Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

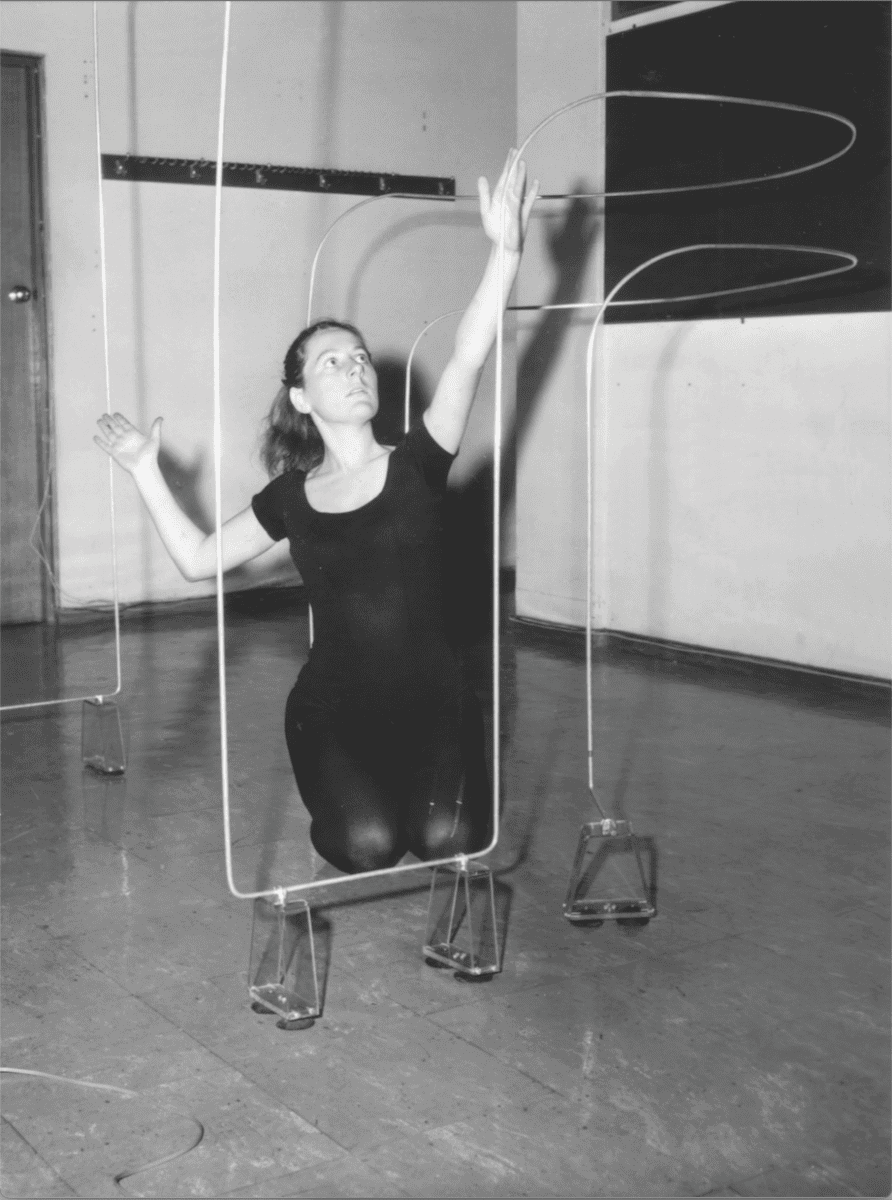

Philippa Cullen on a pedestal antenna rehearsing Homage to Theremin II at the Joseph Post Auditorium, NSW Conservatorium of Music,1972. Photo Lillian Kristall. Courtesy of the Estate of Philippa Cullen.

