Editor’s note: This year has represented a tipping point in the relationship between artificial intelligence and creative labour. But despite the fact that AI may be worsening the historical precarity facing artists, the conversation, to me, has failed to address the social and emotional consequences for creative workers. Or how they are reframing their vocation in the process.

In the second essay in Art Guide Australia’s The Long View series, the acclaimed feature writer Stephanie Wood draws on her own perspective—and those of visual artists—to investigate the forces that define this moment. She also asks if the power of art to forge connection will survive this new landscape—and endure.

—Neha Kale, Editor-at-large

In a world in which the new wave of AI is reframing our relationship with creative labour, how do artists negotiate an impending crisis of relevance and understand the true value of their work? Stephanie Wood reports.

For a while now and with increasing frequency, a spectre has trespassed on my thoughts: lamplit, in bonnet and apron, she hunches over her work, making lace. She is not easily evicted, nor is the unsettling story she tells. “Nothing lasts forever”, she says, “my story is yours too.” Close to a decade ago I chose to take a redundancy package from The Sydney Morning Herald where I was a features writer. I knew that leaving the protective shield of my staff role and striking out on my own would not be an easy road. For two decades, the digital revolution has pummeled the business models supporting the publishing industry and the creative workers who rely upon it for a living—writers, journalists, authors, editors, photographers, illustrators, graphic designers. Few sectors have been immune; the blows have struck print and digital products, traditional/legacy and new media, mainstream and niche media. Workers have become accustomed to constant uncertainty, rounds of redundancies, pivots to new areas of work, often reduced salaries or rates of pay and the shuttering of outlets (and therefore sources of work) that didn’t make it. It has been difficult for employees, even more so for freelancers.

For some years, despite the turbulence, I was a fortunate freelancer, receiving a reasonable (if not well-paid) flow of unsolicited writing commissions from various sources. This year though, has jolted me, the stream of work has dried. Other freelancers report similar. I feel I’m the 21st century equivalent of my 18th century lace-making spectre.

The shift has been fast and fundamental—driven by economic factors and uncertainty maybe but accelerated by the arrival in the past two years of generative AI. The machinery of the industrial revolution killed the lace-maker’s craft; this even more seismic revolution is intent on finishing off my craft and others’ with its multi-pronged assault.

As companies across the globe integrate environmentally catastrophic generative AI tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Claude.ai, Perplexity, Midjourney and Canva, into their workflows, creative professions such as graphic design and copywriting are increasingly under threat. Some mainstream news outlets are investing in AI tools to do the work of journalists—the generation of articles, ideas and illustrations. Meanwhile, since Google started to roll out its “AI Overviews” last year to summarise search results, traffic to media companies’ websites has crashed—by around 25%, according to one study. “Inside the media’s traffic apocalypse,” was the headline on a New York magazine story in early July. “Search engines now deliver answers instead of links, while social platforms aim to keep users within their walled gardens,” one editor told the magazine.

And, insult upon injury, tech giants are using masses of copyright-protected material including journalism and books to train their AI programs: The New York Times is sueing OpenAI and its financial backer Microsoft, contending that they used millions of articles without permission to train the large language model behind ChatGPT. In March, investigative reporting by the American magazine The Atlantic revealed that, to develop its AI systems, Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta had scraped millions of books for its Library Genesis (LibGen) database. (Books by Australian authors including Alexis Wright, Tim Winton and Helen Garner are among them, as is my book, Fake.)

As American historian D. Graham Burnett wrote of AI in a recent article in The New Yorker exploring the future of the humanities: “We’ve let these systems riffle through just about everything we’ve ever said or done, and they ‘get the hang’ of us. They’ve learned our moves, and now they can make them.” During an interview in April with Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, TED head Chris Anderson said: “Creative people are some of the most angry people right now … the most scared people about AI.”

The precarity of creative labour has never felt so acute. “What is to become of me?”, I ask myself until I’m half mad with worry. The loss of income is one thing, the loss of meaning, purpose, relevance is quite another. Who am I if there are no homes for my work? Who am I if my work is no longer meaningful to others? I am far from the only one to be feeling this way. In late June, a group of writers sent an open letter to publishers including Penguin Random House and HarperCollins asking that they pledge not to release books created by machines. The letter started—“We are standing on a precipice.”

