Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

The Indian Ocean Craft Triennial (IOTA21) is a new major craft festival, anchored in Perth, Western Australia. It extends over two focal exhibitions, satellite shows, a conference, talks and a fashion event at Boola Bardip WA Museum. For three months, some of the world’s finest craft practitioners and their work will muster in Perth and Fremantle. This congregation represents a profound concentration of craft skill and will undoubtedly catalyse a long-lasting wave of influence and connection in craft here and abroad.

The communality of craft is the great undercurrent of IOTA21. Behind each featured artist are their guilds, clubs, classes and groups; networks of knowledge, learning and togetherness. Craft traditions develop slowly, over lifetimes, making them inherently communal, as skills are taught, inherited, innovated and safeguarded beyond the horizon of any individual practitioner.

The IOTA21 artist cohort, therefore, is not drawn from any single guild, discipline or nation. Artists and artworks will travel from the rim of the Indian Ocean, formed by South Africa, Kenya, India, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Australia. “We are connected to each other across this country of the ocean,” says distinguished South African lacemaker Pierre Fouché, from his studio in Cape Town. “IOTA goes well beyond the idea of the global citizen (which can seem arbitrary or abstract) and offers this very natural way to bring people together across the water.”

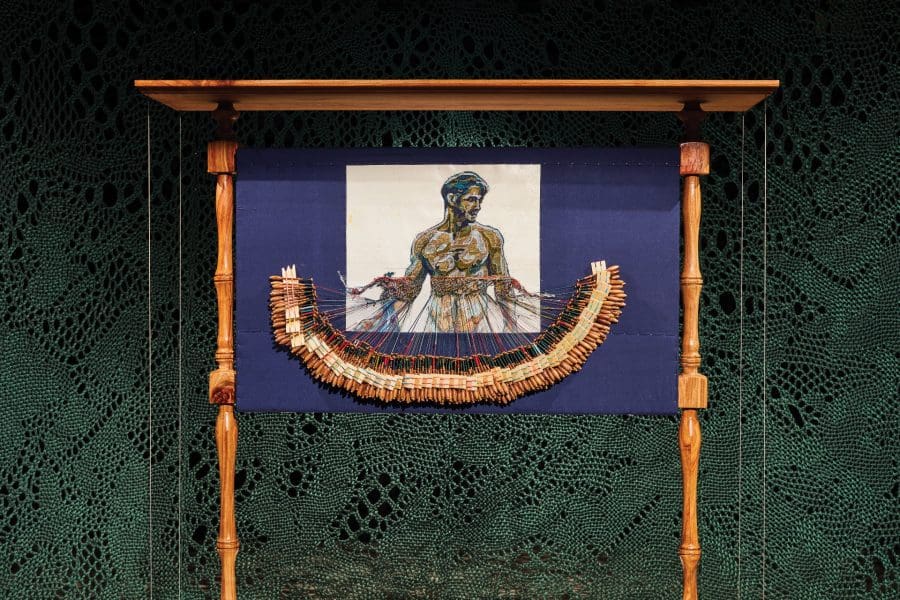

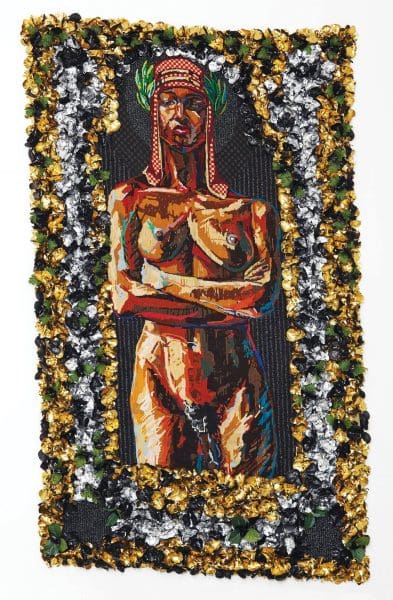

Fouché’s installation The Little Binche Peacock and Other Utopian Dreams will be erected under vivid spotlighting at John Curtin Gallery. The work is an august diorama. A three-by-eight metre panel of peacock-green binche lace forms a semicircle around “a shrine-like turned Kiaat-wood frame containing the emerging figure of a very classical, mythic nude, woven in silk floss bobbin lace”. The work has been exhibited twice since Fouché began it in 2017, and with each showing more of the figure emerges, as the artist ekes out centimetres of lace over weeks and months. Hundreds of bobbins hang in mid-tat, displayed with equal ceremony to the lace itself, merging work with artwork.

To the uninitiated, binche lacemaking is cacophonous and alchemic. Bobbins click past one another, swung by deft hands in speedy twists and turns. A chaotic phalanx of pins obscures the worksite from which the miraculously-cohesive lace emerges, either guided by a pattern or worked out algorithmically by the lacemaker. “Binche is notorious for its complexity,” says Fouché. “Lacemakers consider it the ultimate proof of skill.”

