Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

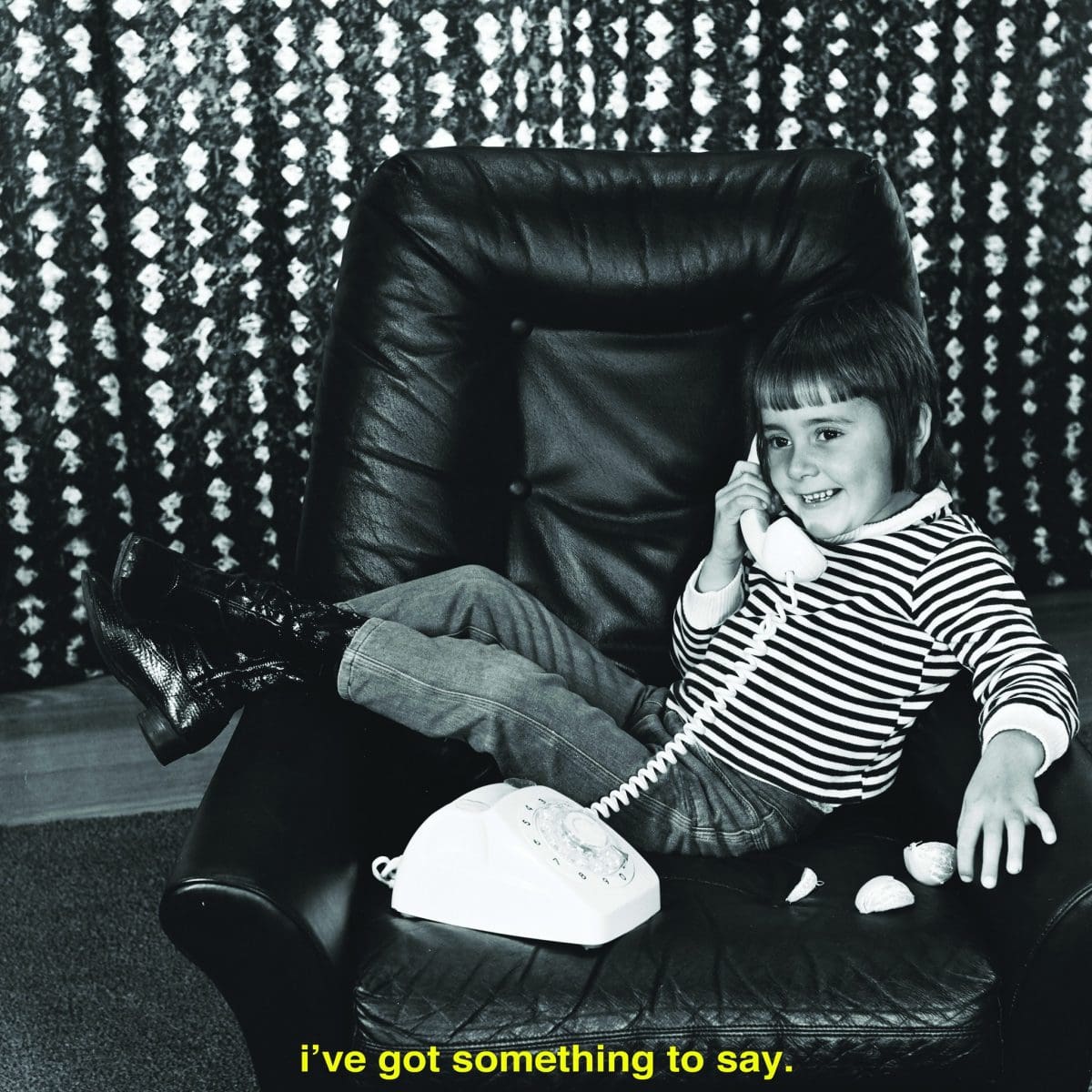

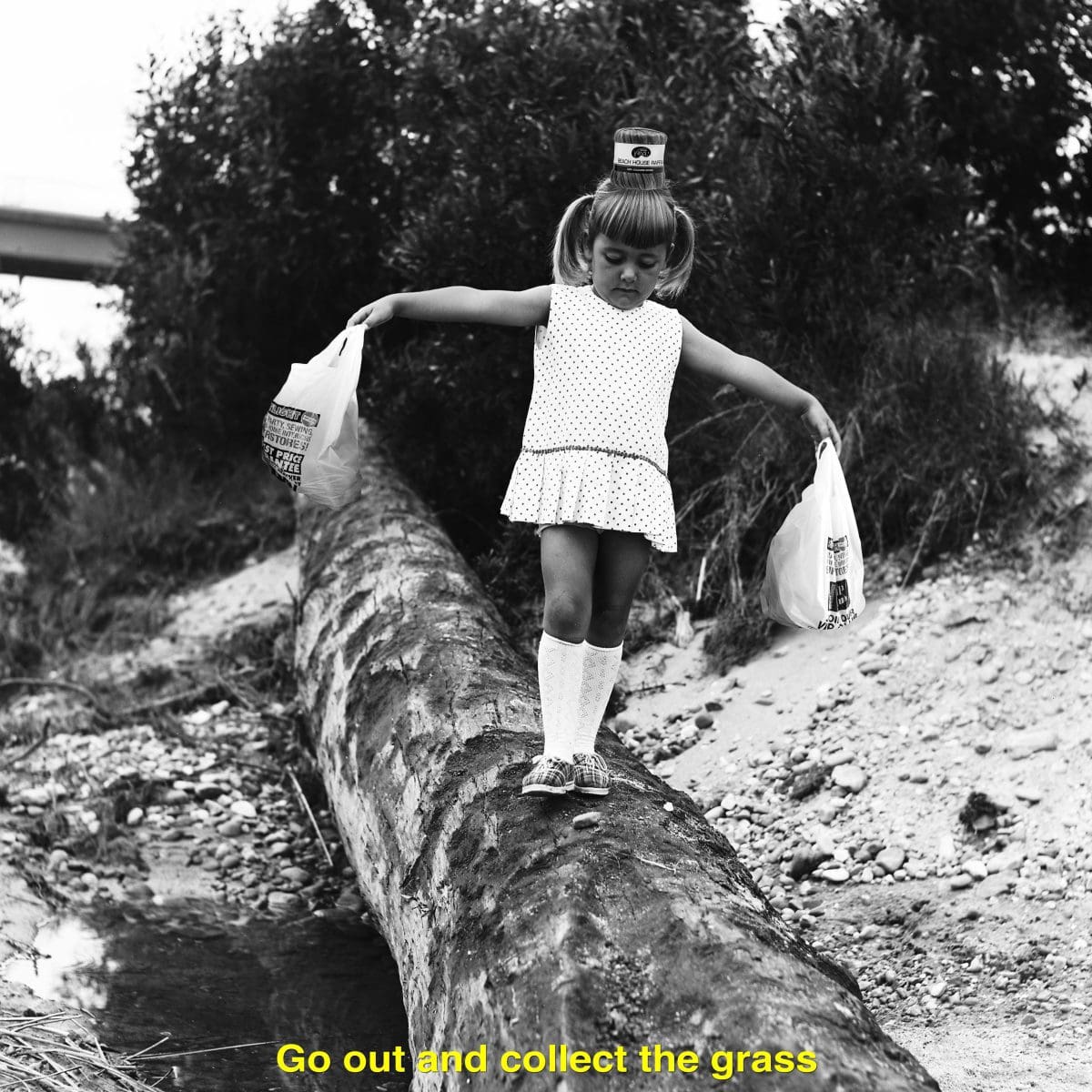

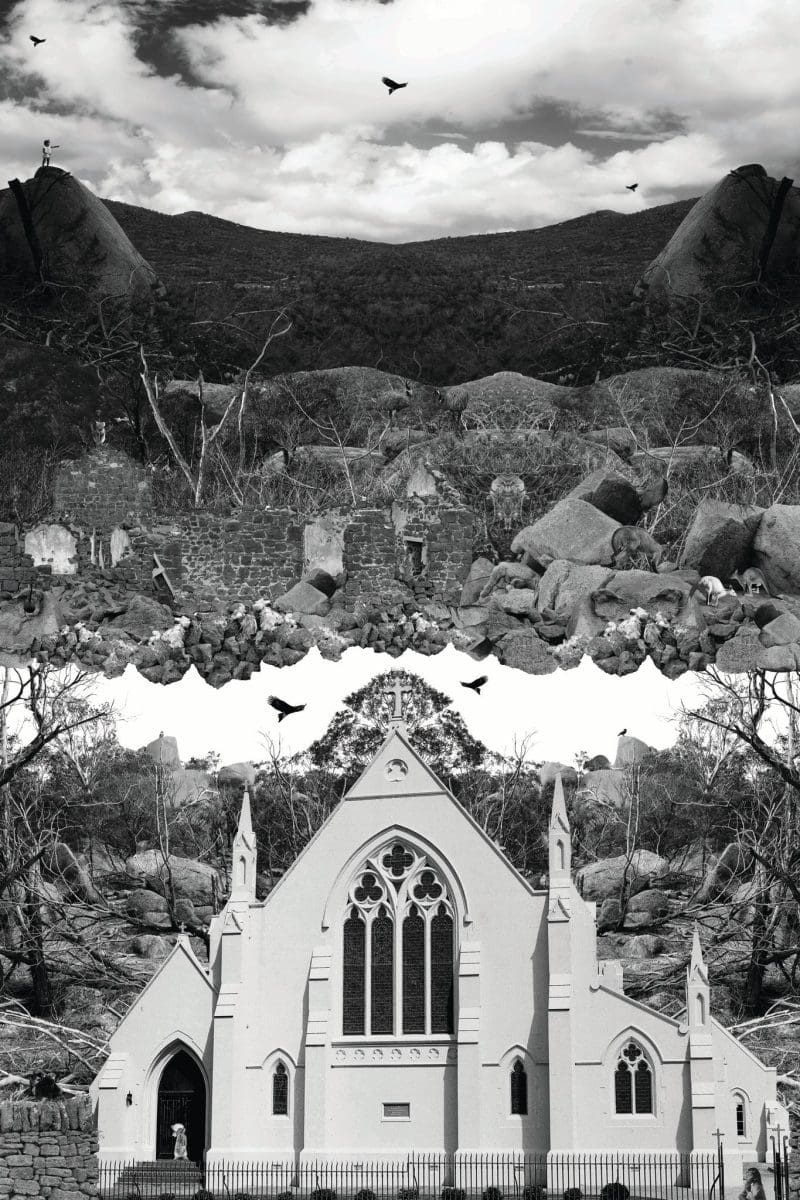

Between 2016 and 2019, Gunditjmara artist Hayley Millar Baker created five photographic series in black-and-white. Appropriating and citing images and research from history, alongside digital editing to create layered assemblages, Millar Baker’s images speak to Aboriginal experiences and build a complex conversation on time, memory and identity. These exquisite images were shown in a 2022 survey exhibition at Flinders University Museum of Art titled There we were all in one place. We asked Millar Baker 20 quick questions about the exhibition and her art experiences.

Describe your practice in seven words?