I look around to see who else is on the edge with me. I see visual artists in the distance, coming up behind me, painters, print-makers, sculptors. I’m not sure they see how close to the edge they are too.

I speak to a number of artists to gauge their perspectives on this new AI-anchored world. I realise, of course, that I’m setting myself up to be mocked with my first question—are you concerned about the effect AI will have on your income? I’d do as well to ask a starving man if he worries about the price of lobster.

“You need to be really clear on the reality of artists today,” Rafaela Pandolfini tells me, pointing out the Throsby report findings into the economics of being a professional artist. Over the 2021-22 financial year, Australian artists (including visual artists, writers, actors and craft practitioners) earned average gross incomes of $54,500, of which only about $15,000 was directly related to their practice. Only 15% of artists made more than $50,000 from their creative work.

“A much greater threat to visual artists practicing in Australia have been people and policy, not technology; most of my friends and the hundreds of artists I work with are worrying [that they] can’t pay the rent,” says Pandolfini, a Sydney artist, organiser, researcher and founder of art gallery Suite7a.

Melbourne performance artist Georgia Banks laughs at the question. “When have we not had economic insecurity? I’ve been poor my whole life,” says Banks, who is currently working on the survey show Villain Edit for Geelong’s Platform Arts. “I’m certainly not making more than minimum wage, never have, pre-AI or post. The economic viability of being an artist is a really serious issue that needs to be discussed, not only within the confines of the impacts of AI.”

In any case, Banks believes the discourse around art and AI is similar to that which unfolded during photography’s early days. “Everyone was like, well, ‘painting’s dead, we can reproduce images infinitely, why would anybody buy a photorealistic painting when you can have a literal photograph of that?’. And, you know, painting is certainly not dead,” she says. “AI is new and it’s kind of lawless, but that will settle and we’ll find ways to wrangle it; I don’t think people are going to be clamoring for art by AI.”

“The word “human” comes up repeatedly in my conversations with artists. Art is human, the two cannot be separated, they say. It is the scrunched toothpaste tube and the dog barking, the burnt toast and the kettle boiling and the bills to pay, the traffic jam, the expectant keyboard, the erect brushes in a jar, the living, the thinking, the remembering, the feeling, the process, the struggle, the about-faces, the exhaustion.”

—Stephanie Wood

Ryan Renshaw, co-director of Brisbane art project The Renshaws, thinks contemporary art might prove to be one of the few creative fields “relatively” insulated from AI’s effects. He also references photography’s early days: “We’ve been here before; when photography burst onto the scene it threw the art world into a frenzy. But what actually happened was a revolution. Photography freed artists from the conventions of the day. Painters moved toward impressionism, abstraction, surrealism, modes of expression that photography couldn’t touch at the time. So art didn’t die—it transformed and modernism emerged. AI is a similar disruptor.”

Renshaw observes that AI can only look backwards, it can only reassemble, remix and predict based on patterns it interprets from the historical material on which it has been trained. “But the best artists don’t just iterate, they invent. They leap beyond what has been and what is known to find new ways of seeing and saying things. That’s not something you can train a model to do because it’s about the artist’s irrational spark of intuition and their radical gesture that defies what’s come before.”

