Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Honor Freeman, Shape of tears (detail), 2019, porcelain, 1 m x 1 m; Courtesy the artist and Sabbia Gallery, Sydney.

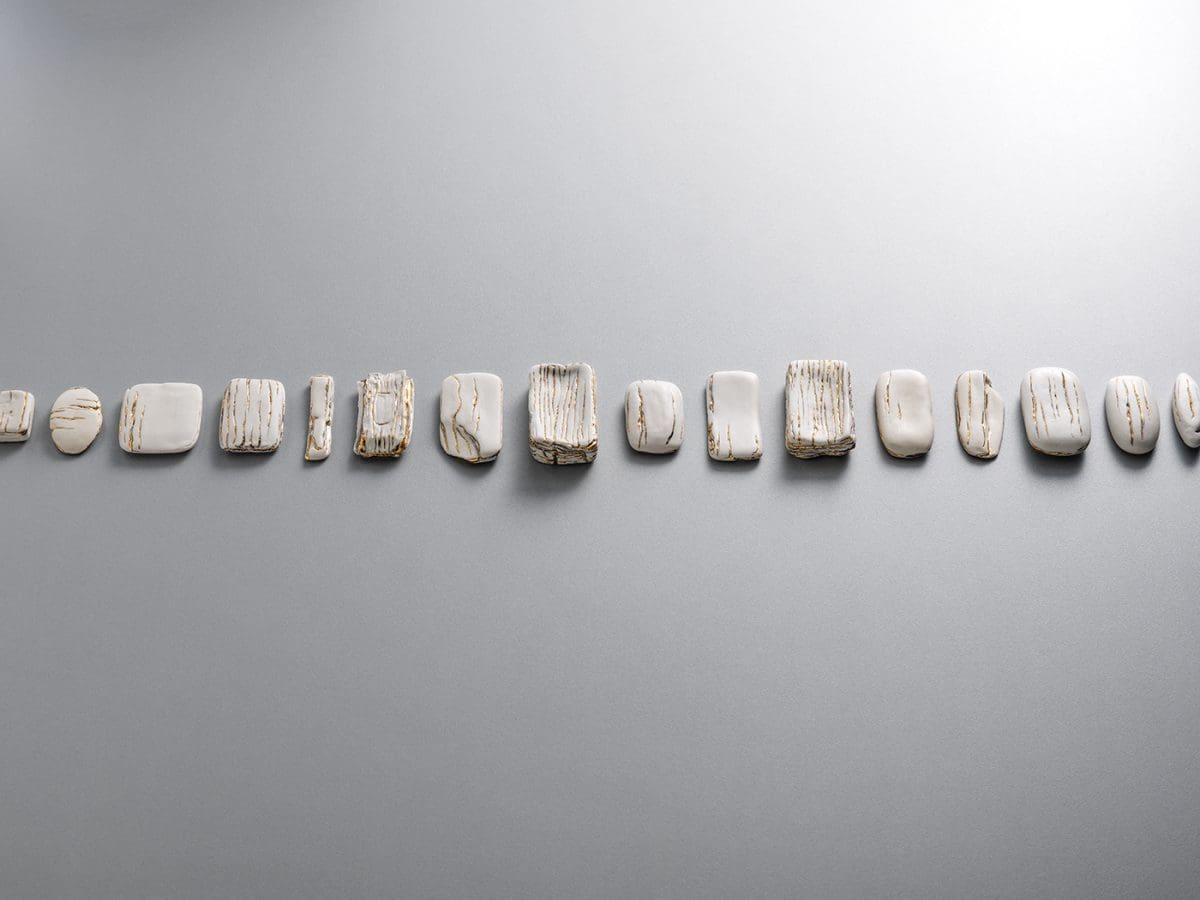

Honor Freeman, All the tears I cried (detail), 2019, slipcast porcelain, variable dimensions; Courtesy the artist and Sabbia Gallery, Sydney.

Honor Freeman, Shape of remembering, 2019, slipcast porcelain, gold leaf, 3.5 x 33 x 29 cm; Courtesy the artist and Sabbia Gallery, Sydney.

Honor Freeman, Things I know you’ve touched (detail), 2019, slipcast porcelain, gold lustre, variable dimensions; Courtesy the artist and Sabbia Gallery, Sydney.