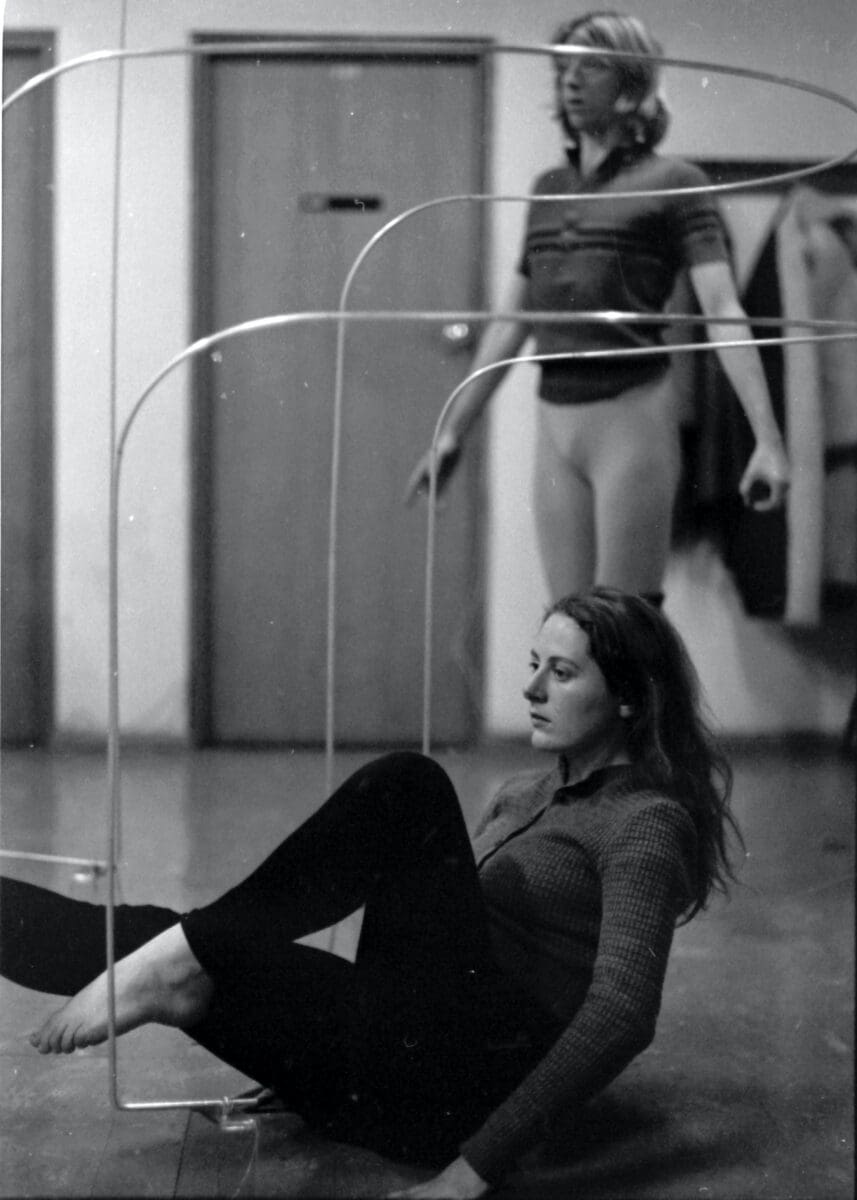

Philippa Cullen with the wire loop antennae developed by Manuel Nobleza. Photo Alex Ozolins. Courtesy of the Estate of Philippa Cullen.

