Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

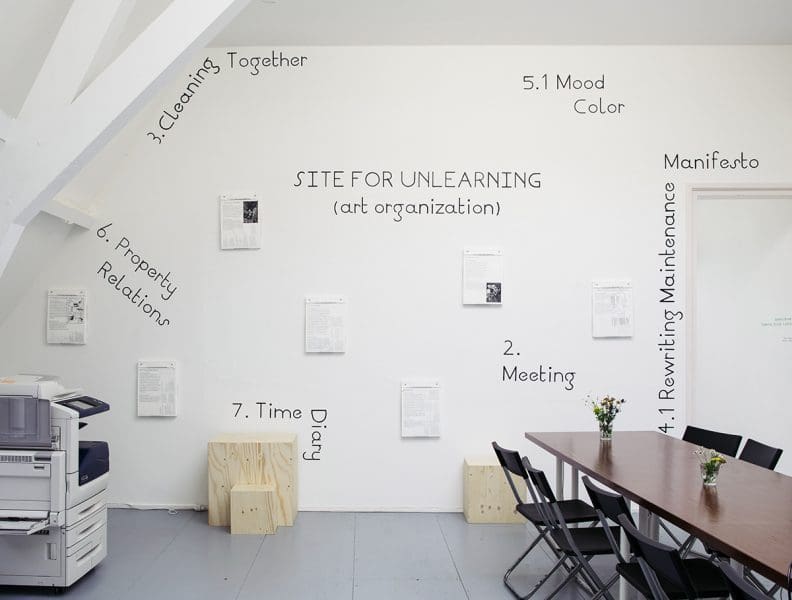

A Centre for Everything is a socially-engaged creative project operating at the intersection of art, learning, food, play, and activism. Melbourne-based, it was created by the artist duo Gabrielle de Vietri and Will Foster. Their latest project will feature in Shapes of Knowledge at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA). The museum describes the exhibition as “reflecting on how we live, how we learn, and the unique ability of art to animate our sensory experiences and critical faculties.” Rebecca Shanahan spoke to Gabrielle de Vietri about their work in the show, Maps of Gratitude, Cones of Silence and Lumps of Coal, a sharp, multi-pronged, and at times satirical, assessment of the visible and not so visible relationships between the fossil fuels industry and public art institutions, including those attached to universities.

Rebecca Shanahan: How did this project come about?

Gabrielle de Vietri: As the urgency of our political times has caught up with us, we’ve become more direct about what is important for us to do as creative, engaged individuals and communities.

Especially with the exhibition happening just before the election, we felt we needed to drop everything and focus our energy on being part of a global solution for the issues we’re facing.