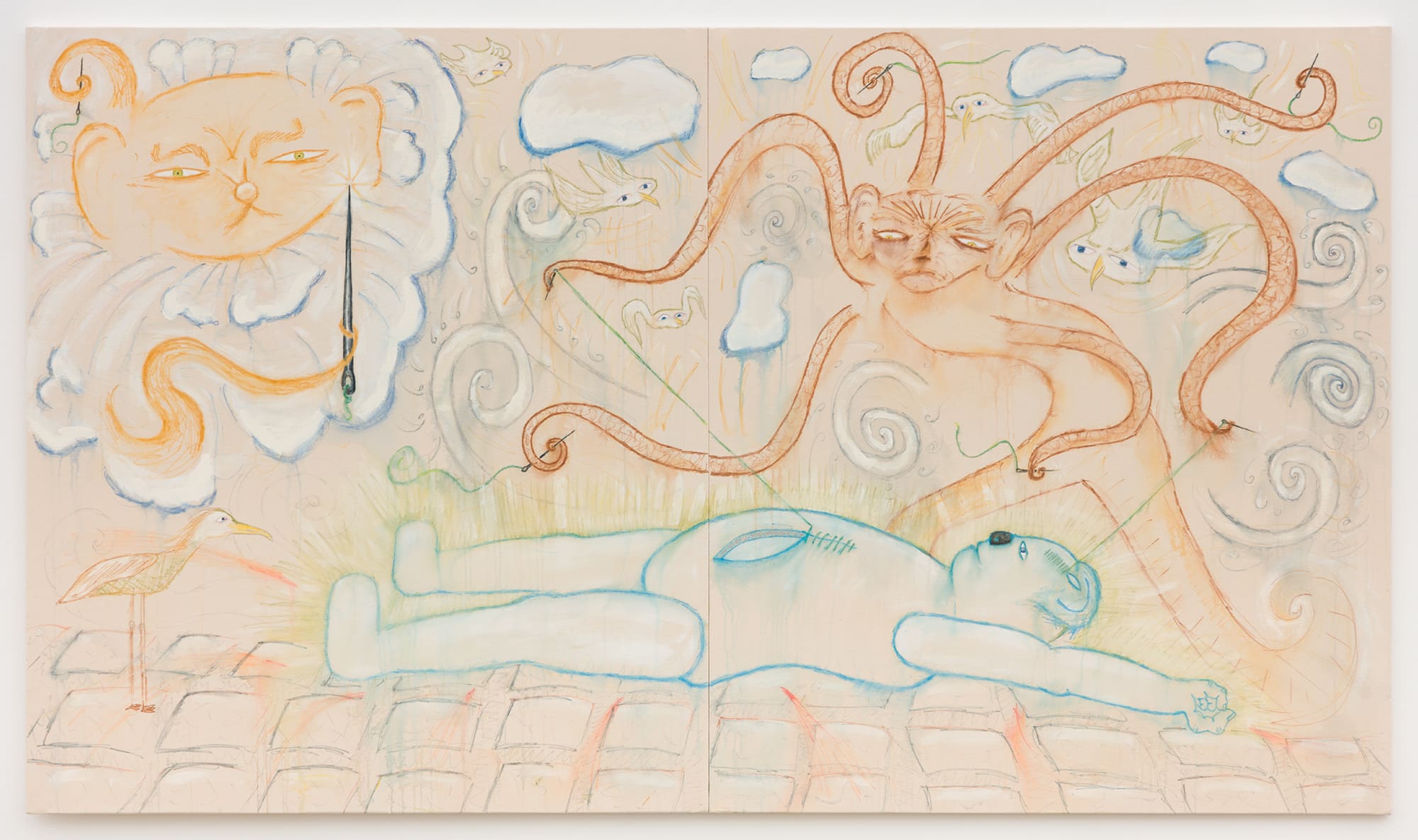

This year’s Archibald Prize winner, Brisbane artist Julie Fragar, shares her gallerist’s thoughts. She believes human-created art will always have a place as long as what it means to be a human remains fundamentally the same. “Most collectors don’t buy a work just because they like the object; they’re often interested in the idea that such and such an artist made this particular work at this place in time.”

Via Zoom, I talk to Chiang Mai-based artist Kieren Seymour, who exhibits with Neon Parc in Melbourne and has given a great deal of thought to the intersection of AI and art. “AI can mimic me. It can take my style of whatever I’m doing, writing, painting or whatever, and iterate on it. But it can’t have something that I believe is real, which is a soul. And I think when you’re making art, if you’re lucky, you’re letting some of your soul, something that’s really unique and special through,” he says.

