Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

“Art to me is the celebration of impermanence,” Francesco Clemente once said. This is the core – the unadorned final pip of a Russian doll in his significant oeuvre that spans some four decades. His paintings dissolve at the edges both in the literal washes of paint and in their concerns – the elusiveness of memory and nostalgia.

Clemente was born in Naples in 1952 and first visited India in 1973; he now divides his time between Varanasi, India, and New York City. As such, notions of the exotic loom large for the artist, not as the ‘other’ but as a meeting between the self and surroundings. The ‘exotic’ is intimately experienced and then processed through his work.

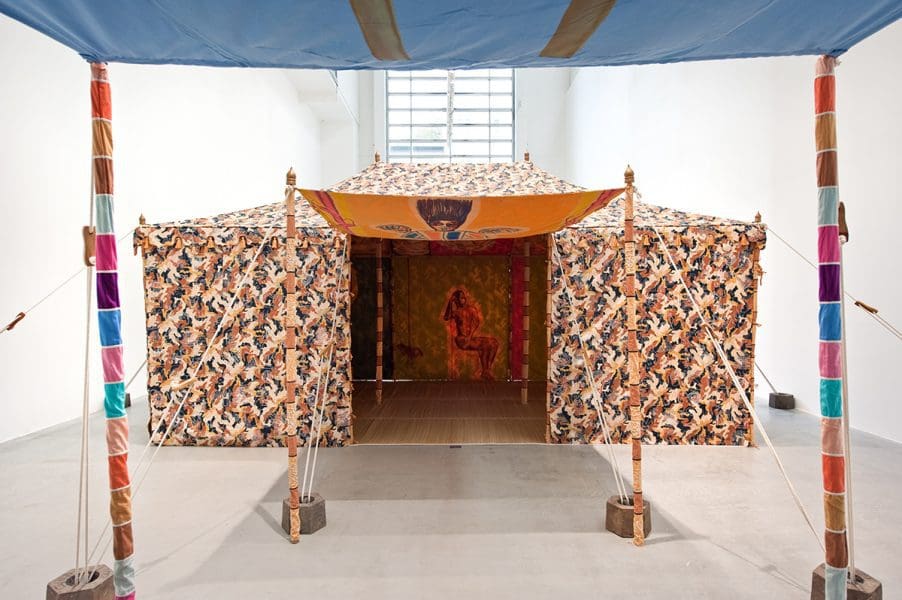

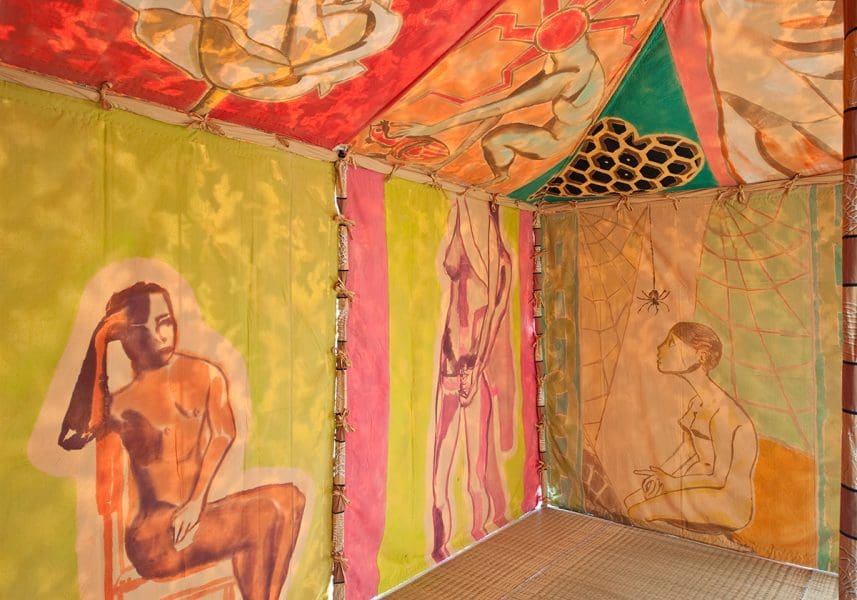

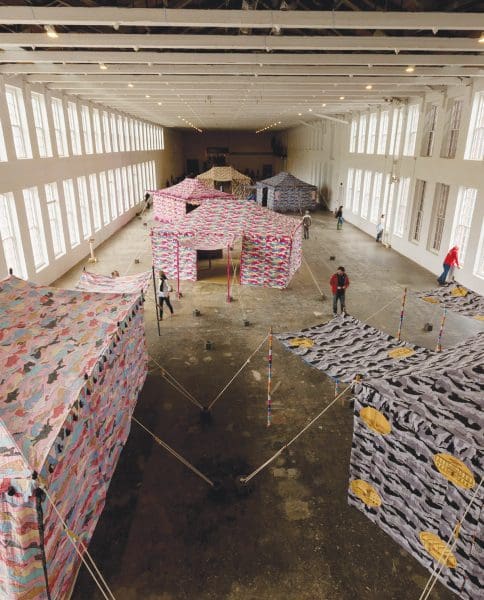

Working closely with Indian artisans in Rajasthan, Clemente hand-printed the tents’ exteriors with/using woodblock and embellished them with gold thread over the course of three years. They may cause one to pause; the “densely patterned tents”, says curator Nina Miall, are “commanding” even in their setting: 30,000 cavernous square feet of exhibition space. The act of stepping inside the tent deletes the venue; Clemente’s tempera angels, self-portraits, erotic imagery and figures, which are at once corporal and spiritual, now enclose the viewer.

The tents are sequenced, opening up narratives, as the artist suggests, becoming “a short story of making and unmaking an identity”. The viewer here is very much an active participant: even when faced with a tent wall of Clemente’s self-portraits, they not only see, but also are seen. Miall adds, “The tents are intended to be briefly occupied by visitors… they offer a transformative experience to the viewer.”

“It is the encampment of imaginary tribes,” Clemente said when Encampment made its first stop at Mass MoCA last year. “Maybe these 108 works are the book of these tribes.”

Tents are loaded with meaning and are flexible in function – as a place to rest, to see a spectacle, to find refuge, to call home; they appear in forms ancient, exotic, utilitarian and increasingly high-tech. In the case of the Occupy movement or a humanitarian crisis, they become political. As such, Taking refuge is the name of the third space in this work, though it only struck Clemente that tents are “where refugees actually live” later. His process is creation first, research second.

