Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

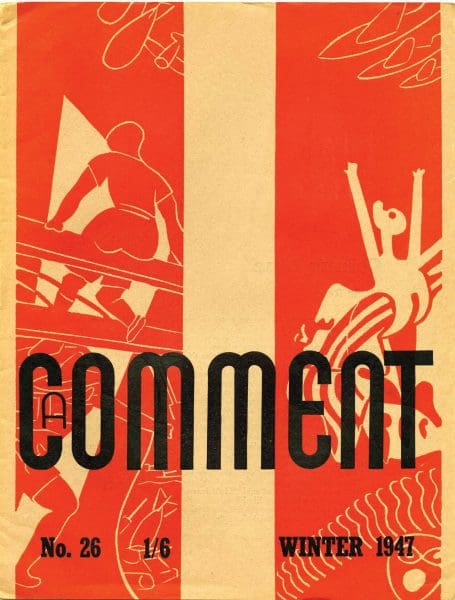

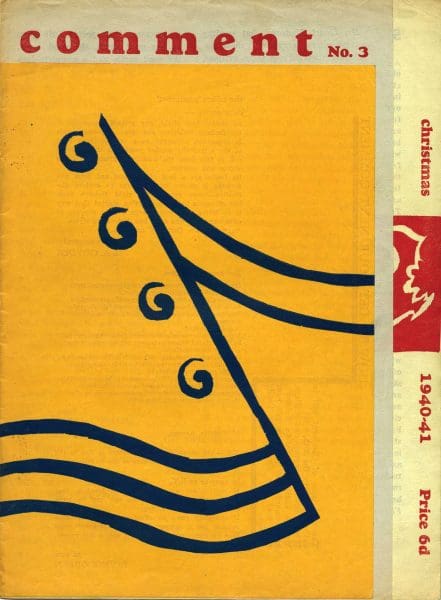

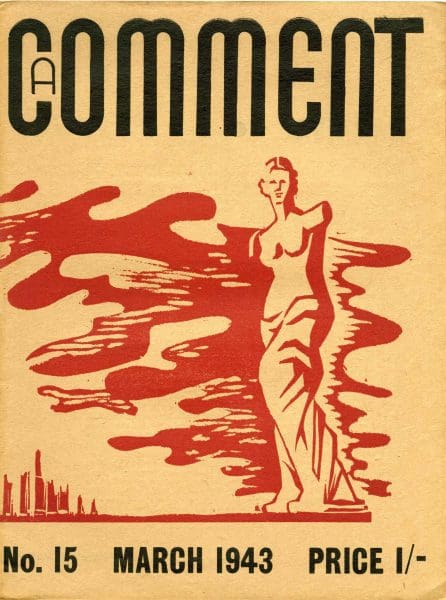

The linocut covers of A Comment literary magazine, which ran from 1940 to 1947, were not remarkable purely in and of themselves. What is remarkable is the entire output. Considered one of the most radical, self-published, Australian arts and literary magazines from the 1940s, A Comment’s simple cover designs were usually printed in just one or two colours. Although their sparse design may not be a prime example of the linocut medium, they speak to the ingenuity of the magazine and its editor, Cecily Crozier.

Crozier wanted the bold designs to catch the eye of the right sort of people. The covers were modernist-bait, and the trap was set for local avantgardes by laying the magazine among the periodicals of only the hippest bookstores in Melbourne (where it was published) and Sydney (where the artists Carl Plate and James Gleeson distributed it).

For the value of their cover designs (rather than the experimental poems, stories and criticism held inside), Crozier’s magazine covers feature in the second iteration of the National Gallery of Australia’s successful exhibition, Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now.

A Comment was launched by Crozier when she was 28 years old. She had grown up in an itinerant family that moved across Asia and Europe, spending the majority of her adolescence in the south of France. It does not appear that she had any experience as an editor or arts worker, outside of artist modelling in London in her mid-20s. Like her magazine, Crozier’s intentions were community-driven; she wished to help stimulate the arts scene around her.

The magazine’s companion publication was the better-known Angry Penguins, another Melbourne-based literary magazine of the time. Although A Comment was published slightly earlier, the two shared many writers. In terms of printing, World War II resource rationing meant that the cover and internal papers were comprised of drab brown paper-stock. Crozier and her husband Irvine Green used linocut as a cheap, effective way to enliven the poverty of the material with bold, colourful designs. A wobbly line here or there (especially in the first few issues) was not a problem. In fact, the hand-made quality of A Comment was its calling card–it was seeking a niche audience with local innovators. In one editorial Crozier celebrates the achievement of 300 subscribers. This was a magazine intending to speak directly to a community of peers, and the amateur linocuts were a signal of its grassroots sincerity.

Yet not only was Crozier not the creator of the striking covers (those illustrated are by Green or Robert ‘Menkhorst’ Miller), but she also complicated her role as literary editor, writing in her second issue: “Another thing. We said in our first issue that Comment had no editors, and this is why. If people are doing something new there are no standards by which to criticise their work.” Crozier had hoped that A Comment would be so literally avant-garde, so ahead of the cultural zeitgeist in Melbourne, that there would be no peers qualified to judge it—not even herself. In a later memorialisation of A Comment, Melbourne poet Alister Kershaw reflected that, despite Crozier’s protestations, “she certainly made a blithe and venturesome non-editor.”

Despite its niche readership, A Comment was able to find allies outside of its Sydney and Melbourne circles. The American poets Karl Shapiro and Harry Roskolenko were stationed in New Guinea during the war, and took their recreation leave in Australia. After coming across A Comment in a local bookshop, Shapiro was blown away. “A COMMENT should be shown in America. It is brave and good—as good as our best—and really a signpost in a world of destroyed art,” he wrote. Both Shapiro and Roskolenko published in A Comment, and both fell for its charismatic ‘non-editor’: Crozier was fun, entertaining artists and poets in her suburban home, where they debated and played piano late into the night.

The do-it-yourself nature of A Comment extended beyond the humble materials or handwrought aesthetics it accepted for itself. Flicking through issues, it is hard not to be excited by the enthusiasm of Crozier and her peers. You can imagine Crozier sitting at her kitchen table, receiving poems and prose for the next issue, picking out which colour ink to use for the text, which for the linocut. In issue four she puts out the challenge: “Why not let “Comment” be the battle ground upon which YOU will fight for your ideals and ideas.” But A Comment is more a passionate love letter to the arts, than a declaration of war.

Reading biographies of Melbourne art world figures in the decades around World War II, one is struck by the women who kept the scene running. Crozier stands among important female personalities like Sunday Reed, Katharine Susannah Prichard, Helen Ogilvie, Cynthia Reed, Nettie Palmer, Dorothy Braund, Lina Bryans, Ruth McNicoll, Nina Christesen, and Elizabeth Vassilieff. Not all these women are artists, so only some show up in Know My Name, but they all helped make creativity in Melbourne possible.

The do-it-yourself quality of A Comment is still inspiring today because, as Kershaw bluntly put it, “hordes of people are interested in the arts— or claim to be—but damned few of them show any inclination to spend their time and energy, let alone their money, running magazines.”

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now

National Gallery of Australia

12 June—26 January 2022

This article was originally published in the July/August 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.