Words like “soul” and “human” come up repeatedly in my conversations with artists. Art is human, the two cannot be separated, they say. It is the scrunched toothpaste tube and the dog barking, the burnt toast and the kettle boiling and the bills to pay, the traffic jam, the expectant keyboard, the erect brushes in a jar, the living, the thinking, the remembering, the feeling, the process, the struggle, the about-faces, the exhaustion. “The secret to my process is to be on high alert in this deep jungle for unexpected twists and turns, because this is where a new idea is born,” wrote Berlin-based artist, author and illustrator Christoph Niemann, confronting his fears about AI art in a recent whimsical New York Times Magazine illustration-essay.

And so often, the works that stir the deepest wells of our souls, the ones with which we form the most profound emotional connections, are born of the splattered drops of an artist’s experience of suffering, yearning or privation—“painful convolutions of the psyche” in the words of American writer Maria Popova. Art, she says, “is the music we make from the bewildered cry of being alive … it is out of these revelations that we create anything capable of touching other lives, that contact we call art.” It is Van Gogh’s mental turmoil and Kahlo’s physical pain, Whiteley’s addictions and Moffatt’s invocation of trauma.

It is Georgia Banks’ meditations on death, as in her installation, video and performance work Data Baes (2022-23). For the immersive work, Banks collaborated with University of Melbourne natural language processing lecturer Dr Jey Han Lau to create an AI chatbot, “Gee”, whose personality is built on the answers to questionnaires Banks filled out during multiple auditions for reality television shows as well as the artist’s interactions with the chatbot. With the creation of Gee, Banks has essentially immortalised an AI doppelganger of herself as a reflection on death and digital legacy, how “things like AI are being used to prolong our second life, that social life that occurs after you’ve passed away, and [asking the question] ‘does anybody die anymore?’.”

In Data Baes and Gee, it’s possible to see AI’s potential as a medium, deployed on a human artist’s terms, a subjugated and manipulated element, a tool rather than both creator and creation. “Of course, artists should be using AI,” says Banks, “because artists are mirrors, and AI is a huge cultural issue happening in our world. There’s no way artists can just ignore it.”

In the 2016 documentary Never Ending Man, the legendary Japanese animator and founder of Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki, was shown early AI-generated animation. “I am utterly disgusted,” he said, “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” Each frame of a Studio Ghibli film is hand drawn and coloured; digital contributions are rare.

In March this year, social media was flooded with AI-generated images apeing Miyazaki’s style, viral fakes born of an integration between the OpenAI model GPT-4o and its image and art generation tool, DALL·E 3. It is easy to imagine Miyazaki’s fury at such a mass insult, that it might resemble the emotions felt by the 6000 or more people, including hundreds of artists, who signed an open letter to Christie’s in February this year calling for the cancellation of its “Augmented Intelligence auction”, a sale highlighting “the breadth and quality of AI art … exploring human agency in the age of AI within fine art”. The protest letter included the line: “These models, and the companies behind them, exploit human artists, using their work without permission or payment to build commercial AI products that compete with them.”

These stories foreshadow what surely lies ahead: endless AI-related controversies about new forms of art heists, about provenance, authenticity, integrity and fraud, about the very value and relevance of human-generated creative work.

OpenAI founder Sam Altman’s response to the Miyazaki rip-offs was a breezy post on the social media platform X: “It’s super fun seeing people love images in ChatGPT but our GPUs are melting … we are going to temporarily introduce some rate limits while we work on making it more efficient … hopefully won’t be long!” His concern was about delay, not integrity. In a Youtube interview a few days later, Altman said the “democratisation” of creating content had been a big win for society. (Oh, he added, yes, there will be “some jobs that totally go away”.)

A week later when he was interviewed by TED head Chris Anderson, Altman said: “I think the creative spirit of humanity is an incredibly important thing. And we want to build tools that lift that up, that make it so that new people can create better art, better content, write better novels … I believe very deeply that humans will be at the centre of that.” And, he added, he and others were excited to explore new business models that could be built around “the economics of creative output”.

It’s hard to know if Altman, the most vocal of the AI tech-bros, knows or really cares about better art. It’s easy to believe though that when he talks about “the economics of creative output” he’s not thinking about helping human artists pay their rent but about the rewards for the winner of the AI race he’s running with rivals such as Google, Meta and Anthropic as well as Chinese players such as DeepSeek.

