Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

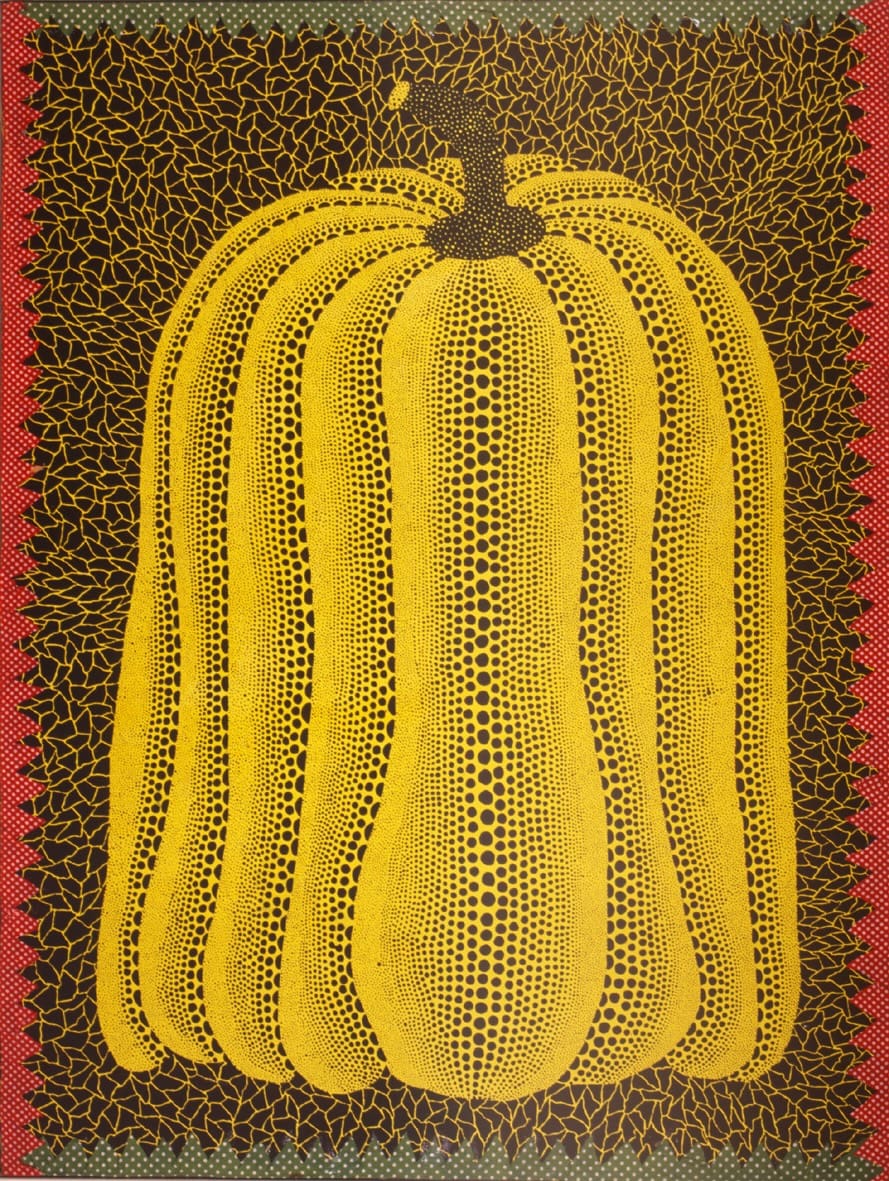

Mirrored galaxies that unfurl in all directions. Polka dots that seem to dance mid-air. Pumpkins rendered in Crayola colours that touch on something childlike in our consciousness. The work of singular Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama is remarkable for its ability to transcend language and reflect what it means to be human. In her art, darkness coexists with a capacity for joy and play and wonder. This December, the National Gallery of Victoria will premiere Yayoi Kusama, the largest-ever presentation of the artist’s work in Australia, featuring 180 works including the artist’s latest Infinity Room and a newly staged version of her legendary 1966 installation Narcissus Garden.

