What makes an object remarkable? A few things come to mind: historic legacy, cultural significance, the ability to conjure evocative memory. Powerhouse Museum have covered it all in 1001 Remarkable Objects—an ambitious exhibition spanning decorative arts, jewellery, costume, textiles, furniture, clocks, musical instruments, industrial design and social history. Here, the curatorium team share with us some of their favourite objects in the collection, and the stories behind them.

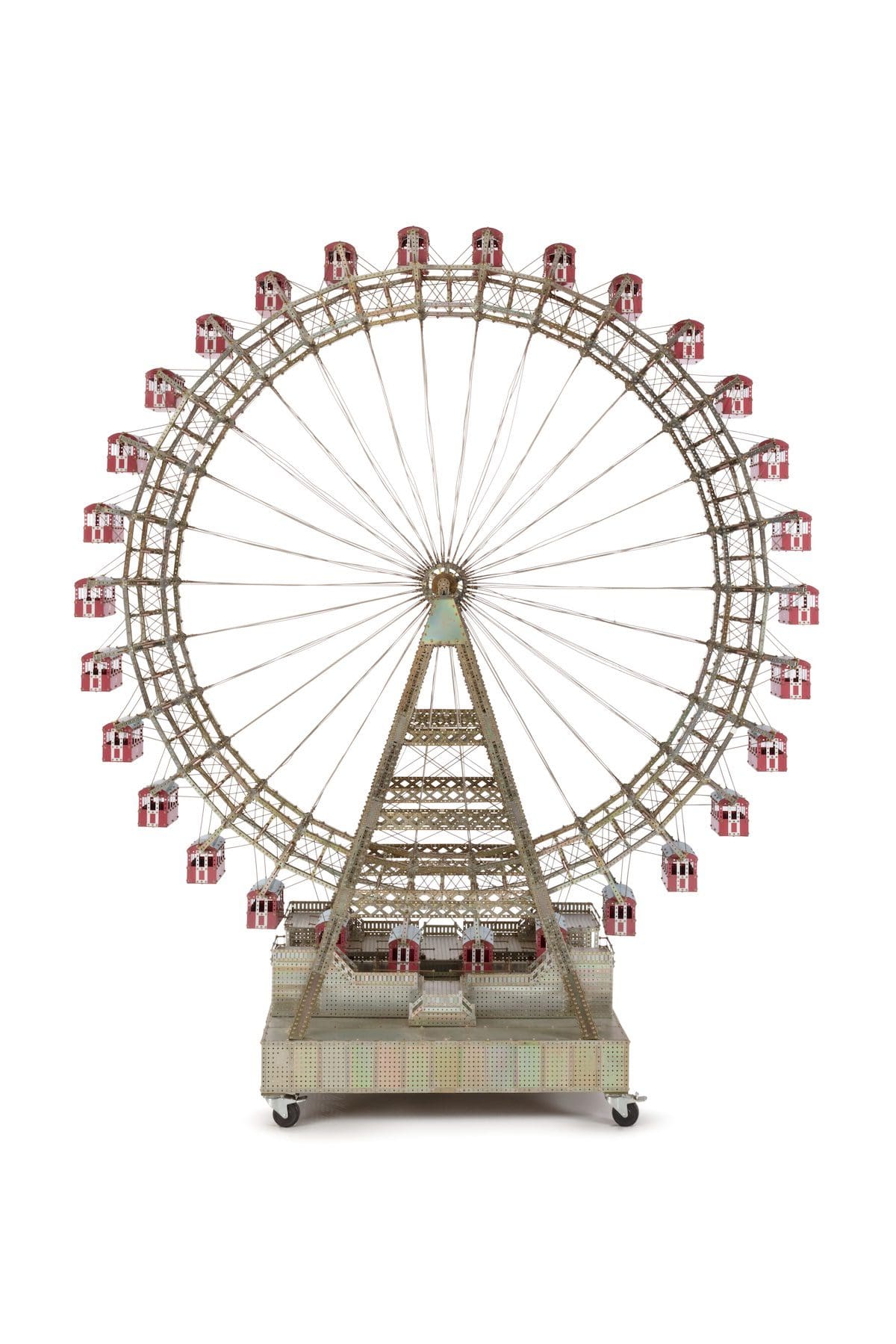

Leo Schofield AM: Large Meccano model of Ferris Wheel in Vienna

The first and most famous Ferris wheel in the world was built in 1897 at the entrance of the Prater amusement park in the Austrian capital, Vienna. Still in situ today, it has become something of a symbol of the city, notably featuring in the celebrated film by Carol Reed, The Third Man. It spawned similar wheels, all much bigger, around the globe—from the so-called London Eye to Tianjin,Tokyo and Las Vegas.

A humbler but no less imposing replica is the Meccano model in the Powerhouse collection, patiently assembled by Fred Lane, an avid Meccano collector and builder. Fred received his first Meccano set as a boy, and describes how he could “smell” the Meccano waiting for him under the tree at Christmas time. In a newspaper interview in 1998 he recalled, “waking up those Christmas mornings to the lovely aroma of Meccano parts. It used to conjure images of magic in them and it reminds you of your youth, when life was much more simple.”