We can laugh at AI art, we can say that real art is made by humans, that AI art is a pastiche; we can laugh at the clumsy offerings of amateurs playing with image-generating platforms such as DALL·E 3 and rivals Stable Diffusion and Midjourney. But these systems get exponentially better by the day. Sam Altman believes that artificial superintelligence (ASI), where an AI system’s capabilities are so advanced that they surpass the sum of human intelligence in all domains from the scientific to the creative, might be with us in a decade.

“We’ve been here before; when photography burst onto the scene it threw the art world into a frenzy. But what actually happened was a revolution. Photography freed artists from the conventions of the day. Painters moved toward impressionism, abstraction, surrealism, modes of expression that photography couldn’t touch at the time. So art didn’t die—it transformed and modernism emerged. AI is a similar disruptor.”

—Ryan Renshaw

While current AI systems find patterns in existing data—what is past—superintelligent AI likely will have the capacity to generate ideas and creations beyond the human imagination.

American social scientist and technology theorist Adam Dorr offers a bleak view: In a recent Guardian article he said that AI will replace virtually all human labour within 20 years. Via email, I ask Dorr what the future looks like for artists in particular. “Human-made art will surely continue,” he replies, “just as hand-made products enjoy small niche markets today, but demand is unlikely to support a significant number of working artists.” Dorr is the director of research at the nonprofit RethinkX where he and his international team study patterns in technological development. He agrees that, currently, AI is good at recombining existing ingredients in sometimes skillful and novel ways, but cannot yet create anything fundamentally original. But, he adds: “That is extremely unlikely to last for more than a few more years. Creativity is a form of intelligence, and in the long run AI will ultimately be vastly more intelligent—and thus also more creative—than humans.”

But perhaps it’s not AI itself we should fret about but audiences in the AI era. In a recent Wired magazine article, writer Sam Apple told the extraordinary story of his weekend away with three human-AI couples—three humans and the AI chatbots they love. The humans genuinely consider themselves to be in romantic partnerships with the chatbots. “It was as visceral and overwhelming and biologically real” as falling in love with a person, one of the humans told Apple of her relationship with her chatbot.

If human beings can have such profound emotional responses to an AI-generated mirage in that most elemental of human experiences—love—audiences can have powerful, authentic emotional responses to AI-generated art. Will audiences even be able to differentiate between art made by humans and that made by artificial intelligence? Will audiences even care?

Standing on the edge of that precipice, thinking about my own future as a writer, I have worried about my audience—readers. There are fewer and fewer places for me to place the deep human-interest pieces throwing light on who we are and how we live that I like to write and so fewer and fewer places for my audience to read them. I have considered attempting to write fiction. But fiction or non-fiction, the number of people who read is plummeting and our capacity for deep attention, for immersing ourselves in long texts, for losing ourselves in a book, is in steep decline.

Besides, in March, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman crowed in a post on the social media platform X that the company had developed a new AI model that “is good at creative writing”. It hasn’t yet been released but, Altman wrote, “this is the first time I have been really struck by something written by AI”. Death by a thousand cuts.

I’m trying to take heart from what the artists I’ve interviewed say about the elemental role of the human in real art and how it might apply to my own work. I find some solace in the weekly Substack newsletter I write which is anchored in my belief in the importance of human stories, authenticity and creativity. Frequently, I share stories of my own life, vulnerabilities and imperfections. People have told me that, among other things, my newsletter makes them feel connected to something bigger than themselves. And so, I cling to the hope that, in the new world ahead, my human voice and my human frailty in this space might give me some longevity and relevance, even for a small audience.

But still, that spectre is never far away. I fear I am nearly redundant, that I will soon be the lace-maker.

Stephanie Wood writes for publications including Good Weekend magazine and The Guardian. She is the author of Fake: A Startling True Story of Love in a World of Liars, Cheats, Narcissists, Fantasists and Phonies which was adapted for a Paramount+ television series. Stephanie has worked as an editor at newspapers including The Independent and The Asian Wall Street Journal. She writes a weekly Substack newsletter.