Honor Freeman’s Ghost Objects exhibition is the culmination of a year-long artist in residency at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) in conjunction with the Guildhouse Collections Project. Zoe Freney spoke to Freeman about her interest in everyday objects of mourning and loss, the ability of clay to hold memories, and her use of the brittle poetry of ceramics to create vessels that hold time, space, legends and tears.

Zoe Freney: Ghost Objects is part of the South Australian Living Artists Festival 2019. What is SALA’s importance in South Australia and what does it mean to you personally?

Honor Freeman: Working as I do in relative solitude through periods of intense concentration, SALA is all about reconnecting with friends, colleagues and the wider visual arts community at events and exhibition openings. It is really important that local artists and makers are celebrated.

There is a democracy to SALA too – it welcomes and includes well established and greatly admired local artists as well as people just starting out. SALA can and does hold all of that.

ZF: The Collections Project invites artists to interact and collaborate with objects in the collection of AGSA. With your interest in small moments and the everyday, what drew you to this project?

HF: When I was invited by AGSA to take part in the project I was initially daunted. I was familiar with works from the Gallery’s permanent collection on regular display, but of course that is only a fraction of what they hold. I was interested in the liveliness of works that are rarely seen by the public.

It was a privilege to be able to touch and hold very old, sometimes ancient objects. Holding the handle of a Roman pot, for example, it almost seemed to vibrate. I could imagine its story.

I was thinking about the way objects hold their own stories, the stories of those who made and used them. I feel like it is a big responsibility to hold these vessels, to value them and interpret them for people to see them again and in different ways.

ZF: What was your process in selecting particular objects and artworks to respond to?

HF: I wanted to create dialogues from different angles and to interrogate different aspects of the collection because things have been collected and curated for so long from a particular viewpoint.

I was influenced by the work of Matt Smith, who was the ceramics resident in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London a few years ago. He looked at how an outsider perspective, like an LGBT viewpoint, can reframe a museum’s collection and edit narratives of power.

I was drawn to the quiet corners and to things that seemed to have stories to tell, simple, mythical, debunked and imagined.

ZF: Why was it important to you to draw attention to artefacts of mourning and solace within AGSA’s collection?

HF: My practice has long been an exploration of the language of everyday things and their power to symbolise meaning in our lives. I give them value through the mimetic potential of ceramics.

A keystone object for me was a tiny Roman glass flask, called a lachrymatory. For a long time it was thought that these vessels, found in great numbers in Roman, Greek and Hebrew tombs, were used to collect and store the tears of mourners.

This beautiful story has in more recent times been debunked by science, but it got me thinking about tears, and my own experiences of loss and sadness. It seems now our rituals around death are practiced with restraint. I have always made sense of things through making and so that’s perhaps what I’m exploring in this project – making sense of grief through making.

ZF: Tell me something about the materiality of porcelain and how your processes add meaning to the items you selected to work with.

HF: Ceramics will always teach you. It is not for the fainthearted. Working with porcelain can be masochistic and heart-breaking. Inspired by the Roman lachrymatory I set out to make buckets for tears.

Do you know the average human will cry 61.5 buckets of tears in a lifetime? The first bucket I made was a perfect thing, but I opened the kiln to cracking and disaster for some months following. I have made a graveyard of failed buckets for tears.

Clay has always been present in rituals of grief, death and mourning. Ceramic is fragile, but its fired permanence has endured over centuries and supplied much of what we know and understand about the past.

There is a small Chinese pot in the AGSA collection, and you can see where the potter held it as it was dipped in the glaze, you can hold it with your finger and thumb the way he or she held it, and in between are hundreds of years. Clay is full of meaning, and is a material with memory.

ZF: The way your work immortalises ephemeral human products and emotions like tears and grief is very poignant…

HF: Throughout history humans have given objects lives and imbued them with meaning. Mourning jewellery often includes pearls, which symbolize tears. I have been using an on-glaze lustre for some of this work, on ceramic handkerchiefs, and the surface of the buckets, and the effect is reminiscent of mother-of-pearl.

Vessels can hold memory physically and metaphorically. AGSA has recently acquired a beautiful Japanese tea bowl called Morning Light, bearing the traditional gold vein lacquer repair of kintsugi, simultaneously holding the tension of frailty and resilience – a re-birth of sorts. In interpreting the AGSA’s collection in this way perhaps I have processed and made sense of my own grief.

Ghost Objects

Honor Freeman

Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA)

27 July – 29 September