After completing the work, Clemente picked up a Bible and scoured historical Western paintings of battle scenes for depictions of tents. As in Exodus, the tent is also a tool of escape from enslavement: “And thou shalt make an hanging for the door of the tent, of the blue, and purple, and scarlet, and fine twined linen, wrought with needlework”.

Alongside the tents are four sculptures, appearing like sign posts or altars that reference contemporary life. Of these, Hunger, 2014, speaks of today’s enslavement – the culture of consumerism. Emblazoning a flag are Debord’s words, which call out the alienated modern condition: “The spectator feels at home nowhere, because the spectacle is everywhere.”

Despite this, a sense of joy permeates Clemente’s work as well as his words. “If you have a past,” he begins in a 2012 video by the Tate Gallery, “you will believe in the future, that the future will be more interesting than the present.” Optimism – rendered in vivid colour and in scenes where winged figures experience pleasure under pastel pink umbrellas – reigns in Encampment.

The interiors of the tents are rendered in a stylistic extension of the neo-Expressionism movement that Clemente helped pioneer in the 1980s, side by side with such luminaries as Anselm Kiefer and Julian Schnabel. A counterpoint to minimalism then as they are now, Clemente’s figurative paintings are rich in narrative detail and symbolism. Prolific in his output, he painted hundreds of works for Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 film Great Expectations and has had recent shows at the Uffizi Gallery, Guggenheim Museum and Centre Pompidou, just to name a few.

Also set to be exhibited is the series of 19 paintings No Mud, No Lotus, named after the contemporary Buddhist text on the transformative nature of suffering. Clemente, says Miall, has “repeatedly looked to Eastern philosophy and spirituality as a way of escaping Western materialism”. The series, “inspired by Mughal miniature painting and painted in a limited primary palette of royal blue, crimson and yellow”, continues Miall, features what appear as cuts or bodily orifices. The works ripple with the erotic pleasure–pain binary and tread between Indian and Western influences, while bordering on abstraction.

The works in Encampment are a kind of geographic mapping of Clemente’s own life. Though wary to accept the term ‘nomad’ for himself, the artist has created a bejewelled transit stop, to fill up spiritually and visually.

Encampment

Francesco Clemente

Carriageworks

30 July – 9 October