When Fred retired to Murrurundi, in the Hunter region of New South Wales, he built an addition to his new home to accommodate his magnificent Meccano collection, the pride of which was this replica now housed in the Powerhouse collection and displayed here for the first time, a truly remarkable object.

Mark Sutcliffe: Love is in the Air: Kewpie Doll

It was 1 October, 2000. Sydney had hosted the 2000 Olympic Games and the Olympic Stadium at Homebush was ready to party at the Closing Ceremony. Australian icons paraded around the stadium and performed on stage. Celebrating the 1992 film Strictly Ballroom, giant kewpie dolls arrived on the field, along with 960 pairs of ballroom dancers performing to John Paul Young’s Love is in the Air. I was one of those dancers and it was an electric moment to celebrate the end of the Games and mark this special event in Australian sporting history.

The kewpie dolls were designed by Brian Thomson. There were 12 in total and each were named by the prop makers. This kewpie is named Scarlet. Although not directly connected to the film, the skirt is made of green crinoline and tulle with red trim and sequins, so added to the visual spectacle of the performance.

The kewpie dolls evoked the fun of fairground attractions of old, but also provided a link to Australian literature as they were centrally featured in Ray Lawler’s 1955 play The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll. It was an unforgettable moment for me personally, that was shared with the country and the world. It seems only appropriate that Scarlet takes pride of place overseeing the 1001 collection, which helps celebrate our cultural history and milestones.