In coming to lacemaking, Fouché was well aware that he would be “entering and encroaching into a craft that has for generations been a safe space for women.” The artist was determined to demonstrate to the community, including the Cape Lace Guild, that his interest wasn’t touristic; that he would begin humbly and pursue excellence in good faith. His journey has been overseen for over a decade by Charlotte Keen, his “lacemaking mentor, best friend and someone who has come to embody the roles of the absent women in my life.”

Fouché layers his lace with other media: sensuous fragrance, lyrical titles and shadow-casting lights. The Little Binche Peacock radiates a complex scent which the artist designed after quitting tobacco and regaining the clarity of his olfactory and gustatory senses. The top notes recall Fouché’s childhood in Cullinan, a small town outside Pretoria, roaming in an “abandoned lot overgrown with khakibush, a weed introduced by British colonists. It smells powerfully floral, yet slightly rancid.” The fragrance imparts the complex politics and remembrance of a land bearing the marks of Imperialism. The final perfumatory puzzle piece came to Fouché in a vaporous cup of Lapsang Souchong. “The tea is noted for its smokiness. I realised what was missing: fire. The smoky base notes became an emblem for a greater narrative of a phoenix-like cycle of dystopia and utopia.”

The apocalyptic terms of this image are echoed in the subtitles for each part of the installation, which the artist drew from Song 177, a Dutch Reformed Church hymnal learned in childhood: “The Seas and All will Part, Expire; The Lord Himself among us.” The intensity of this language matches the in-person experience of the towering lace, casting a “filigree shadow that suggests being enveloped in deep water or thick forest”.

Juukan Tears by Western Australian jeweller Melissa Cameron delivers another immersive experience at John Curtin Gallery. Built using boldly scaled-up jewellery techniques, the installation responds directly to the May 2020 demolition of Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP) shelters in the Pilbara. “The site was drilled 382 times and blasted by Rio Tinto. The PKKP people were only given one week’s notice,” Cameron recounts. Juukan Tears condemns this cultural destruction and memorialises the shelters, a story the artist tells with symbolic repetition. 382 panels spell out “46,000-year-old Juukan shelters destroyed for… iron ore” in Morse code; a veil of 4,600 teardrop-shaped chains count the decades of continuous Juukan culture. “This place was a resource and refuge, a historic human site on the order of the Lascaux cave paintings or pyramids, yet those exploiting it didn’t have a full appreciation of that. We cannot let go so easily.”

Salvaged corrugated iron was flattened and submitted to an intensive shaping process, drawing on Cameron’s metalsmithing and interior architecture experience. “I had to saw and saw and saw,” she describes. “The pieces would mount up and then I’d take them to the drill press. It was a five-month process, which is a remarkably long project for a jeweller.” At four metres, the installation is arresting and physical.

