Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Tiarney Miekus: What draws you to painting?

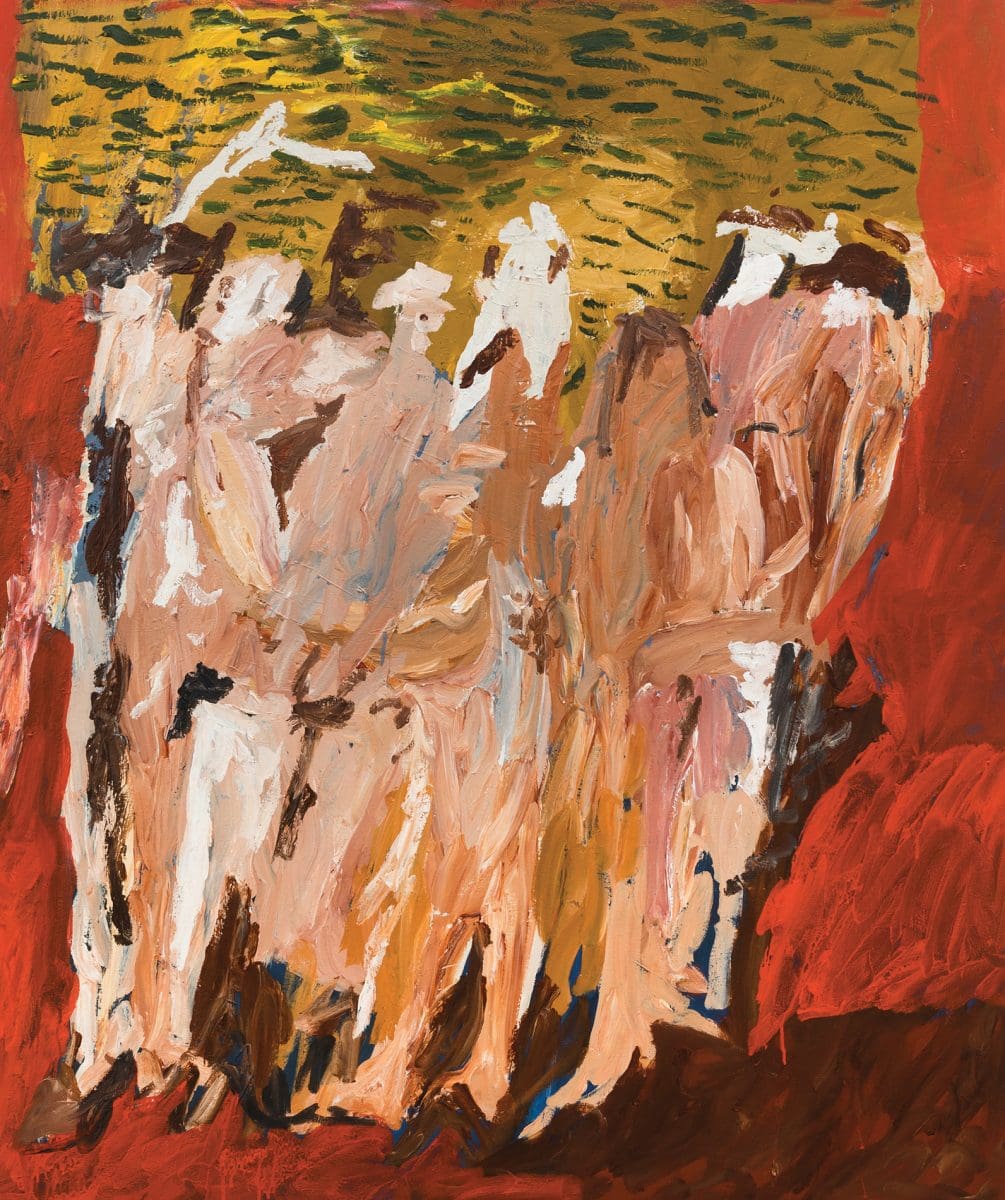

Georgia Spain: That’s a big one. There’s something really magical about painting that’s unlike other mediums, to me anyway. There’s an element of surprise and constantly trying to find the unknown in it. There’s something about the exploratory nature of it that I really love. But I’m also drawn to the immediacy of making a painting. It’s something you can do on your own.

