Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

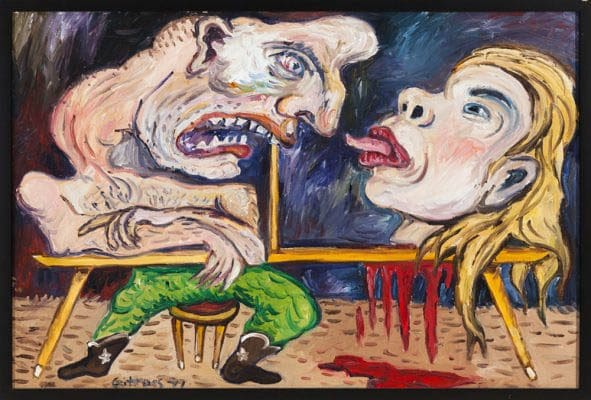

Sydney-born artist and filmmaker George Gittoes makes art wherever there is conflict, including: Rwanda, Bosnia, Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan. At 66, he shows no signs of stopping and the accolades are piling up, including the Bassel Shehade Award for Social Justice, 2013, and the Sydney Peace Prize, 2015. Works spanning his 45 year-long career can be seen in his current survey show, I Witness, but it is the work that he has helped others make in the toughest of circumstance that makes him the most proud. Steve Dow asked Gittoes about the past and present Yellow Houses, making art in war zones and staying optimistic.

Steve Dow: You co-founded the Yellow House artists cooperative in Potts Point in 1970. What are your strongest memories of that formative period?

George Gittoes: Martin Sharp had been in London with Oz magazine, rock and roll and the Beatles and Cream, and I had been lucky enough to be in New York and experience Andy Warhol’s Factory and the civil rights movement, hippies and the Vietnam war. We both arrived back in Australia and it was the most dead place on Earth. We wanted you to walk through the doors and be transported. It was a time of high energy and giving Sydney a bit of what we’d been lucky to experience in London and New York. By the end of the night we’d have people doing whirling Sufi dances around the Brett Whiteley pictures and other great art.

At the end, we were invaded by barbarian hippies who thought they could take a tab of acid and sit in a storm water drain, and that was as good as experiencing great art.

Martin and I decided we should be doing [art gatherings] in Vietnam, during the height of the war, to bring about change. Neither of us knew how to do that. It’s taken me a long time, but finally, god bless him, Martin was still alive when we were doing it, we’ve made it happen in Jalalabad, in Afghanistan.

SD: Yellow House in Jalalabad, set up in 2010, teaches film and television and has backed the making of Pashtun-language dramas and TV. Why do you love Afghanistan so much?

GG: It’s got nothing to do with Afghanistan. I just love creating a model in which art can make a difference. It costs $1 million for every soldier Australia puts on the ground in Tarin Kowt, and they train young men to use guns. Now those same soldiers are using the training to destroy the country and work for ISIS, bandits and kidnappers. The kids that we’re training [in film and television], some have actually been kidnapped by ISIS, and they’ve come back and said, ‘Well, instead of using a weapon, we’re going to use a camera.’

There’s a worldwide trend of artists coming together in places like Palestine and Cambodia to show that art can make a difference. It’s art without borders.

SD: How are you funding Yellow House in Jalalabad?

GG: Yellow House is sending me to the poor house. Every cent that I make from the sale of my art goes into funding the Yellow House. It’s so hard to apply to organisations for more money that I find it’s easier to make a painting and sell it.

SD: Are you philosophical about the dangers to your life in war zones?

GG: I’ve just written a book for Pan Macmillan, it comes out in late September, called Blood Mystic. Just as the gay movement people came out, I’m coming out as a mystic. My experience of the other side is just so strong that I just don’t fear death. I relate very much to the Sufis and shamans and the people in the cultures I come from who say we’re on Earth to learn who we are and what we are and facing death is a very fast road to learning why you’re alive.

SD: Are you optimistic or pessimistic for the future of social justice?

GG: I’m an absolute optimist. In the long time I’ve been doing this work I’ve witnessed all these great triumphs of the human spirit, like Mandela in South Africa, I was there on the day of his rainbow speech. I’ve been there with a lot of Australians when they’ve made things happen in Cambodia, the first elections, East Timor. I was in Northern Ireland at the height of the troubles, and people said this would never end, the hate is too deep. But it did come to an end.

SD: What’s your next international trip?

GG: I’m off to Brazil in August. I’m going to assist another group working in the favelas of Brazil. Then I’m hoping to do a sequel to my [2006] movie Rampage [a documentary set in Miami ghettos]. America just hasn’t gotten any better, even under a black president, so I want to be in the US when the elections are happening, and highlight how little has changed for blacks. In Miami, which we associate with South Beach and luxury, there are places that are poorer than Soweto.

SD: In 2013 you had surgery for prostate cancer and a double knee replacement. How long do you see yourself working in war zones?

GG: I’ve worn my body out in a lot of ways. I worry about my exposure in war zones to chemical agents, particularly depleted uranium dust from the weapons used in Iraq. I just want to keep doing what I do until the day I die. My whole life has been based on a letter Mother Teresa wrote to me in 1972, after I’d written to her when I was disillusioned about Yellow House in Sydney, when it had become a place where all these hippies take a trip. She wrote back and said, use the talents God has given you for others, and you’ll end up a very fulfilled person. That’s true. I’m 66, I’m happy and fulfilled.

George Gittoes: I Witness

Penrith Regional Gallery

Until 21 August 2016