Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

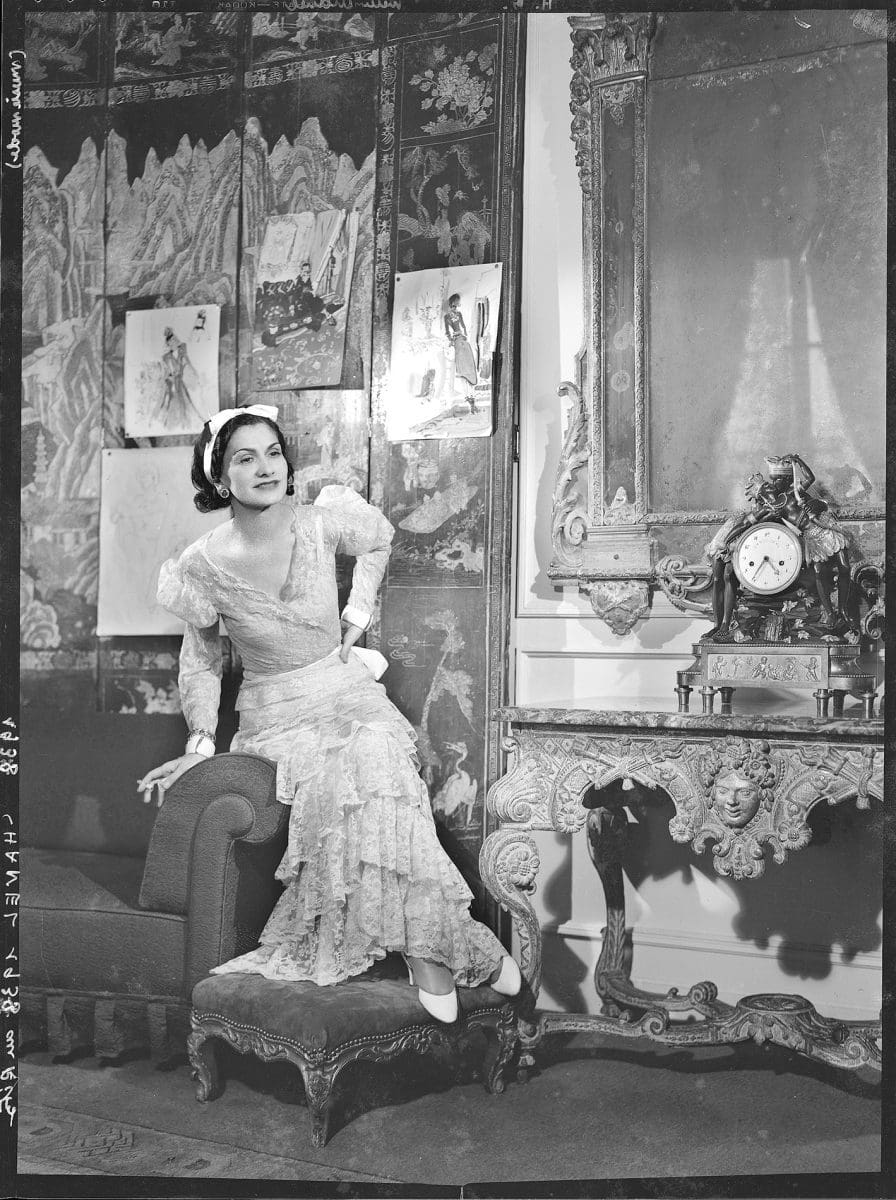

A collaboration between Paris fashion museum, Palais Galliera, and the National Gallery of Victoria, Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto marks the first time a major retrospective of the designer’s work has been seen in Australia. Following an initial showing in Paris in autumn 2020, Melbourne is the show’s first international stop.

“This exhibitionis an opportunity to connect with Chanel, a female designer who was one of the most influential couturiers of the twentieth century,” says Danielle Whitfield, curator of Fashion and Textiles at the NGV. With over 100 pieces sourced from across the NGV, the Palais Galliera and Patrimoine de CHANEL in Paris, the exhibition includes examples of Chanel’s signature braided tweed suits, the 2.55 quilted flap bag, two-tone pumps and costume jewelry.

Set out in chronological order, the exhibition traces Chanel’s substantial oeuvre from the sailor blouses and daywear created for her Paris couture house at 31 Rue Cambon, through to her later designs for Hollywood film stars and French New Wave cinema. Red, white, black and gold form an enduring palette that lasted Chanel’s entire professional career. “There is a vocabulary of colour with Chanel and there are moments in the exhibition where we acknowledge this. We have some gilded garments from the 1960s made from fabrics like gold lame lurex that imitate metal.” The eponymous Little Black Dress is a dominant feature of the exhibition, as Whitfield explains. “Black was used relentlessly in the 1920s and 30s, yet the way Chanel was using it in designs like the LDB spoke of modernity and it became part of her iconography and design language of the house.”

Trained as a milliner, Chanel rebelliously shunned the restrictive corsets and frills of the Belle Époque and Edwardian fashion in favour of garments focused on comfort, function and style. Responding to the growing independence of women, Chanel saw a need for clothing mirroring this societal change. Embracing her own independence and ambition, in 1928 Chanel began to manufacture textiles through the Tissus Chanel Company, allowing for a thoroughly holistic and unrestricted approach to fashion design.

“At the time, Chanel’s use of fabrics like tweed and jersey were not associated with couture womenswear” says Whitfield. “A code we talk about with Chanel is the transposition of the masculine into a feminine wardrobe—borrowing from the language of men’s suiting, the outerwear and tweeds worn for sports like golf and hunting. There are elements of pragmatism and functionality to Chanel’s designs but always a refined sense of aesthetics as well. It was like creating a uniform for the modern woman.”

Chanel’s design language extended beyond clothing, with her iconic perfume, Chanel No.5, considered revolutionary when it was released in 1921. “It’s very similar to how she approached her clothing design, it completely goes against what was conventional at the time,” Whitfield points out. “Previously perfumes were heavy, floral scents in really ornate bottles. Chanel worked with perfumer Ernest Beaux to blend a scent that is really abstract and elusive, and its presented in a plain angular bottle. It echoes the style of her clothing which was about restraint and simplification of design.”

Chanel also devoted time to designing jewelry and accessories, with many of her pieces subtly referencing moments in art and design history. “Jewelry was an opportunity for Chanel to explore her interest in symbols,” says Whitfield. “White camellia flower brooches and pendant crosses used materials inspired by Byzantine glass mosaics and her travels to Venice. Chanel was able to use elements from history and make something modern, it was all part of building up a design language with garments and then adding other iconography through perfume and jewelry.”

Despite working in the early-mid 1900s, Chanel developed an aesthetic that has remained a part of women’s fashion for more than a century. Whitfield puts it down to the timeless quality of her minimal designs and the revolutionary changes Chanel made to female fashion. “There are archetypes we continue to associate with Chanel and they are centred around notions of comfort, understated elegance and ease of movement. The way we approach dressing today owes a great debt to Chanel.”

Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto

NGV International

5 December 2021 – 25 April 2022