TM: Did you grow up in an artistic family?

GS: I did. My parents are both in the arts. My dad’s a printmaker and an artist, and my mum has worked in publishing for a long time and has worked with children in the arts. It’s definitely been fostered and nurtured from a pretty young age and it’s a valuable thing to spend your life doing, which I’m pretty grateful for. It’s a privilege to say “I’m going to be an artist,” and have the confidence to do that.

TM: You recently moved to regional Tasmania. Has that influenced the painting?

GS: The main thing the move allowed is for me to be full-time painting and dedicate most of my time to working on my practice. Living in the city in the past, I’ve not had the time to do that: it’s always been working multiple jobs just to pay rent and have a studio. And then it’s inevitable that wherever you are influences what you put out. I’m not a landscape painter, but the beautiful landscape that I live in must affect my work in some way.

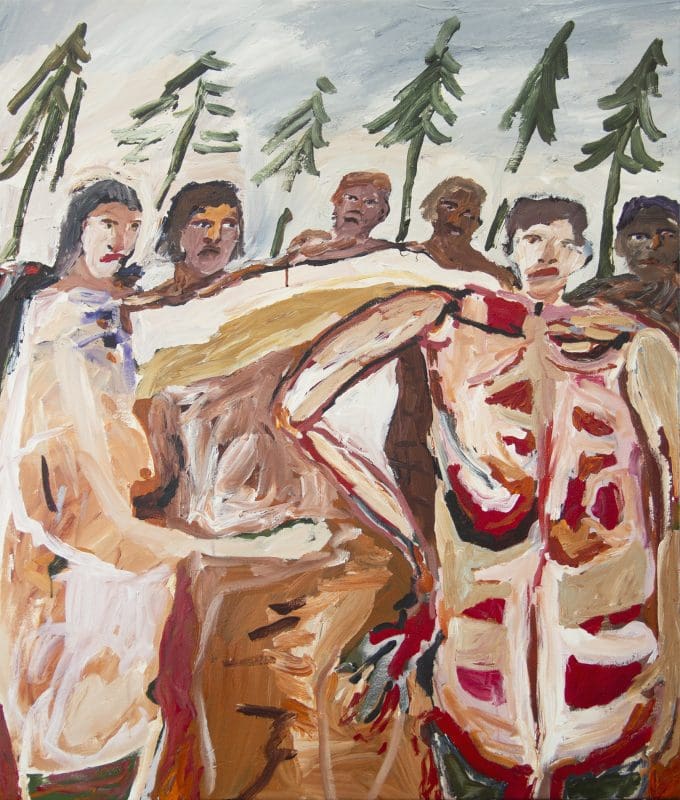

TM: You often capture people in group situations— what compels you to such scenes?

GS: I’m interested in group dynamics and the way that we come together as people—I think it’s really interesting particularly in times of crisis, or when we have to come together. There’s a very human need to come together and be—it sounds a bit corny—but be as one and put aside our differences. I’m also interested in relationships and trying to capture the intimacy and the nuances of the way we interact with each other.

TM: When you’re trying to capture that ‘oneness’, your paintings also feel so gestural and embodied, that it seems like they hang on a compositional precipice.

GS: Like a splitting of the painting?

TM: More like you can’t believe how the composition comes together.

GS: I think that’s the nice thing about painting, that there’s this possibility within it: that you can create an image that is impossible in the real world. Like the merging of people that I paint, almost but not quite melting into each other—that’s something that paint allows you to do.

TM: For Six Different Women, which won the Women’s Art Prize Tasmania, are they women you know?