Auto-fiction, multifaceted—conceptually and visually, retrospective, currently shifting!

Your first art love?

Paul Gauguin and Lin Onus.

Why do you shoot mostly monochromatic works rather than colour?

I actually shoot in colour and colour grade to a monochromatic palette. In saying that though, the images I have used from my grandfather’s photographic archive in my previous work, I’m the Captain Now, 2016, and Cook Book, 2017-2019, are shot in black-and-white.

I think there is a romantic quality to black and white photography and film. It’s nostalgic; it suggests robust narratives that require investigation through connection to film noir. It purposefully eludes any particular era, but suggests the past, memory and history—any time that isn’t right now. And I find that desaturating an image removes any extra distractions that could potentially take the eye away from finding or following the quietly placed storyline markers.

Best advice you’ve been given about making art?

I am the artist—I call the shots.

Why do you think you gravitated towards photography to explore Aboriginal experiences, identity, culture, and memory?

It was a no brainer for me. I trained and practiced in painting for many years but when my late grandfather’s photographs suddenly came into my possession in 2016, I knew I needed to use them to revision our (collective South-East Aboriginal) stories, and give permanent voice to our departed once-voiceless ancestors. I got a little bit of my family history written (collected) into ‘history’, and those stories will now be cared for and managed by those institutions.

