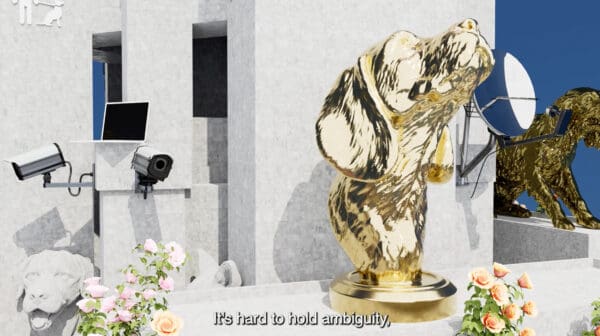

Sophie Penkethman-Young’s Scroll Play

Sophie Penkethman-Young dives into the cursed, chaotic and charming depths of the online world to create inquisitive artworks exploring technology, the internet and capitalism with humour.

I can’t think of a contemporary artist who skewers the art world’s class anxieties as wittily as Sarah Lucas. The sculptor, who represented England in the 2015 Venice Biennale, grew up on an East London council estate, the daughter of a milkman and a sometimes cleaner. Over a series of mornings in 1992, she placed two freshly fried eggs and a kebab on a kitchen table in an empty storefront. The work, Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab, became a bawdy riff on the female anatomy. But it also made working class signifiers—the no-nonsense British fry up, the cheery East End kebab shop—the stuff of high art, exposing the arbitrary nature of our class biases in the process.

Lucas came of age in a post-Thatcher England, riven by aristocratic privilege and centuries of deep class division. But the questions her work asks—who gets to make art? who gets to consume art?—can apply equally to Australia today. As the evidence shows, we’re a nation enveloped in class divisions. Recent research by the International Monetary Fund found that Australia was ranked fourth in the developed world when it comes to the wealth gap between its richest and poorest regions.

A 2017 Australian National University report revealed that we could divide the country into six social classes—from the ‘established affluent’ to the ‘precariat.’ Analysis from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development discovered that if you’re born into poverty in Australia, it can take four generations for your descendants to earn the average wage.

We like to pretend that we’re the land of the fair go, a country where your station in life is dictated not by accidents of birth but the accumulation of talent, hard work and effort. To speak of class in Australia is to violate a secret code, one that determines our selfimage. And to speak of class in the art world, where economic, social and cultural capital is a precondition of membership, is to cast this code in neon. It’s to hold it up to the light.

Of course, art has always had a tangled relationship with class—artists historically and today have often created works through a classist patronage system. Think of Michelangelo, bankrolled by the Medicis; American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and his blue-blooded lover Sam Wagstaff; or Heide’s John and Sunday Reed, whose family fortune nurtured artists like Albert Tucker and Moya Dyring.

The problem, I think, isn’t that the art world is powered by wealth but that it pretends that class isn’t a barrier to entry and that our material realities are all the same.

Making Art Work, a 2017 report from the Australia Council, found that Australian artists earn an average of $18,800 a year from their creative work. This state of low earnings is exacerbated by a culture of free labour and unpaid internships. For this we can partially thank the myth of the starving artist, the notion that art is a labour of love—not money—that should have ended with 19th century Montmartre but still has an insidious hold over the way we compensate creative workers for their time and talent.

In the short term, this prevents the opportunity for artists to earn a living wage ($41,184 a year according to April 2019 data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics). In the long term, this can shut down prospects of class mobility: of who has the monetary security, and therefore the freedom, to create art. The choice, for working-class artists, is often between a career in the arts or the chance to become financially stable.

These stakes are only heightened by a spate of continuous funding cuts. According to a 2016 Guardian report, grants for individual artists and writers are down nearly 70 percent since the Australia Council lost $105 million in funding under Senator George Brandis. By November 2019, a quarter of small arts organisations found themselves without Australia Council backing, and then, in December 2019, Prime Minister Scott Morrison amalgamated the Department of Communications and the Arts into the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, symbolically erasing the word ‘arts’ from the national agenda. The move crystallised the notion that art is less the glue that binds society together than it is a silent luxury only accessible to those whose status never depended on the protections language can afford.

Staying relevant in the art world has also meant attending previews mid-week, swinging by exhibitions on the weekend, maintaining art world knowledge and nurturing a network of relationships. The theorist Pierre Bourdieu famously referred to this as ‘habitus’—the physical embodiment of cultural capital that determines our tastes and is subject to its own rules. And so many of the art world’s defining rituals presume a level of class privilege too.

Your ability to be part of this habitus assumes that you have few pressing demands on your time, the luxury of blurring work and leisure. In a December 2014 article in the Canadian publication Momus, Andrew Berardini writes about how his career in the art world has made him part of the ‘poverty jetset’— the network of artists, writers and advisers who fly between international openings and biennales, an inversely proportional relationship between the high glamour of his life and the low state of his bank balance. I was once on a panel with a well-respected curator whose status as a single mother made Thursday night openings impossible.

All of this is made worse by Instagram, which flattens class differences, drawing false equivalences between artists, writers, curators and the high-worth collectors who share the same orbit. In the art world, class isn’t so much a barrier but an organising principle, the force that dictates who gets to belong—and who’s left out.

The art world should hold a mirror up to the real world. It should capture the breadth and depth of experiences. But by treating class as if it doesn’t matter, we shut down new voices. By pretending that material realities aren’t important, we ignore the limits of artists’ lives. Close your eyes and picture culture without Sarah Lucas’ fried eggs and kebabs, or Grayson Perry’s tapestries and sculptures that expose our taste prejudices, or any number of artists who contest the arbitrary nature of our class biases. If great art helps us see the world anew, our classist lens is holding us back—and the act of looking is a lot less interesting for it.