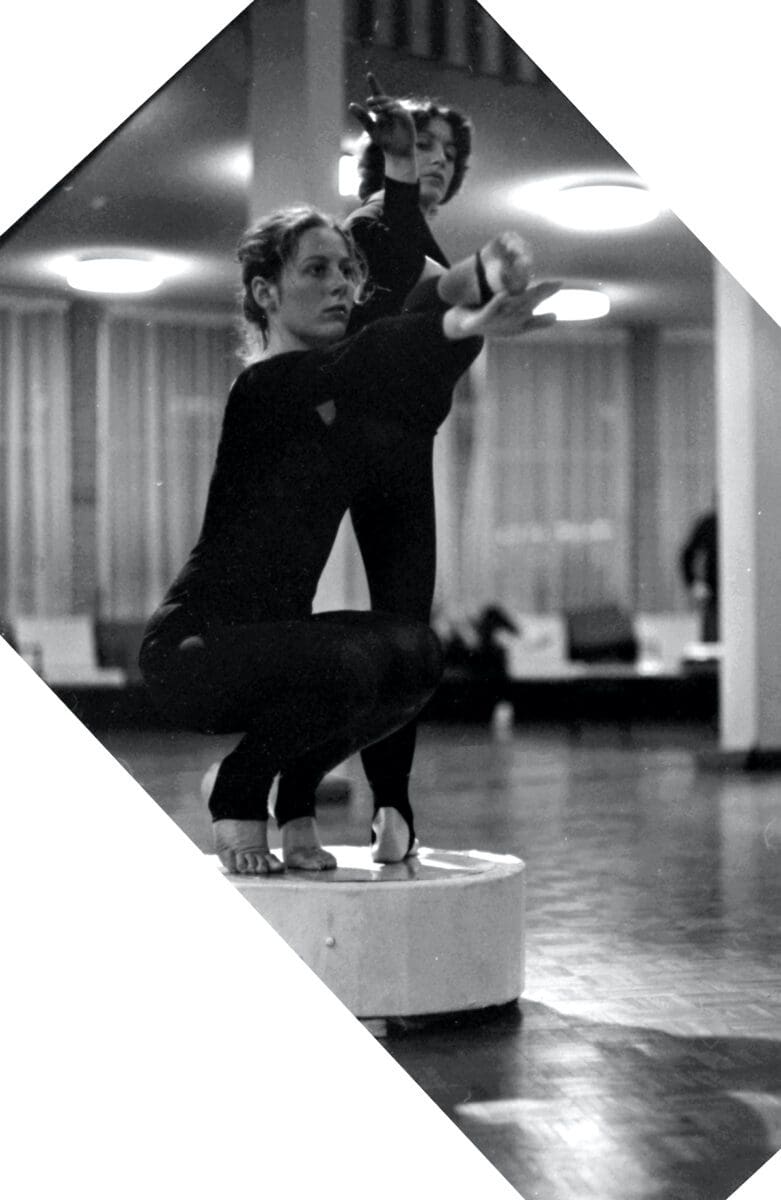

Philippa Cullen and Jacqui Carroll working together on a pedestal theremin antenna in a rehearsal for Homage to Theremin II at International House, Sydney University, 1972. Photo Lillian Kristall. Courtesy of the Estate of Philippa Cullen.

Philippa Cullen and Peter Dickson working with the theremin antennae in a rehearsal for Homage to Theremin II, 1972. Photo Lillian Kristall. Courtesy of the Estate of Philippa Cullen.

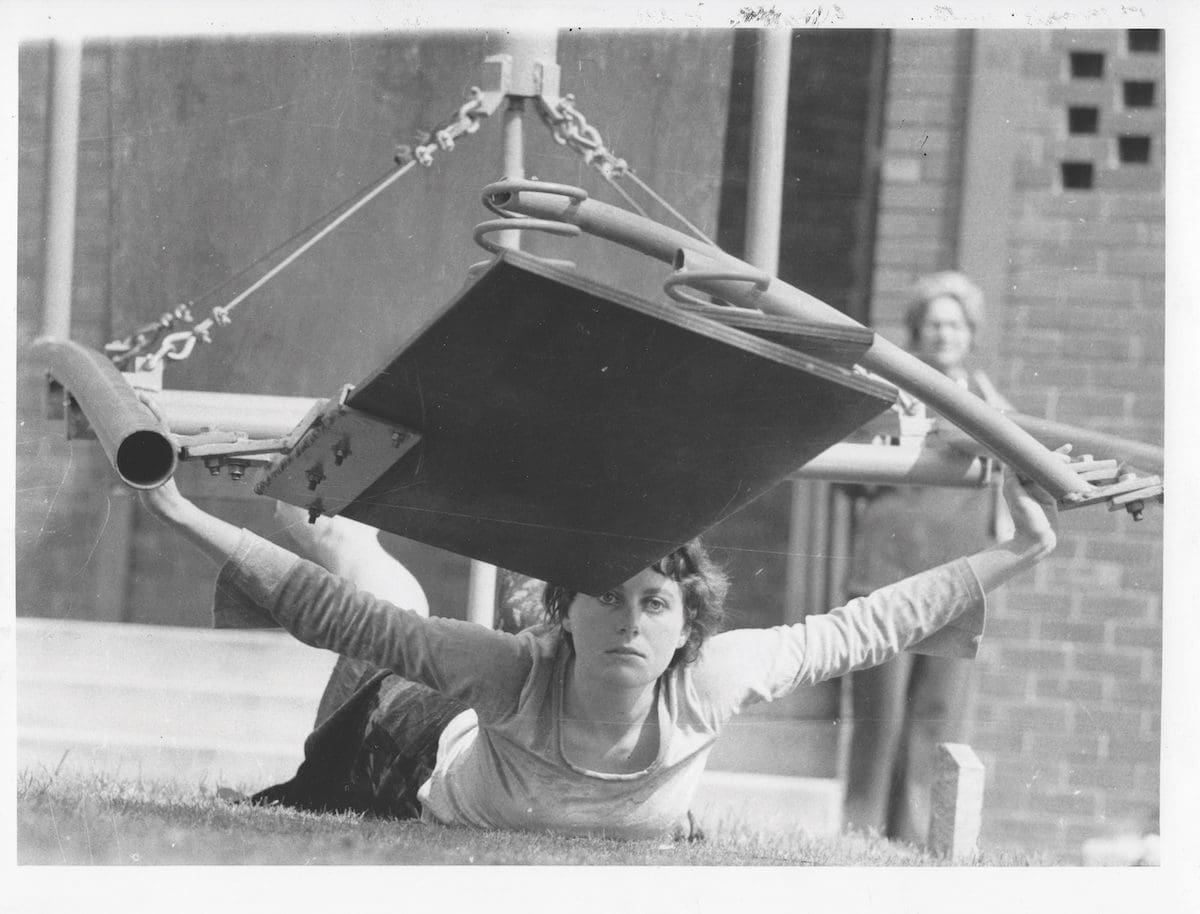

Philippa Cullen with Marr Grounds’ sculpture Berkeley Revisited (1974), Mildura Sculpture Triennial, 1975. Courtesy Evelyn Juers, Garamond Publishers, and the Estate of Philippa Cullen. Photo Don Turvey.

