Australian artists have long looked to Europe for their influences. Historically trends there have taken time to filter south of the Equator, so we have a long tradition of looking to the past. As ideas get reframed and trends circle around again, it’s worth considering: what relevance do constructivism, communism or revolution have to Australia in 1980? In 1992? In 2017? Quite a lot, as it turns out.

Curated by Chelsea Hopper, the exhibition I Can See Russia From Here brings together a diverse group of Australian artists who have been influenced by Russian art or have engaged with what Hopper terms “the Russian imaginary,” that is, the complex layers of cultural signifiers and values that construct an understanding of Russia, either from within the society or from without.

The line to which the exhibition’s title refers, “I can see Russia from my house”, is widely attributed to 2008 USA Vice-Presidential nominee Sarah Palin. However, it actually came from an Saturday Night Live parody sketch performed by Tina Fey. This slippery footnote (smacking of “fake news”) from a recent election cycle immediately centres the exhibition in the global politics of 2017, viral content, and the scrutiny of Russia-USA relations.

Perhaps it’s for this reason that many of the works feel so contemporary, despite being produced over a span of nearly 40 years. The aesthetic influences of futurism, brutalism and constructivism run through the exhibition; also notions of surveillance and government-think. The latter in particular certainly remain on everyone’s minds.

The aesthetic influences of futurism, brutalism and constructivism run through the exhibition; also notions of surveillance and government-think.

A pair of strikingly beautiful untitled watercolour drawings from 1992 represent a collaboration between Eugene Carchesio and the late luminary Gordon Bennett. Each artist worked on half of the paper, producing gem-like geometric abstractions in the constructivist style. One constructivist in early 1990s Brisbane seems like a weird anomaly; two of them together are an intriguing conversation.

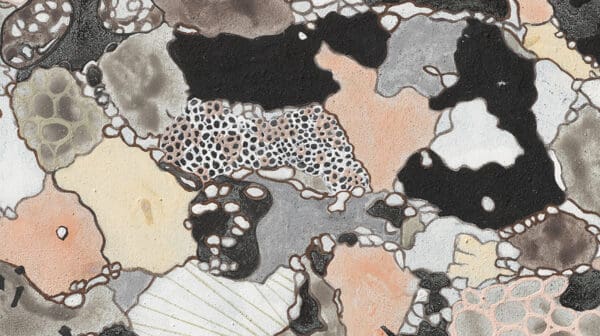

Hung side by side, John Nixon’s Black and Brown Cross and Eugene Carchesio’s Cosmos both refer to the legacy of Malevich’s Black Square, first painted in 1915 (he made several versions) and often called the “zero point” of painting. Nixon’s work was made in 1988, Carchesio’s in 2006; the zero point of painting comes round again and again, each time new. Carchesio’s delicate black paper cones, repeated across the surface, collapse the infinity of the universe into a geometric precision.

I looked for a long time at Meg Stoios’s work Next Stop, 2017: a small square photograph of a headphone-wearing man reading the Communist Manifesto on a crowded Melbourne bus. Presented as if taken surreptitiously on a smartphone, it’s a striking conflation of the notion of surveillance within the square frame of Instagram.

One of the richest works is Jemima Wyman’s Propaganda Textiles Swatch Book, 2017. It draws on Soviet propaganda textiles of the 1920s and 30s: repetitive patterns of tractors, machinery, or other symbols of harmonious State-sanctioned production. Wyman’s swatches are digitally printed, her abstract patterns multiplied over the image of a masked protestor. Sourced online and representing dozens of rallies worldwide over the last six years, they range from Yemen to London to India, from abortion rights to government overthrow, from balaclavas to Scream masks. It’s a complex and visceral response to contemporary grassroots politics, turning our empathy fatigue into a swatch full of tactile possibility.

Stuart Ringholt’s Wrist Watch (19 hour), 2004, looks like an ordinary analogue man’s watch, attached to the wall. On closer inspection, however, it presents a 19-hour cycle: the possibility of so much more time (and what to fill it with) is a glorious one. It also touches on the compression and expansion of time and geography visible within the exhibition.

The final work of the show (although the first encountered, as it’s in the middle of the gallery) is Alex Hobba’s The Future Began on the Ruins, 2017, an inkjet-printed textile that lies half-crumpled across the floor. Providing a literal space for the future to begin, it’s a hopeful ending, I think, to this ambitious and wide-ranging show.

I Can See Russia From Here

Curated by Chelsea Hopper

TCB inc.

7 June – 24 June 2017