Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

HOTA, Home of The Arts, is pronounced “hotter”, which perfectly suits this gallery’s location, enjoying the Surfers Paradise climate. It also suits the calibre of artworks visitors are likely to experience there: having just re-opened, HOTA is not only championing diverse Australian artists, but will present significant international shows from the end of the year.

The old HOTA, opened in 1986 as the Gold Coast City Gallery and housed within the Gold Coast Arts Centre, had about 500 square metres of space. Now, in its own purpose-built building costing more than $60 million, HOTA has more than 8000 square metres to play with, making it the largest gallery outside an Australian capital. Director Tracy Cooper-Lavery has been working on no fewer than five separate new shows running concurrently for the opening—not to mention the commissioning of outdoor sculptural pieces by artists Judy Watson and Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran.

Cooper-Lavery spent some of her early curatorial career on the Gold Coast before taking up other regional gallery jobs, including at the highly respected Bendigo Art Gallery. Returning to head up HOTA in 2016, she has been impressed with the way the strong visual arts community on the Gold Coast and hinterland has sustained itself and strongly developed since she was there in the 1990s.

“After so many years in Bendigo and other places, coming back and seeing artists who have stayed and continued their careers here has been wonderful,” she says. “But there is also a whole new wave of artists who identify with the Gold Coast and are happy to make it their home and grow the creative culture here.”

Cooper-Lavery says the artistic bent of the Gold Coast runs in tandem with an inherited sensitivity to the region’s reputation, where locals continue to question “who we are as a community, and are we just about beaches and theme parks and holidays”. Evidently it’s more than that: the opening shows include Solid Gold, which presents “arts from paradise”, a collection of 19 locals with strong Gold Coast associations, and Hyperaware, taking in 20th-century art stars such as Ben Quilty, Nell and Sally Gabori. Other shows include World Upside Down in the children’s gallery, as well as other shows across three floors drawing on the 4400 works that have been amassing in the Gold Coast City Collection since the 1960s.

Cooper-Lavery is also working on international shows, developing relationships with big institutions such as London’s National Portrait Gallery, mindful of the uncertainty the pandemic has instilled around travelling exhibitions. That said, the Contemporary Masters from New York: Art from the Mugrabi Collection show is set to open in November. “Contemporary Masters will be exciting and a no-brainer to be the first international show, with artists such as Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Jeff Koons and Jean-Michel Basquiat—a lot of names people will recognise. We are ensuring that the exhibitions we develop are really accessible, as undoubtedly we are going to have a lot of new audiences to the gallery. People will go away thinking: ‘I never expected to see that here’.”

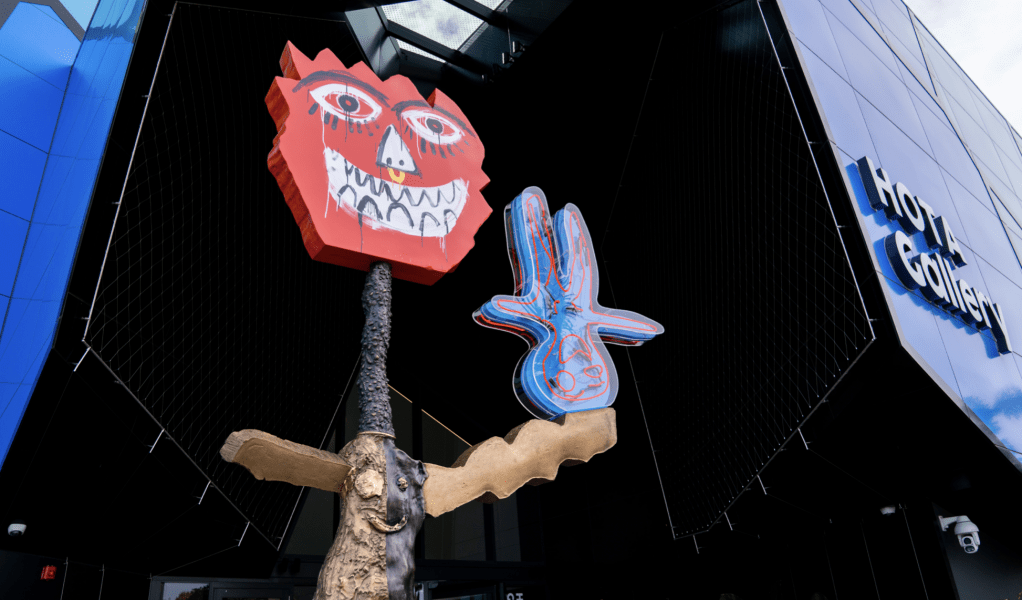

They’ll think the same about Nithiyendran’s new public art commission, a six-metre-tall sculpture installed at the HOTA entrance that consists of a surprising mix of materials: bronze, fibreglass, concrete and neon, with some of the bronze clearly cast from polystyrene. Nithiyendran describes Double-sided avatar with blue figure, 2021, as being like a guardian figure. While he is certainly used to working on a large scale, for this work the artist decided to toy with the use of materials, the idea of the monumental, and the way outdoor figurative sculptures are perceived, especially given that so many of them in Australian cities are invested with a traditional colonial history and a weight of murky meanings.

“Globally with public sculpture, people are thinking more about the framework of multiple, parallel or contested histories,” Nithiyendran says. “Something lots of artists and those interested in material culture have been scrutinising has been the representation of figures, and especially of idealised historical figures, in public spaces.”

Within an Australian context, as the artist says, the sculptures of old use their scale and monumentality to sanction certain values and histories “that aren’t so congruent with plurality and multiculturalism and what contemporary Australia stands for”. Nithiyendran upturns that with the use of his comic-book figurative work, and the way it embraces a smaller figure joyfully wrought in neon; its polystyrene textures and highly chromatic surfaces “make it look like a little model that has been upscaled”. As the artist says, “That’s where we can start being more imaginative with the types of sculpture we put in public spaces.”

These interests of Nithiyendran’s mesh wonderfully with the underlying intent of the re-imagined HOTA—to present the unexpected and the challenging in a way that both traditional and casual gallery visitors might not have envisaged experiencing on the Gold Coast. It’s not the place it used to be.

HOTA Gallery, Home of the Arts

From 8 May

This article was originally published in the May/June 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.