite all the work I’ve done over the years in terms of things military. So, we went to the Gallipoli peninsula, but I’d been thinking: how can you do a work on Gallipoli and Anzac Cove? It has been so poured over.

My brother used to be a farmer out in the NSW bush, and from there if you went to Dubbo for supplies, you’d go through the town of Gilgandra, where there was this extraordinary event during World War I called the Coo-ee March. When things were going very bad after the Gallipoli landings, there was a call from the Dardanelles saying, ‘Send more men; we’re in trouble.’

So, en route to Gallipoli, I thought, I know what I’m going to do. The Coo-ee March originated on 10 October 1915, I’m going to see where the Australian troops were on the Gallipoli peninsula in October 1915, and indeed, what were the Turkish doing when the Hitchen brothers hatched this idea?

SD: What do your rubbings and associated photographs for this exhibition consist of?

IH: There are four works. The Australians were at Hill 60, so I’ve done a work from Hill 60. To represent the Turkish recruitment experience, I’ve made a rubbing of a particular house that still exists, that was beside [founder of the Turkish republic] Ataturk’s headquarters, two hours march from Anzac Cove, from which a 20-year-old Turkish recruit left to defend his homeland.

Back in Australia, I headed to Gilgandra, and did a rubbing from the kitchen of the Bill Hitchen house, reflecting on the movements of the brothers on October 9, the night before the march headed off. Finally, I’ve taken a rubbing of the brick remains of the hotel at Balladoran, where the marching men stopped, and the woman who owned the hotel gave each of the 25 volunteers a pound, as recompense for her son being ineligible for service.

SD: You’ve had an ongoing interest in anti-war art since the 1960s, and have travelled to many military zones over the years, haven’t you?

IH: I’m anti-war, as almost every person on the planet is, including most military institutions. If you say I’m an anti-war artist, that’s true, but you too are anti-war, my mother is anti-war, and the chief of the Australian army is anti-war. I’m not anti-military institutions, at all. I recognise their role, and I’m critical of war and actions in war, but I’m not a rabid anti-war artist.

Having said that, the Gallipoli campaign was a disaster. Not only did we lose thousands of young lives, but it had a dramatic negative effect on the utopian ideal of Australia, emerging years earlier in federation. It put class against class. Turkey lost the war and won the peace. Australia lost the peace because we came out of it a destroyed nation.

SD: Of the military zones you’ve been to, what was the most emotionally affecting?

IH: Northern Ireland, because of the sectarian nature of the conflict. The religious component of wars and conflicts I find most disturbing. You can understand war over territory or profit in the broadest sense, whether it’s oil or land, but in terms of religious ideals, that really does seem to be the silliest argument that can be made for conflict: that one person’s image of God is better than yours. It’s so irrational to my mind.

SD: You’re a baby boomer, born in Sydney in 1947. Was there a moment in childhood when you learned about, say, the airplane named Enola Gay dropping the atom bomb on Hiroshima?

IH: The Second World War had a presence during my childhood. There was still the odd gas mask and warden’s helmet laying around in sheds. I remember hearing airplanes of a night as a young kid and hoping it was just a civilian airplane. I knew about the Enola Gay, but it wasn’t something I was particularly interested in.

I came to work with the plane partly through serendipity. Around 1975, I was in Washington DC. I had the keys to the hangars of the National Air and Space Museum. I came across this dusty B-29 bomber, broken up, but all there. I had an American colleague there who dusted it off to reveal the Enola Gay artwork on the nose. I was emotionally moved by it.

SD: You graduated from art school in 1968. Tell me about the politics then?

IH: I was at East Sydney Tech, and 1968 was the end of the modernist trajectory, Minimalism was all-supreme. You weren’t allowed to paint anything representational. Everything had to be pared back; that’s what we were being taught.

Yet, come 5pm or 6pm, the courses would be over, and you’d be in a moratorium down Hyde Park, where the hell and fury of the Vietnam war was raging. I’d come back to art school thinking, ‘What is this about?’

My first show at Watters gallery, 1972, was called Realism – A Return to Subject Matter. The world was such that, if you were going to be an artist, and you were sensitive to the things that effected everybody, including yourself, then you needed to respond.

Gallipoli to Gilgandra – Coo-ee from the Dardanelles

Ian Howard

Watters Gallery

6 – 24 February 2018