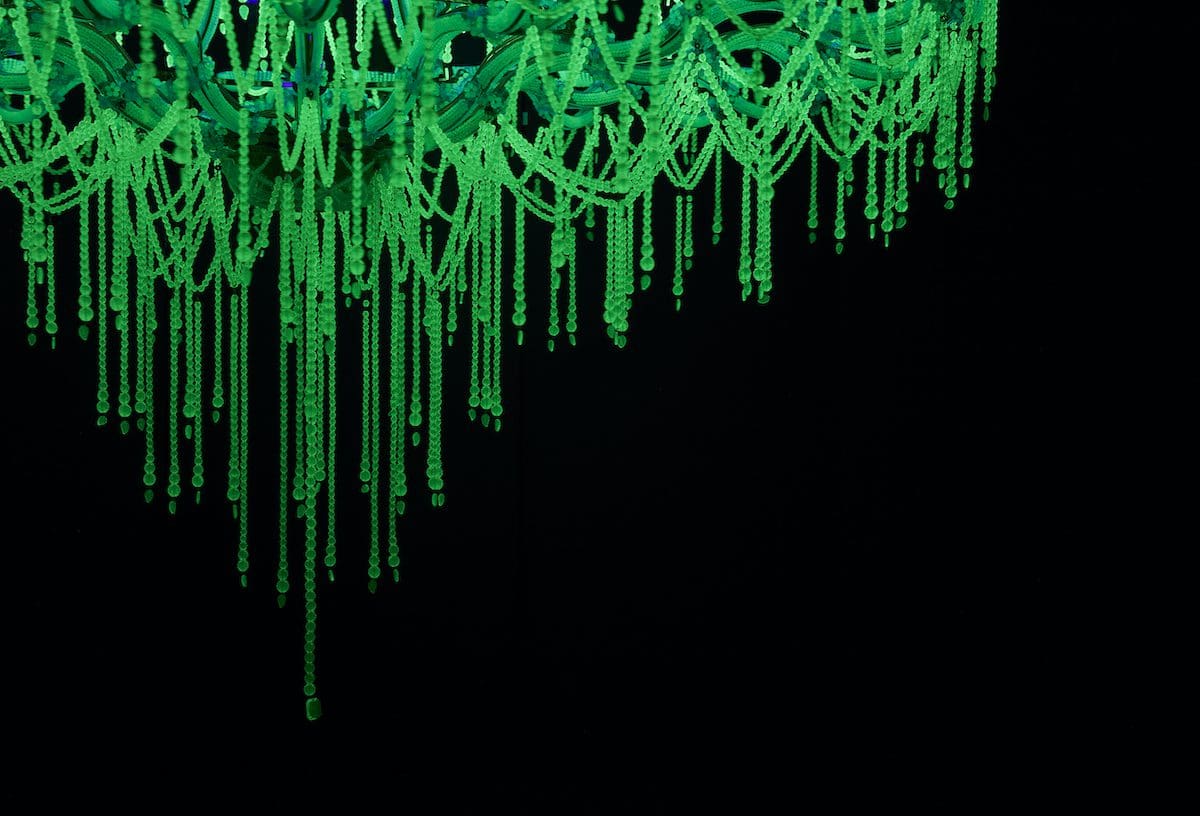

Ronan Sulich: Hanging Basket Wall Ornament by Peter Griffith

This everlasting basket of blooms, made by Sydney Technical College blacksmith Peter Griffiths around 1893, takes the wrought-iron skills of the old world and translates them to (what was then) a more modern idiom. It was not only created to show his skills, but also with the more practical purpose to hold newfangled electric incandescent light bulbs.

The design of the basket derives from 18th and 19th century and the flowers are a mixed bouquet of English roses, thistles and shamrocks combined with Australian natives: flannel flowers, waratahs and banksias. Indicative of a modern interest in the decorative form, it is also a nod to the growth of a national consciousness in the years before Federation. It was acquired the same year by the fledgling Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, which was conceived to exhibit and showcase the technical and decorative skills, from pottery, to carpentry, glass work and textiles.

Eva Czernis-Ryl: Satirical portrait bust of ‘Baron’ Schmiedel, hard-paste porcelain, Johann Joachim Kändler for Royal Saxon Porcelain Manufactory, Meissen, Germany, 1739

Found in Sydney in 1949 and thought to have been a garden ornament, this rare bust in early Meissen (German) porcelain is one of the most valuable objects in the Powerhouse collection.

A royal commission for a magnificent palace, it depicts Schmiedel as a jester at the court of the Polish Kings and Saxon Electors in Dresden. Immortalised in the form and material reserved for the upper echelon of society, Kändler portrays Schmiedel, the kings’ servant, foppishly dressed in the latest fashion and hung about with… mice.

Fabulously baroque in its theatricality, it was a joke at the expense of Augustus III’s witty and mischievous companion, famed for his morbid fear of rodents. Requiring unprecedented modelling skills and new technology to produce on such scale, the life-size bust belongs to the grand Age of Enlightenment story of the invention of European porcelain, a material so precious that it was known as white gold.

A holy grail of a 200-year quest to discover China’s secret porcelain formula, European true (hard-paste) porcelain was first made in 1709 by JF Bӧttger, king Augustus the Strong’s alchemist turned scientist. Meissen porcelain was a game-changing product: as Bӧttger’s porcelain formula spread across Europe inspiring others, it brought China’s global porcelain primacy to its end.

1001 Remarkable Objects

Powerhouse Ultimo

26 August—31 December