Ahead of the show, Art Guide invited four artists to respond to the influence of Kusama on their own practice—and meditate on what her work means to them.

Etude—Love song for Kusama Yayoi Sensei

Dear Kusama Yayoi Sensei,

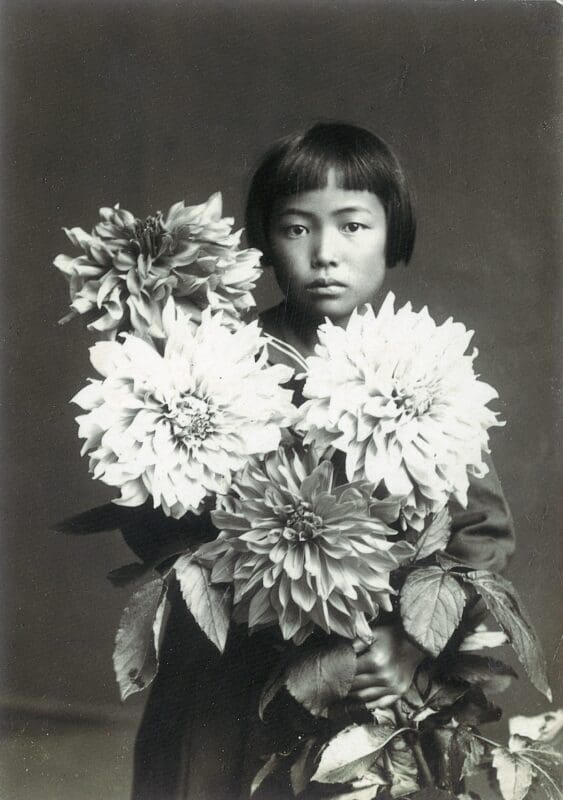

If this love song may ever reach you by any chance, I thank you deeply for freeing us. You have long been an inspiration and role model for me, as you have courageously used your art to open conversations about mental illness in a loving and generative way—in spite of societal taboos. Your expansive interior worlds have the power to bring us all into the beauty and chaos of your mind, which mirrors our minds in 2024.

I have always admired how you use art to learn how to live with the hidden monsters I believe are living in each of us. [Your] proliferation of dots, lights and colours seem like a prayer for peace and harmony, while also providing a means of exorcising the cacophony of voices within. It becomes a beacon of hope for others who are struggling with internal chaos. The discipline of creating countless points of light as a means of quieting the mind generates a feeling of infinite beauty and calm.

As an artist with lived experience of anxiety and obsessive behaviours, I am so deeply grateful for your commitment and bravery. I want to continue to believe in humanity. I will continue to sing love songs with you.