Cultural continuity is a prominent thread throughout IOTA21. “Craft is a deeply human activity,” explains Fouché. “Our earliest technologies involved woven textiles, carved wood and vessels formed from clay. We would not have survived the ice age if we didn’t learn how to sew garments and shelters. Sewing saved humanity.”

With IOTA21, the common bedrock of craft becomes visible. Whatever their discipline, practitioners must assume a similar state of focus. “It wasn’t until I started yoga that I realised that in making lace I was practising a kind of meditation,” says Fouché. “Though protracted and repetitious, this work is far from mindless. You get into a rhythm, a haptic form of making, which is interspersed with puzzles and problems that you have to work out with careful attention. You can’t switch on the TV and go into autopilot.” Slowness, complexity and concentration coalesce together into a mindset impervious to fatigue and distraction. In fact, “the challenge is what makes it sustainable,” says Fouché.

This state of manual deliberation is part of what gives the art and craft worlds their mutual intelligibility. Division or grouping of the two is usually a matter of happenstance. Over seven years, the object and jewellery biennial Radiant Pavilion (September this year) has pioneered a strong working relationship between craftspeople and Melbourne contemporary art galleries, publications and symposia. This approach not only consolidates the role of craft as a key driver of contemporary art, but broadens the scope of what contemporary art curators, writers and historians engage with when measuring and reflecting Australian culture.

Just weeks later, Craft Victoria will host their month-long festival Craft Contemporary. Saving a handful of satellite events, the heart of the festival beats online, with virtual exhibitions, studio tours, residencies and interviews. This approach is not simply lockdown-proofing or contingency documentation. Quality photography and video means that the artworks and talks really sing online, enabling a lasting relevance beyond the festival dates and Australian context.

Also in October, the Greater Sydney craft sector will erupt with the fifth annual Sydney Craft Week. Led by the Australian Design Centre, the festival has an all-in atmosphere, with a profusion of markets, workshops, demonstrations and open studios geared to put amateurs, masters and patrons all in the same conversation. Its annual growth highlights a rising public sense of the relevance of craft to everyone, regardless of experience.

That so many craft practitioners and organisations are drawing together in the shadow of the pandemic reflects a renaissance in cultural reasoning. After a year of distance from others, that which is made by hand, slowly, with skill and expression has become of urgent interest and importance. We have remembered the profound humanity of craft and the craft object. “The last year has prompted such change,” Fouché reflects. “People have quit their jobs, got divorced, moved away, returned home, launched new initiatives. People have been reprioritising. Community and craft have found their way to the top of that list. The idea that lacemaking or any other craft is dying is a myth.”

Makers are reaching out for collaboration and community in Australia and across the sea. “It’s funny,” says Cameron, of the peers she’s met virtually in the lead-up to IOTA21; “we could so easily have sought these connections before the pandemic. Now we have a heightened awareness that relationships can be kept fresh and close despite great distance.”

The beauty is that it all counts. Friendships formed online are still friendships; craft and knowledge cross the Indian Ocean; and that watery passage lies open still, in wait.

Indian Ocean Craft Triennial

John Curtin Gallery, Fremantle Arts Centre & other venues (WA)

September—November 2021

www.indianoceancrafttriennial.com

This event is currently proceeding, however it is recommended you check the gallery website and local COVID-19 restrictions prior to visiting.

Radiant Pavilion

Melbourne venues and online

4 September—12 September 2021

www.radiantpavilion.com.au

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the Radiant Pavilion program will proceed online. Please check the Radiant Pavilion website for the most up to date information.

Craft Contemporary

Melbourne venues and online

1 October—31 October 2021

www.craft.org.au/craftcontemporary

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the Craft Contemporary program will proceed online. Please check the Craft Contemporary website for the most up to date information.

Sydney Craft Week

Sydney venues and online

8 October—17 October 2021

www.sydneycraftweek.com

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the Sydney Craft Week program will proceed online. Please check the Sydney Craft Week website for the most up to date information.

This article was originally published in the September/October print edition of Art Guide Australia.