Dance and music are complementary, almost universally linked in the human world. It is rhythm that stimulates movement; it is instinct. I’m picturing my son at nine months old, utterly enraptured by the electronic sounds of Aphex Twin, bobbing to the beat on all fours. It is music that leads our bodies toward dance; a dancer moves in time with a composition that they seldom make themselves. Yet Philippa Cullen (1950-1975) wanted to free the dancer from this contract so they could create their own music. Her quest was to tune into and elucidate the sound of dance, so movement could lead, rather than follow the music.

Dancing the music: Philippa Cullen 1950-1975, showing at McClelland Sculpture Park + Gallery, celebrates the life and legacy of Cullen as a dancer, choreographer and experimental artist. Cullen died young and suddenly, at the age of 25 from surgery complications, but has left lasting impressions on dance and experimental electronic music in Australia and internationally.

A professionally trained dancer with a humanities degree, Cullen travelled the world, searching for ways to seduce sound from dance. She spent time in Africa, exploring the role of dance as a cultural ritual for communities. She met with contemporaries in the United States and Europe throughout the early 70s, and built upon works by John Cage and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. For Cullen, dance, as she explained, was “an act of rejoicing, more than a tool of communication”. In 1975, curator Kiffy Rubbo wrote, “It is almost impossible to describe the special quality of Philippa’s dance—her ability to communicate and to liberate the energy and beauty of the body . . . her stillness and energy . . . her singular spirit.”

Dancing the music curator, Stephen Jones, worked closely with Cullen in the 70s. After she passed away, he was handed a box of her belongings— a personal archive which is now included in the show. Original documents, photographs, and video footage are also displayed, alongside some of the interactive technologies Cullen explored.

Through Cullen’s archive, Jones hopes to inspire audiences with new ways of thinking about sound. Perhaps by tuning into the subtleties of sound, it will help guide us toward new practices of listening to ourselves and others. He explains, “For Cullen the intention was to place the dancer inside the musical performance in a similar way to the musician. The action of making sounds is always, in some sense, a matter of working within a system, be it a system of strings and sounding boards, or a system of electronics leading to a speaker-box. In working inside the process, the gestures of the musician are movements as much as, in a larger scale, the motions and gestures of dance.”

We don’t often think of the 70s as a period of great technological innovation, and by today’s standards the electronics of that time are now charmingly, impossibly retro. But major steps were taken in information and communication during this time—the first floppy disks, mobile phones and digital cameras—and Cullen was fascinated by technology. She experimented with computational compositions, electronic instruments and synthesisers, and was enchanted by the theremin, a musical instrument played without physical contact by interacting with electromagnetic fields around its two antennae. Cullen would customise the instrument’s antennae so that a dancer’s body could transform movement into sound.

Jones recalls that for Cullen, “Any new technologies that could be accessed were to be explored, from the theremins and other body-scale sensors that could be used interactively, to sound synthesisers and computers, to biofeedback and video.” The haunting, otherworldly sounds of the theremin became, for Cullen, the first sounds produced by dance. She expanded the theremin’s potential beyond electromagnetic fields with the use of a synthesiser, and later developed pressure sensitive floors that detected a dancer’s movement.

This led to Cullen creating interactive sculptural forms that became choreographic landscapes, constructed for bodies to negotiate through and around. Envisage large, curved metal antennae throughout the space, interactive round pedestals, black electrical cords marking the ground, and triangular pressure-sensitive floors. For Cullen, the movement of bodies would awaken these inanimate frameworks.

Cullen had an infectious charm and magnetism, collaborating with composers, musicians, dancers, artists, technicians, engineers, actors and more. She secured grants to build new technologies that would inhabit the stage with her dancers. During one performance when her computer system and theremin failed, a team of computer scientists, whom she had only just met, worked through the night to write new software for a reinvented performance rescheduled for the following day.

Jones reflects, “She had a period of roughly six extraordinary years during which she developed, with the support of a diverse group of musicians, dancers and electronics engineers, perhaps the most technically sophisticated interactive systems of the period, many of which have not been surpassed since.”

Cullen was a pioneer at the interface between dance and experimental music, and her work continues to inspire artists and performers today. Her vision of “a new medium in which dance is inseparable with technology, music and lighting” is closer than ever.

Dancing the music: Philippa Cullen 1950 – 1975

McClelland Sculpture Park + Gallery

Until July 17

This article was originally published in the May/June 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.