With love and deep gratitude,

Sincerely yours,

Hiromi

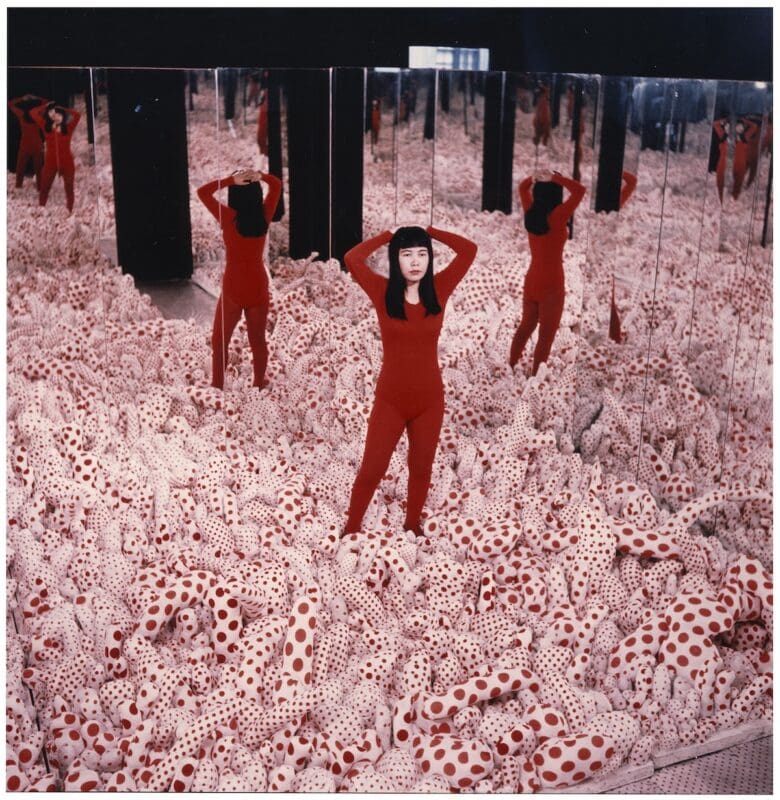

In the early 2000s I remember visiting the Queensland Art Gallery and poring over the early 60s photographs of Yayoi Kusama. She was so sexy, and peaceful looking—partially nude, with heavily made-up eyes and covered in dots. From the ground level, I could hear the orbs in her Narcissus Garden clinking against each other as they bobbed about in the water. Kusama had made her own world, one in which she made perfect sense. I was in awe.

Kusama’s disgust of heterosexual sex first led her to cut out, stitch and stuff hundreds (thousands?) of phalli in the early 1960s. She attached them onto furniture and everyday objects to form surprising sculptures. Through the repetitive acts of making her big thick worms she transmuted her fears [and] they became something funny.

Infinity Mirror Room Phalli’s Field (1965) is the first installation in which Kusama used mirrors in a way that sectioned off the known world. In her own words, the mirror’s repetition created “endless space”. The phalli (stitched out of red polka-dot cotton fabric) form a kind of landscape, and Kusama walks, stands, or lies in the field. The mirrors in Kusama’s Infinity installations also serve to place us, her viewers, completely within the realm of her imagination.

Yayoi is sitting in her studio waving at us. Endlessly making, forever and ever.

Surrounded by her work she seems happy and content—the work is the work. Here paintings are covered in loops and marks, nets that will envelop her and eventually us. It seems to me that this is the place where Yayoi might be happiest, in that space of no time—the studio.

When I think of Yayoi, I think about this impulse to work and the drive to transform. In all her work the idea of the horror vacui is apparent—every surface, every object, and in her Infinity Rooms, air and space itself is covered in repetitive marks, colour and shape. In some works, like her Obliteration Rooms, you become the obsessive and impulsive one but it’s always her guiding principle.

It’s in her paintings that this obsession seems most direct and personal—from her 60s webs and nets through to her recent work where searing colour and pattern burn its way onto the retina. It is labour made manifest, fecund and overwhelming. It’s a state to aspire to.

Hello Yayoi, I am waving back to you.

Endlessly making, forever and ever.

Kusama’s Narcissus Garden is a prophetic work that anticipated the fusion of art, self-reflection, and commodification. First shown in 1966, just a few years after the Soviet launch of Sputnik, her silver orbs evoke futuristic imagery. Much like the satellite reflecting the world back at its viewers, Kusama placed these orbs at the Venice Biennale, presenting the audience with their own image.

Narcissus Garden astutely suggests that one of the things people often seek from contemporary art is the feeling of being the sort of person who engages with contemporary art. This is especially true at events like the Venice Biennale, where attendance itself becomes cultural capital.

The orbs’ mirrored surfaces showed people this interaction long before social media allowed people to record and display their cultural participation. The multitude of orbs reflected and re-reflected the images thousands of times, [as if they were] being reposted in real time. Kusama went further by selling the orbs during her performance, allowing viewers to take a piece of their self-reflective experience home, or back to their super-yacht.

Though quickly halted by event organisers, this act prefigures her complex relationship with art’s commercialisation. Narcissus Garden critiques the commodification of both art and identity, offering a prescient view of the entanglement between cultural capital and late-stage capitalism—an ongoing theme throughout Kusama’s career.

Yayoi Kusama

National Gallery of Victoria

15 December—21 April 2025