GS: No, that painting was inspired by the story of the Maenads, Dionysus’s female followers in Greek mythology, who roamed the mountainsides in a wild and carefree manner. I was hoping to depict a more tender moment between the women, showing a more intimate side to the story that touched on ideas around friendship and the strength of female bonds.

But I think my figures are becoming more and more ambiguous in terms of not being specific people, but being more representations of people.

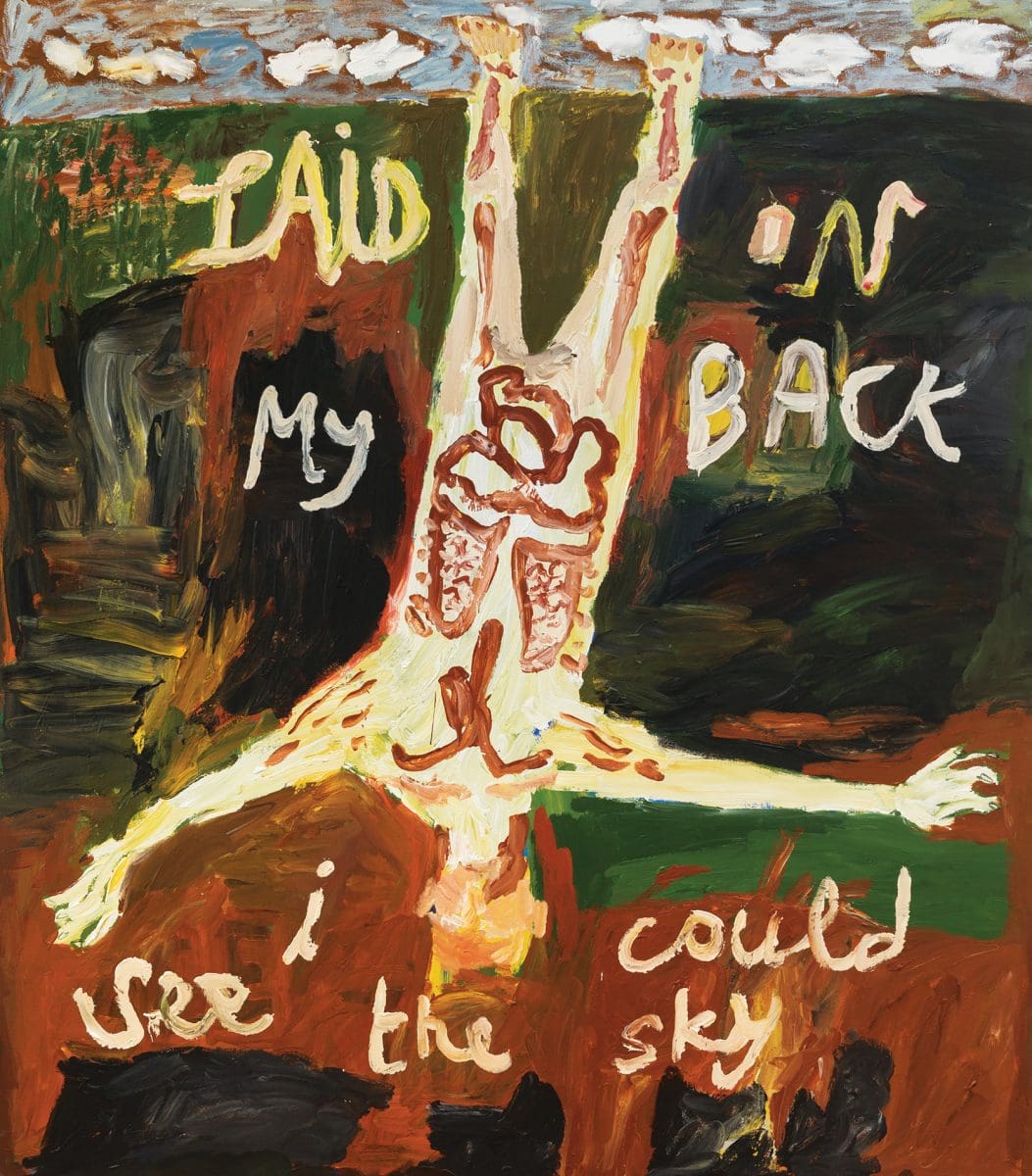

TM: In the work Getting down or falling up, for which you won the Sulman Prize, you’ve again captured people together but in a way you’ve defined as both pleasure and conflict. Intuitively I feel like these go together, but what’s the link for you?