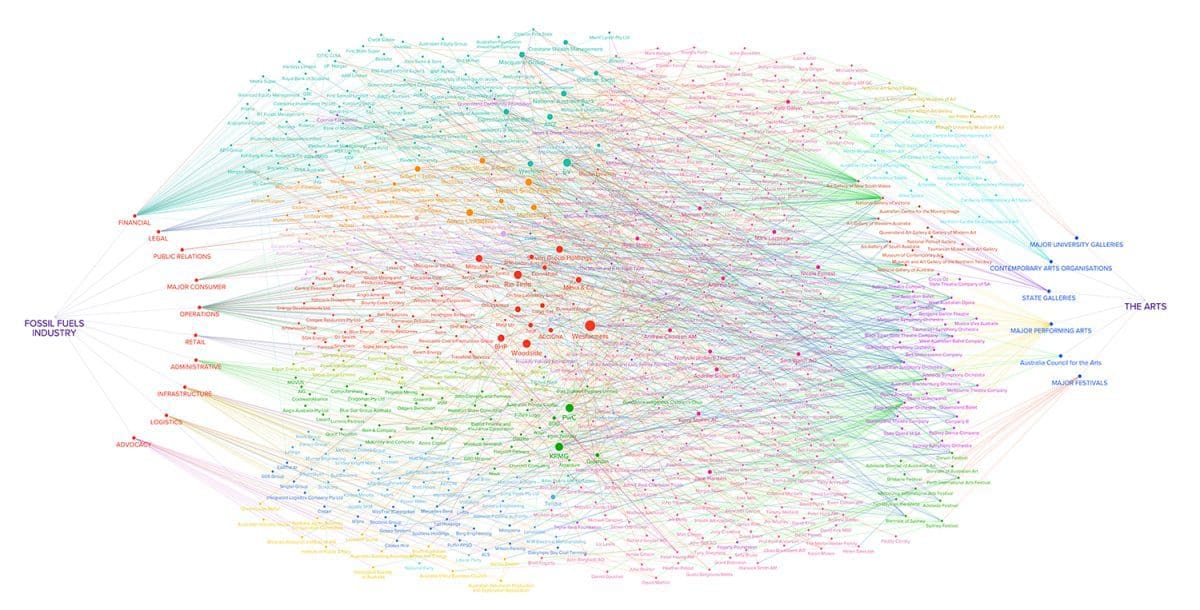

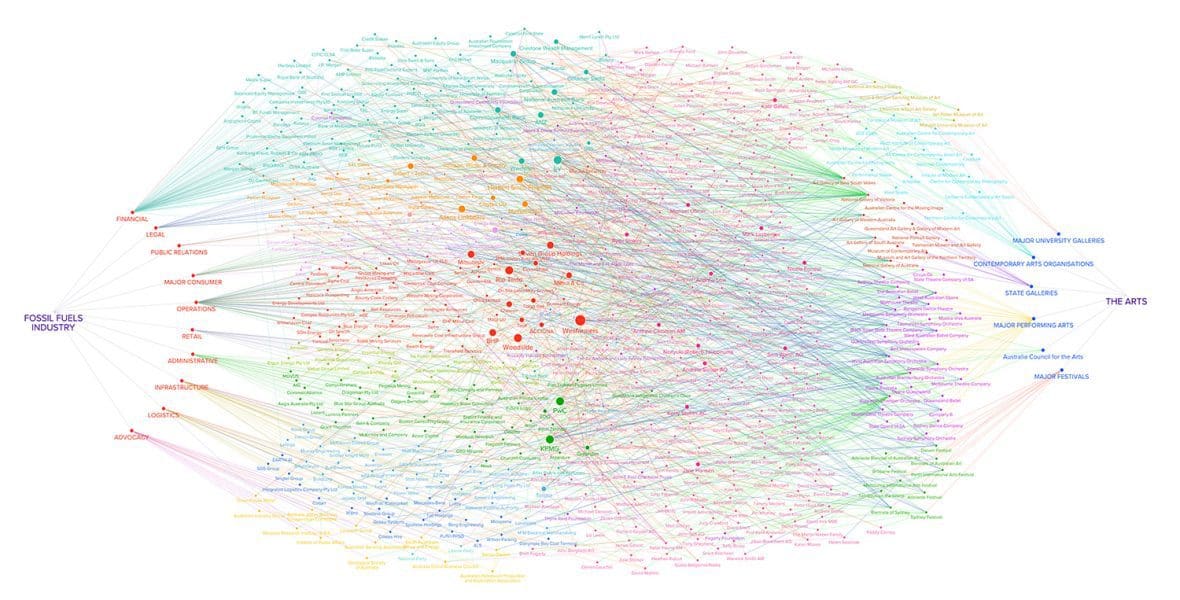

The fossil fuels industry is the single biggest contributor to carbon emissions and they are also big sponsors of the arts in Australia. Fossil Fuels + the Arts (network map), 2019, looks at the connections between the fossil fuels industry and the arts. We focused on the state galleries, major performing arts, major university galleries, contemporary art organisations, biennales and festivals.

Across the institutions we researched there were 14 oil, gas and coal companies (like BHP, Wesfarmers and ExxonMobil) that directly sponsor the arts as a way to satisfy their corporate social responsibilities. We see this as how they buy their social licence to operate, and a way of doing business. Then there are the companies that service, fund and enable their activities.

We hadn’t expected to find so many sponsors that didn’t appear to be part of the fossil fuels industry, but that in fact play an important role in its survival. For example, some of the big administrative and legal firms have dedicated oil and gas departments that support the continuing extraction of fossil fuels and they are also major sponsors of the arts.

Fossil Fuels + the Arts (video lecture), 2019, unravels and explains some of the most interesting discoveries that we’ve made in that map: why fossil fuels companies sponsor the arts, why arts organisations accept their money, and the implications of that relationship.

RS: So this is investigative journalism as art process?

GdV: In a way. It has been an in-depth research process, but we tell the story as artists. We think it’s time that artists and arts institutions examine our complicity in this system – we are effectively a marketing arm of the fossil fuels industry.

As artists we pretend it’s none of our concern, but there’s another ‘social practice’ going on in parallel to our own artistic practices, which is more powerful than whatever we think we’re doing.

RS: I assume there is an irony within the title phrase Maps of Gratitude?

GdV: The title relates to the comment that Malcolm Turnbull made about the “vicious ingratitude” of the artists who withdrew work from the 2014 Biennale of Sydney. I was one of those artists… I’ve been trying ever since to see if making art can have the same effect as not making, or withdrawing, art.

RS: You’re socially engaged artists, but there’s also your sculptural work, Coal as Ice, 2019, in the show. Tell me about that.

GdV: There’s a public artwork in Perth that Gina Rinehart and Hancock Prospecting donated to a suburban shopping mall with a poem inscribed on it, called ‘Our Future,’ written by Rinehart. It’s a manifesto for mining. We were fascinated by the mining industry’s attempt at making a public artwork, so we’ve looked at that sculpture, along with the lump of coal Scott Morrison brought into parliament, and created a lump of coal that also doubles as an ice cream cart. We’ve developed an organic vegan coal ice cream to be served from inside the sculpture.

RS: It actually contains coal?

GdV: Yes – it’s edible. Our sculpture/ice cream cart goes to places where the relationship between business, arts and the fossil fuels industry is murky, and performers serve coal ice cream and expose the way in which the coal industry ingratiates itself with the Australian public.

It’s framed as a gift, a way for the fossil fuels industry to say “thanks for your support” to the arts community. The service personnel will tell audiences that coal is so clean you can eat it. They will explain the virtues of coal, including that coal can now “reduce its emissions by up to 40%” according to the Minerals Council of Australia, and that if you eat it, you can reduce its emissions even more.

While some people have been outraged at the stunt, others have accepted the coal ice cream without question, feeding it to their children and nodding enthusiastically when they are told that it comes courtesy of the fossil fuels industry.

RS: So it loses its ironic and parodic qualities when you take it away from an informed audience?

GdV: Perhaps. Or perhaps we need to amp up the absurdity even more to make the discomfort of that relationship a bit more jarring.

RS: What do you want people to get from this show?

GdV: Awareness, and then reform. We want conversations to start between artists, arts workers and directors of institutions. Are we sure we want this relationship between the fossil fuels industry and the arts to exist? Do we want to accept their money and their governance and in exchange grant them their social licence to operate? I don’t think that relationship has been examined closely enough.

Shapes of Knowledge

Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA)

9 February – 13 April