Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Born in 1957, South Australian artist Gerry Wedd is known for his ceramics as well as his long-term graphic contribution to the iconic Mambo brand, beginning in the late ‘80s and ending in 2006.

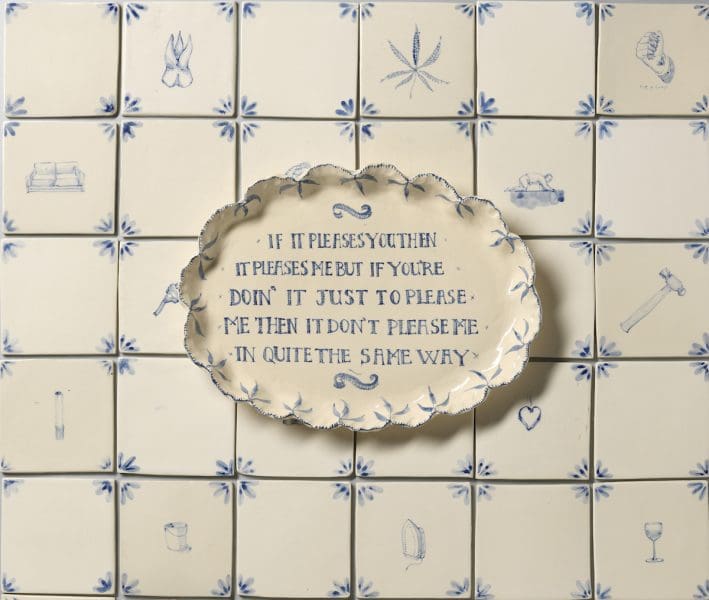

Wry and witty, his classical ceramic forms draw on surf culture, politics and cult music in their surface decoration. Blue and white willow pattern plates might sport the face of Paul Kelly or Dolly Parton, or barrelling surf à la Hokusai. Among the objects in Wedd’s popular Kitschen Man exhibition, which travelled the country after debuting at Adelaide’s JamFactory, a burnt orange vessel features a lone surfer, rendered like the black figures or melanomorpha, on antique Greek pots. Wedd is very much aware of the canon of his chosen medium while subverting its traditions to make pithy declarations. In his latest exhibition, Song for a Room, Wedd has built an entire room, comprised of a thousand handmade tiles bearing text and imagery.

VK—Where did you grow up? How did you wile away the hours as a child?

GW—My father built a modest asbestos home at Port Noarlunga an hour or so from Adelaide which was an idyllic seaside holiday destination at the time. Life was based around the beach, drawing and reading and making odd figures of heroes from plasticine. My strongest memories are of dozing in the sand hills after surfing, listening to the static of the waves in the warmth.

VK—You were exposed to ceramics through your mother who was a hobbyist, when did you get serious about the medium?

GW—Although I started drawing on pots for my mother in my late teens I was always a bit embarrassed about the idea of pottery, particularly her kitsch earthenware approach. I have eventually and unavoidably morphed into her. It wasn’t until I was nearly 30 that, with much encouragement and some flattery and coercion I enrolled at art school.

VK—What are the intrinsic qualities of the traditional cobalt and white of Delft that make it suitable for what you want to say to the world?

GW—There is a great and complex history of decorating with cobalt across time and cultures, from Iranian pots to the Willow Pattern and Delft, this makes it an ideal vehicle in that it is wide open culturally. I don’t feel I’m stepping on anyone’s toes. I was always a bit uneasy about the holus-bolus appropriation of ‘Sino-Japanese’ techniques and approaches to ceramics in a Western context.

VK—In Song for a Room you use text and drawings on ceramic tiles to comment on the ordinary and bizarre moments that make up daily life. Many of these draw on life in the home – what themes here are following on from Kitschen Man?

GW—The whole project borrows heavily from historical precedents – Mexican Talavera, Persian, Spanish, Portuguese, Delft, and English blue and white tiles. The Delft tiles in particular feature wide and varied illustrations of everyday life and familiar objects. I like the democratisation of imagery and the sly humour incorporated in some of the tile paintings.

They have the potential to be read and decoded through time and use. In some way they make less demands than a piece of art (perhaps).

VK—From a tiled interior space, the works explode outwards to take in Australian pop culture with song lyrics from the likes of the obscure ‘60s band The Loved Ones, Nick Cave and a host of others. What is your intention in bringing in drugs and rock and roll to this medium?

GW—I am more a folk and country listener really but the lyrics of popular songs are an endless source of interest for me and always have been. The narrative nature of songs have made them great stepping off points for me when decorating pots.

For this show I have taken snippets of lyrics that when isolated can act as mottos, epigrams or aphorisms, and I have painted them onto the tiles. In some ways it is riffing on the banal kind of affirmations that we seem to be bombarded with. There is a tile from 1800s Iran in the Victoria and Albert Museum that I love and probably first saw 20 years ago. In 2015 I had a residency in London and when I made the pilgrimage to the tile, I discovered that it was part of a group of tiles illustrating a Persian love poem with image and text.

VK—Of the 1000 handmade titles in this show, do you have a couple of favourites?

GW—There are some tiles that split that I have come to like more and more; one with a crack leading to a little dead bird in the tile’s centre, another with the same kind of crack leading to a skinny nude man. The thing that keeps me interested in this activity is the vagaries of process and the gap between the idea and the outcome.

VK—The exhibition was inspired by Victor Hugo’s extraordinary tiled dining room in Hauteville House in Guernsey (one of the Channel islands). During his 15 years in exile, Victor Hugo not only wrote masterpieces like Les Misérables but found time to decorate his home.

GW—The first time I saw the image of his dining room was in a copy of the magazine World of Interiors some years ago. The image stopped me in my tracks, and then I read that it was from Hugo’s dining room. I was already a big admirer of the Delft and Mexican use of tiles in interior spaces but there was something about the convergence of an intellectual and decorative aesthetic sensibility that intrigued me (I have an aversion to modernist taste).

VK—You are donating half of the proceeds from the sale of the works in Song for a Room to the Adelaide Day Centre for Homeless Persons. How did you come to this decision?

GW—There has always been a tendency for me to use pots as vehicles for ideas or stories. In the last 20 years I have snuck some social commentary onto my work. I am well aware that a cup with a boatload of refugees painted on its side isn’t going to change the world, but I feel the need to do it, and because ceramics lasts for ever it will be a constant reminder of events that occurred at the time it was made.

At the beginning of this project I realised that I was constructing a temporary shelter with Australia Council funding which made me feel a little uncomfortable. By selling the work and passing on part of the proceeds I have a rare opportunity to help an organisation doing great and necessary work.

Song for a Room

ACE Open

28 July—15 September