GS: They can both be scary places to be in. They’re both moments in which we’re vulnerable or we’re open to something. But I know what you mean: it’s kind of hard to put your finger on it, what that actually is. I suppose it’s also how we interpret an image depending on how we’re feeling at the time. Like that painting can feel like a moment of conflict if that’s what you’re bringing to it, but it can also have a sense of bodily fluidity, or maybe a bit of sexuality in there. But any painting is going to have multiple readings depending on your own life experience and where you’re coming from at the time.

TM: I was reading that you collect many images, particularly family photographs. Why do they resonate for you?

GS: I suppose there’s an element of nostalgia that is inherent in all art making. At the moment I’m exploring memory and how to access memories. And with the childhood images, I’ve always had a slight yearning for that feeling of being a child, or the nostalgia of a bygone time. It’s something I’m constantly trying to access. So even if I’m not using the family photographs at the moment, in terms of trying to explore that idea of looking back at my own life, painting is a way to process or find that. It’s worth noting this is also linked to my story, which is that my sister died nine years ago. I think that wanting to re-access that time of being young is a way for me to connect to her.

TM: That kind of profound grief can find its way into art in very oblique ways. Like it’s overwhelming and it’s there, but it’s not specifically the subject matter.

GS: For sure. It’s not like, “Here’s this picture that’s about grief.” But any kind of huge loss like that is going to affect your whole life and anything that you make is going to be informed by it—although not identified by it. I don’t want to ever see it as my identity, but it’s a huge part of who I am.

TM: You’ve talked about wanting your paintings to be accessible. Do you think accessibility is an issue in contemporary art?

GS: I think it’s an issue. To me, if I can’t get something from a work without having to read the room sheet, then I feel like there’s something wrong. Well, not wrong, but I guess on a broader level a lot of people feel alienated by ‘contemporary art’ and they’re like, “Oh, I don’t understand it. There’s something I need to understand, and I don’t.” And that’s partly why I love painting because I think everyone can understand it. It’s more the feeling of a painting, or the meaning that allows people to connect with it. But I do think that figurative painting is always going to have an accessible way into it because people recognise a human figure.

TM: You’re quite young for the success you’ve had. What’s that success like before age 30?

GS: Good question. Well, I guess it’s true on paper that I’ve had lots of success, particularly this year.

TM: I guess we can define this success as careerist.

GS: Yes, career success, which doesn’t really change the feeling of being in the studio and trying to paint and being like, “What am I doing?” It’s a bit ‘angsty artist’ to say this, but the hardness of trying to make art doesn’t go away just because I’ve won a prize. Of course, it’s lovely to be recognised and it definitely feels validating to be like, “Oh, other people like what I’m doing.” But it doesn’t really affect my daily studio life that much. I still feel like I have the same struggles that I’ve always had.

TM: As someone relatively at the beginning of their own career, what advice would you give to someone who wants to be an artist?

GS: Just work hard. And this is really cheesy to say, but don’t worry about what other people are doing or thinking. I think that’s what has been good for me, and part of the reason why I’ve had recognition and success in the last little while, is that I have just continued to do what I want. And not worry too much about whether it’s cool or on trend or whether people are going to like it.

Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2021

Gippsland Art Gallery

8 October – 21 November 2021

Women’s Art Prize Tasmania

Rosny Barn

8 October—31 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.