If you could collaborate with any artist, dead or alive, who would it be?

I’ve been thinking about this question all week. There are just so many people for so many different reasons. If I had to ‘go big or go home’, I reckon Shirin Neshat for her film work, and Tracey Moffatt for her photographic work.

Quick advice for young artists?

Position yourself and take your time.

Best time of day to create?

Definitely all day every day, but my best ideas and developments come to me at unreasonable hours of the night when I should totally be asleep—but instead I’m thinking about art, of course!

What would a typical working day look like for you?

A lot has changed for my typical working day over the past couple of years. For one I added another child in 2020 to our little family—two young kids and an extended pandemic lockdown changes quite a lot for someone’s art practice! A typical working day for me looks like an early start, lots of meetings, some procrastination, and a smidge of progress on my projects (I’d like a bit more than a smidge, but progress is progress!). My projects tend to be big and require a fair amount of time for development, so I like to take that time.

Do you think about the viewer when creating and how they may receive or experience your work?

The viewer’s experience of the work had previously been a big influence on the way I made my work. I’m very conscious of how long someone looks at a piece of art or positions themselves as either relating or not relating to art. Previously I was making very heavy and historically loaded works so it was important to me how viewers would connect and experience an understanding.

But now that I am centering semi-autobiographical and auto-fiction narratives, I’m less concerned with the audience’s reading of the work and more interested in the experience of the work, which comes down to the install to be experienced in its optimum state. Because in reality, once the work is out in the world, my job is done.

The first photograph you ever took?

I had so many disposable cameras as a kid. My first photograph could have been a wonky photo of my childhood dog Conan (RIP).

What is it about photography as a medium that you enjoy?

In the simplest way: I enjoy its flexibility of bending realities and truths while it still remains credible as ‘documentation’.

Photographers who’ve influenced your work?

I’m inspired by an artist’s mind, the way they navigate and communicate their ideas and concepts. I’d have to say I’m inspired by mostly painters and filmmakers/ films. I work in an abstract way with photography so I like to get lost in the minds and ideas of artists who create their works in more abstract or symbolic readings. That said, the minds of many photographers have inspired different ways of thinking throughout different stages of my practice but most recently I’ve been enthused by the work of Hannah Wilke and Julie Rrap.

An art experience that’s stuck with you?

Ask me in December when I return from my three month residency in Prato, Italy! For now, I’ll shout out to Amrita Hepi for her work Dance Rites that was exhibited in the 2017 Tarnanthi at ACE Open. Viewing that work for the first time knocked the next domino in my mind. The previous domino was knocked by artist Hannah Wilke in 2008.

Classic ‘Hayley Millar Baker’ drink order at the bar?

I only drink once in a blue moon, but I’d love a Piña Colada.

What camera do you use?

So many! Lately and for upcoming projects I’ll alternate between my Fuji GFX and Mamiya RB67. Nothing compares to the monster that is the RB67!

For the recent exhibition Ceremony at the National Gallery of Australia (and showing at UQ Art Museum) you showed your first film work. How did shifting from photography to film feel?

It felt great and like it was a logical medium to explore more complex themes in a delicate and minimalist way. And I have to say I love puzzles—and filmmaking is the ultimate puzzle! So many ways to shape a project, and luckily I had an incredible team to reign me in and be by my side to bounce off.

Beauty or politics?

Both.

Is there a link between art and cultural change for you? How do you see that relationship?

Of course, because art generates dialogue, empathy, investigation, reflection, relationships, and ideas that directly influence human behaviour—maybe not right away, but art stays with you and develops quietly over time.

Your survey show There we were all in one place is currently touring Australia. What can we expect to see?

You can expect to see all five photographic bodies of work from 2016 to 2019—all together! Having all the works together—I’m the Captain Now, 2016; Toongkateeyt, 2017; Cook Book, 2017–2019; A Series of Unwarranted Events, 2018; and The trees have no tongues, 2019—marks a deeply retrospective exhibition for me. Now having pivoted in my practice, having this tour acknowledges that first chapter in my professional art practice.

Nyctinasty

Hayley Millar Baker

Chau Chak Wing Museum

On now – 11 February 2024

This article was originally published in the July/August 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.